“I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy,” wrote America’s second president, John Adams who was arguably of the view that the blood and toil of older generations should result in the freedom and actualisation of generations to come.

Sunday View with Tau Tawengwa

Closer home, while the older generation fought a protracted war against colonialism that resulted in the country’s independence, the “born frees” have not significantly experienced economic actualisation. as it stands, the Zimbabwean economy is struggling, and about 80% of the country’s adult population is currently unemployed. While various analysts and commentators have pointed to perceived reasons for the country’s economic quandary and the possible solutions thereof, of interest to me is the proposition to make the country’s labour laws more flexible in order to accentuate economic growth.

As part of his December 2013 national budget statement, Finance minister Patrick Chinamasa stated that government would review the country’s labour laws in an attempt to create a flexible labour market, which should see an increase in productivity.

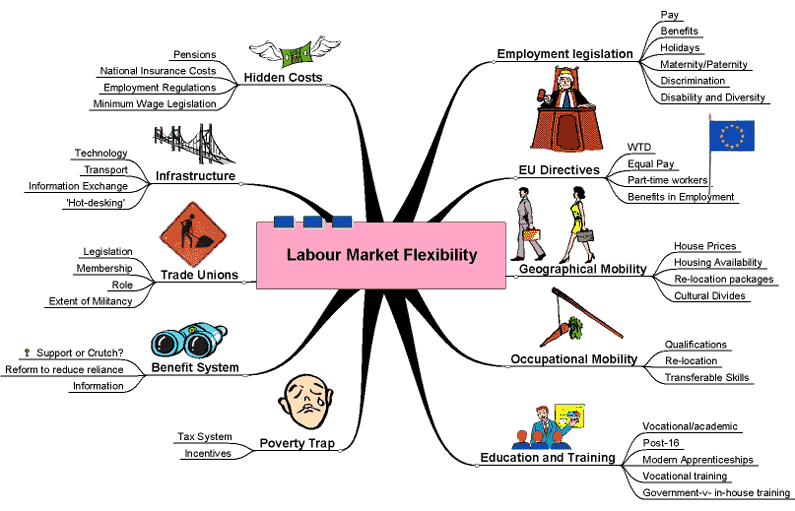

Put plainly, labour market flexibility makes it easier for companies to hire and fire employees and to alter work hours and wage rates. A labour market with low flexibility is characterised by rules and regulations such as minimum wage restrictions and requirements from trade unions as is the case in South Africa.

Now, it has emerged that cabinet recently agreed to amend the Labour Act in an attempt to loosen constraints in terms of retrenchments, terminal benefits, working hours and the arbitral awards system. This has apparently incensed the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) which is threatening to “go back to the streets” if this position is not reconsidered.

However, given the prevailing economic environment, one wonders whether militancy will in anyway assist the workers. After all, whether or not the government relaxes labour laws, retrenchments are ongoing.

In this light, it is important for the ZCTU to consider the following factors:

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Firstly, labour market flexibility will allow firms to become more competitive. It should be acknowledged that Zimbabwe does not exist in a vacuum, but is part of a globalised world. As it stands, the country has become a market for international products particularly from China, India and South Africa, and this has contributed to company closures. This is because our local products are too expensive and consequently uncompetitive.

In fact, research reveals that China has experienced massive manufacturing growth over the years because of (among other things) labour market flexibility. The fact is that frigid labour laws do not allow for large-scale employment in sectors that are labour intensive.

Secondly, The ZCTU needs to understand that its threat to “go back to the streets” is laughable, given that at best, it represents 20% of the economically active population. Unions are potent in highly productive economies like South Africa. Currently in Zimbabwe, those who are working are outnumbered four to one by those who are not formally employed, meaning that threatening militancy will only put the jobs of those who are formally employed in jeopardy.

Finally, while calls for a Poverty Datum Line (PDL) aligned minimum wage of US$540/month are noble, they are also impractical. You cannot force employers to pay amounts that they cannot afford — this will only lead to more retrenchments.

However, while labour market flexibility is favourable, it should be accompanied by efficient service delivery and good economic governance.

Tau Tawengwa is a researcher. He can be contacted at [email protected]