Early August 2014, a Johannesburg Stock Exchange-listed and South Africa’s largest micro-lender, African Bank (“Abil”), was placed under curatorship by the central bank of SA.

In the Money with Nesbert Ruwo

This followed a report on widespread credit losses that threatened the bank’s capital adequacy. Abil’s share price plummeted 61% when it published its quarterly operational review on August 6 2014 showing massive losses and an extremely high level of non-performing loans (NPLs).

The group reported that it was expecting a full year (to September 2014) headline loss of at least R6,4 billion (approximately US$640 million) compared to a profit of R365 million generated in the previous year.

The banking unit is reported to be expecting an NPL level of 31,7%.

The trading statement and a proposed recapitalisation call of at least R8,5 billion spooked investors who supported the business with R5,5 billion in a November 2013 rights issue. The group was bleeding cash despite management assuring the market that the worst was over.

The share price shed off 95% of its value from R6,88 at close of business on August 5 to 31 on August 8 2014. Almost R10 billion in the lender’s market capitalisation was lost in three days!

The South African Reserve Bank (Sarb) moved swiftly and placed Abil under curatorship on August 10 and “decided to implement a number of support measures” to “further strengthen the resilience of the banking system as a whole”.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The problems at Abil were centred on rapid credit growth, impairment and provisioning policy and a poor performing furniture business (Ellerines Holdings).

Abil is the only SA bank exposed directly to a furniture business. Abil has been trying to dispose of the perennial loss maker Ellerines with no takers in sight.

The curatorship programme will involve restructuring the business of Abil — separation of the good and bad assets.

Sarb will purchase the substantial portion of the “bad book” which has a book value of R17 billion for R7 billion and the “good book”, with a value of R26 billion, will be recapitalised for R10 billion underwritten by a consortium of SA banks (Absa, FirstRand, Investec, Nedbank and Standard Bank) and the Public Investment Corporation.

The cost to investors depends on the type of investor. Senior debt providers and wholesale funders will stomach a “haircut” of 10% estimated at about R5 billion, while equity-holders effectively lost all value when the business was suspended on the JSE.

However, the equity holders will be afforded “the opportunity to participate in the good bank”, obviously at a price of investing more cash into the business.

Closer home, the Zimbabwean banking sector has been experiencing weaker collections as borrowers fall under financial distress.

RBZ notes that NPLs have been rising since June 2009 when it recorded an NPL level of 1,62% to the current level of 18,5%.

The NPLs are expected to worsen as long as the economic fundamentals remain under pressure. The rising NPLs can be attributable to specific institution weak risk and lending management systems, borrowers funding mismatch i.e. borrowing short for long term assets, and weaker economic fundamentals.

NPLs do affect the profitability and erode banks’ capital and thereby limit their lending capacity and this would have a negative multiplier effect to the whole economy.

As a consequence of institution-specific factors and a tough economic environment, four Zimbabwe banks (Metbank, Allied Bank, AfrAsia and Tetrad) were in distress as of July 2014, reports the RBZ in its July 2014 Monetary Policy Statement.

