I was born three years after Zimbabwe’s independence. Unfortunately, I have known only one president in my lifetime, and he has been a major failure. And his name is Robert Mugabe. This is a man who has presided over the ruination of the dreams of Zimbabwe’s young generation. According to the 2012 census, more than 65% of the country’s population is under the age of 35.

Literary Forum By Bookworm

The myth of Mugabe the “Great Leader” has been oversold to us. It is important to quarry deep our history to ascertain its origins. I have just been re-reading Mugabe, a small biography of the man published in 1981. This book is just as problematic as it is informative. Written by David Smith and Colin Simpson, it is more of feel-good propaganda. It was a portrait of Mugabe, then seen as one of the most able leaders on the African continent. There is too much drooling and idolising that happens in this book.

Since 2000, there are many books that have been written about Mugabe, all of them with the same tenor and mostly penned by aggrieved white authors who see a monster who persecuted their kith and kin. I wish I could disprove this conception and state my admiration for Mugabe, but I cannot, and will probably never. The tragic reality is that it will take my generation, the born-frees, our lifetimes to undo the damage that Mugabe and his generation have created.

Who is Mugabe? I have fleeting memories of Mugabe coming to a neighbourhood where we once lived when I was a child. His mother’s sister lived in our street. The president would come discreetly. Sometimes we happened to be playing chikweshe (soccer) on the street, and then we would be forced to stop, as unmarked cars with armed soldiers parked along our dead-end street. Before he left, we would be shepherded near his car and he would wave to a group of us, smiling, dusty, shoeless, gape-toothed boys calling ourselves “Peter Ndlovu” or “Ian Wright.” This image is common for most of these strongmen, to show they are in touch with the grassroots.

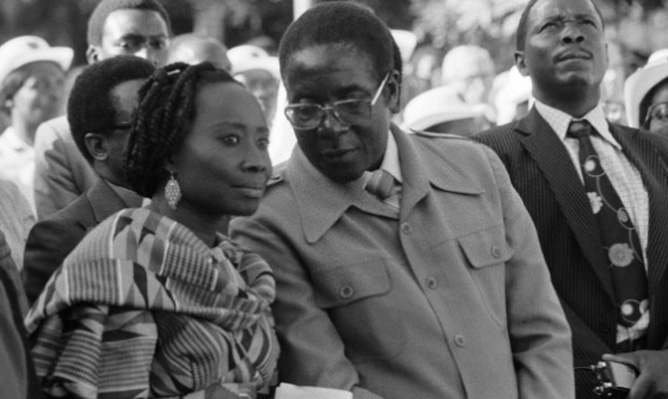

The opening scene of Smith and Simpson’s book has a young Mugabe saying, “When I am a man, I will be a teacher if I can.” The year was 1938. Mugabe graduated at Fort Hare University before a teaching stint in Zimbabwe, and then later in Zambia and Ghana. When he eventually joined the nationalist movement, he was a worldly man and married to a Ghanaian beauty, Sally Hayfron.

Sally was pregnant twice, and both ended tragically. First with their son Nhamodzenyika, who died as a baby from cerebral malaria, and later a miscarriage. In a cruel move, the Smith government refused to grant him leave from prison to go and bury his son.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Mugabe eventually assumed effective leadership of Zanu PF in 1976 after a mutiny against the leadership of Ndabaningi Sithole, founding president of the party. The party was then bitterly divided along tribal lines — Zezurus, Karangas, Manyikas and others — and whose feuding still provides part of the dynamics of party politics today. These feuds were masterfully critiqued, in Masipula Sithole’s seminal work, Struggles within the Struggles, a book whose essence has proved timeless considering the current state of our politics.

So it was that in 1980 a 56-year-old Mugabe, who used to be known for his trademark safari suits, had the air of a headmaster presiding over a class of young leaders who were supposed to learn from his great example and soon take over from him. That is how “Mandela the great leader” will always be an antithesis of “Mugabe the despot.” Mugabe became Zimbabwe’s first Prime Minister and from day one of assuming office, he moved to neutralise opposition from within his own party and outside his party from both the Ndebele and the residual white minority that had decided to stay.

Known to be decisive, cunning, and manipulative, Mugabe manouvred himself into a position of virtually unassailable power. When some of his comrades openly challenged him, they were demoted from government, and the unlucky ones, died in freaky car accidents and were buried with pomp and fare at the Heroes Acre with Mugabe eulogising them.

The book gives you a sense that a younger Mugabe was intellectually and academically a man of strong moral fibre who had a disciplined sense of purpose. The late Guy Clifton-Brock remembered him this way, “I was surprised at just how articulate he was, and how widely read. He neither drank nor smoked, in fact he could be a bit of a cold fish at times. But beneath it all there was an extraordinary young man, almost reluctant to emerge from beneath his self-imposed shell. He had this wide range of interests, he could talk about Elvis Presley or Bing Crosby as easily as politics. Above all, he had an overwhelming thirst for knowledge.”

For a generation of us, this is not the Mugabe we have got to know. We know of an irrational man, vindictive, cunning and authoritarian. Why has the old Mugabe negated the goodwill of the young Mugabe?

lFeedback: [email protected]