Prolific writer Christopher Mlalazi has a new book out. The novel, Running With Mother (2012) published by Weaver Press is not yet available in Zimbabwe but European readers can already buy it from the Oxford-based Africa Books Collectives.

Report by Tinashe Mushakavanhu

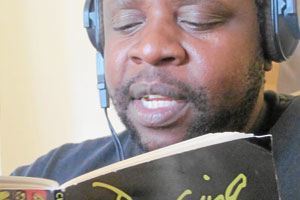

An e-version of the book is set to be released shortly as well. Mlalazi, who has published two other books — Dancing With Life (2008) and Many Rivers (2010) — is currently a fellow at the University of Iowa’s famous International Writing Project.

The new novel is being described as “unsentimental and unselfpitying” and focuses on the trauma of a family after surviving the Gukurahundi killings by the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade.

According to the blurb of the book, it vivifies an account by Rudo, a 14-year-old school girl who observes the terrifying events that take place in her village. Running With Mother provides a gripping story of how Rudo, her mother, her aunt and her little cousin survive the onslaught. Shocking as the story that unfolds may be, it is balanced by the resilience, self-respect, and stoicism of the protagonists. What makes the story so poignant is the narrative voice and the innocence of the narrator whose views of the world are not blemished or corrupted by any political ideology.

Mlalazi’s novel is written with insight and humour, hallmarks of his other fiction. While reliving the Gukurahundi horrors may seem bleak, the book actually provides a salutary reminder that even in the worst of times; we can find the humanity in each other.

Gukurahundi remains an emotive subject in Zimbabwe, one that especially Zanu PF politicos have continuously tried to hush. Some of the perpetrators of these killings are believed to be part of the current political and military apparatus.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Gukurahundi remains unexplored in the terrain of Zimbabwean literature. It is not as if our writers cannot deal with difficult subjects as there is a lot of “war literature” that was inspired by the liberation struggle and its aftermaths. In fact, our writers have remained preoccupied with the theme of what Simon Gikandi calls the “colonial factor,” and the different forms in which it manifested itself and the neurosis it authorised.

Early Zimbabwean literature openly links fiction to the visible militant movements against colonial oppression. Good enough, our fiction validates the struggle for freedom. But here is the dishonesty of Zimbabwean writers. This big, incredible experience happened — not just to a few people, but to hundreds of thousands of people. Here, there was a plan: mass killings which the black government — the army, the police, the people who were there to protect life and property — brought against the people they were supposed to represent and protect. Not a single person has been punished. This is something quite terrifying. Yet Zimbabwean writers choose to write about everything else and pretend this never happened. Unfortunately, we cannot escape the impact of this thing.

What really happened was that there was a tussle for power; power struggles were built into the structure of the country, and those in power wanted to stay in power. The easiest and simplest way to retain power was to appeal to tribal sentiments. This is still the case today. Gukurahundi is a fundamental issue we should publicly talk about. We must make sure that the evil practices and abuses we complain about so much in Zimbabwean society are not allowed to take root.

There is need for us to confront the Frankenstein monster of our history — Gukurahundi. Not talking about it does not make it invisible. There is need to critically and creatively engage with the history and reality behind this postcolonial bloodbath that took place in our yard. While the political leadership is largely to blame, fictional writers are also implicated in this conspiracy. By their silence, writers in Zimbabwe endorse the status quo when they can be better positioned to provide constructive critiques and empowering images.