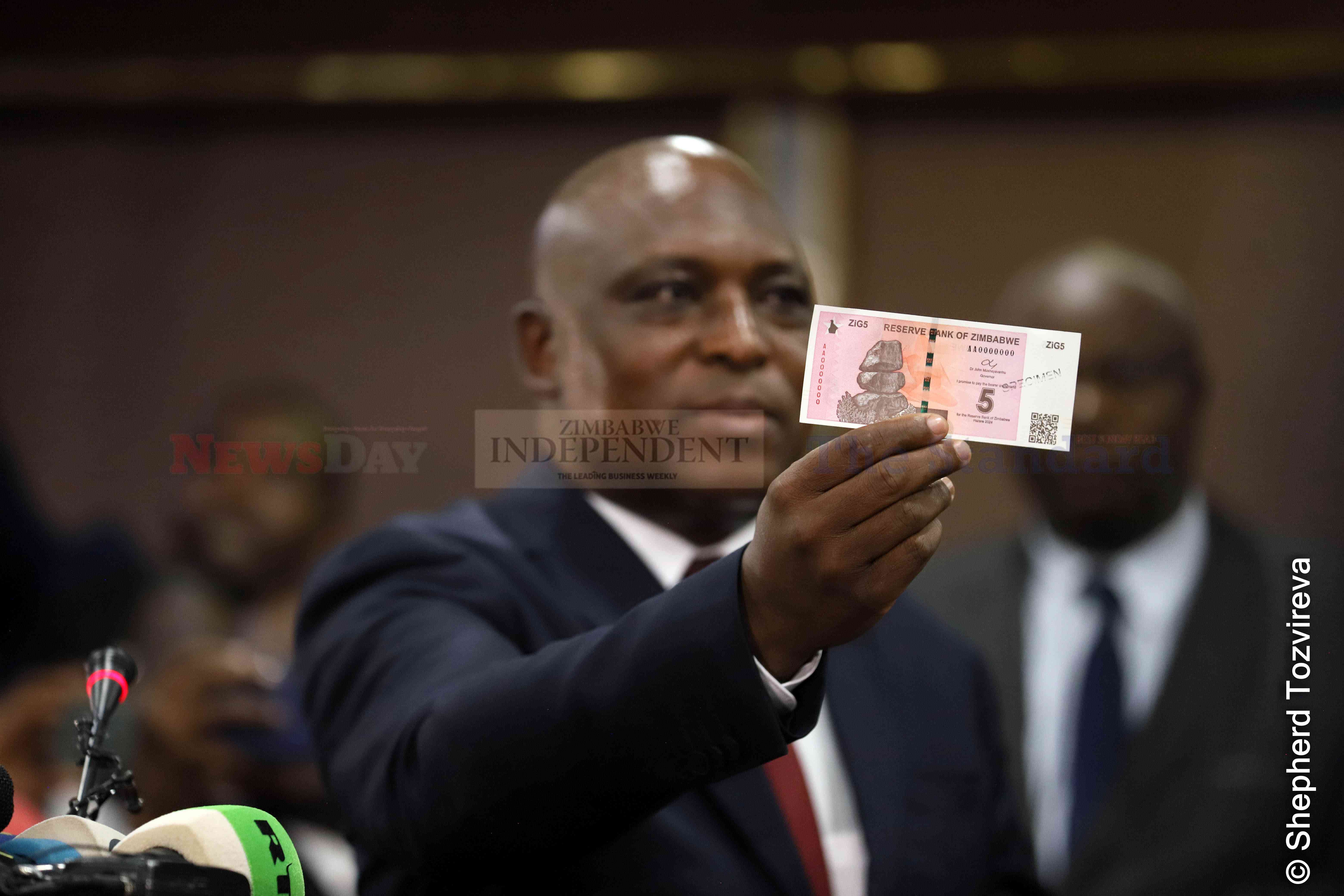

In response to the high level of NPLs, RBZ will establish a special purpose vehicle (SPV), Zimbabwe Asset Management Corporation (Pvt) Ltd (Zamco) to buy “bad books” from Zimbabwean banks, leaving the banks with “good books” and fresh capital.

This is with a view to support credit extension growth. Up until August 15, US$45 million of NPLs had been bought by Zamco.

Unless the fundamental governance and risk management systems are strengthened at the lending institution level, there is risk that incidence of NPLs will not be mitigated. In the case of Abil, the curator will be responsible for the transformation of the business model to ensure its going concern.

On the other hand, failure to collect or enforce on the “bad books” bought by the central banks-sponsored SPV will result in the central banks and other SPV investors losing capital. Loss of capital “invested” by a central bank in an SPV implies that the loss will be borne by everyone.

On September 2, Sarb appointed a Commissioner to probe alleged negligent and reckless lending and questionable management practices at Abil.

If Abil acted recklessly and negligently in its lending, this might bring into question the enforceability of the “bad book” bought by Sarb.

So when banks’ lending books become bad (mainly due to weak lending and risk management polices at an institution level), everyone pays the price. The investors (both equity and debt) do get “haircuts”, so does everyone as the central banks have (as highlighted in the cases in this article) to carry the “bad books”.

But should everyone pay for the sins of the few for the greater good?

[Using a ZAR/US$ exchange rate of R10]

Nesbert Ruwo is Zimbabwean-born investment banker based in South Africa. He can be contacted on [email protected]