These days the bearer of bad news without notice is Facebook.

Book Worm

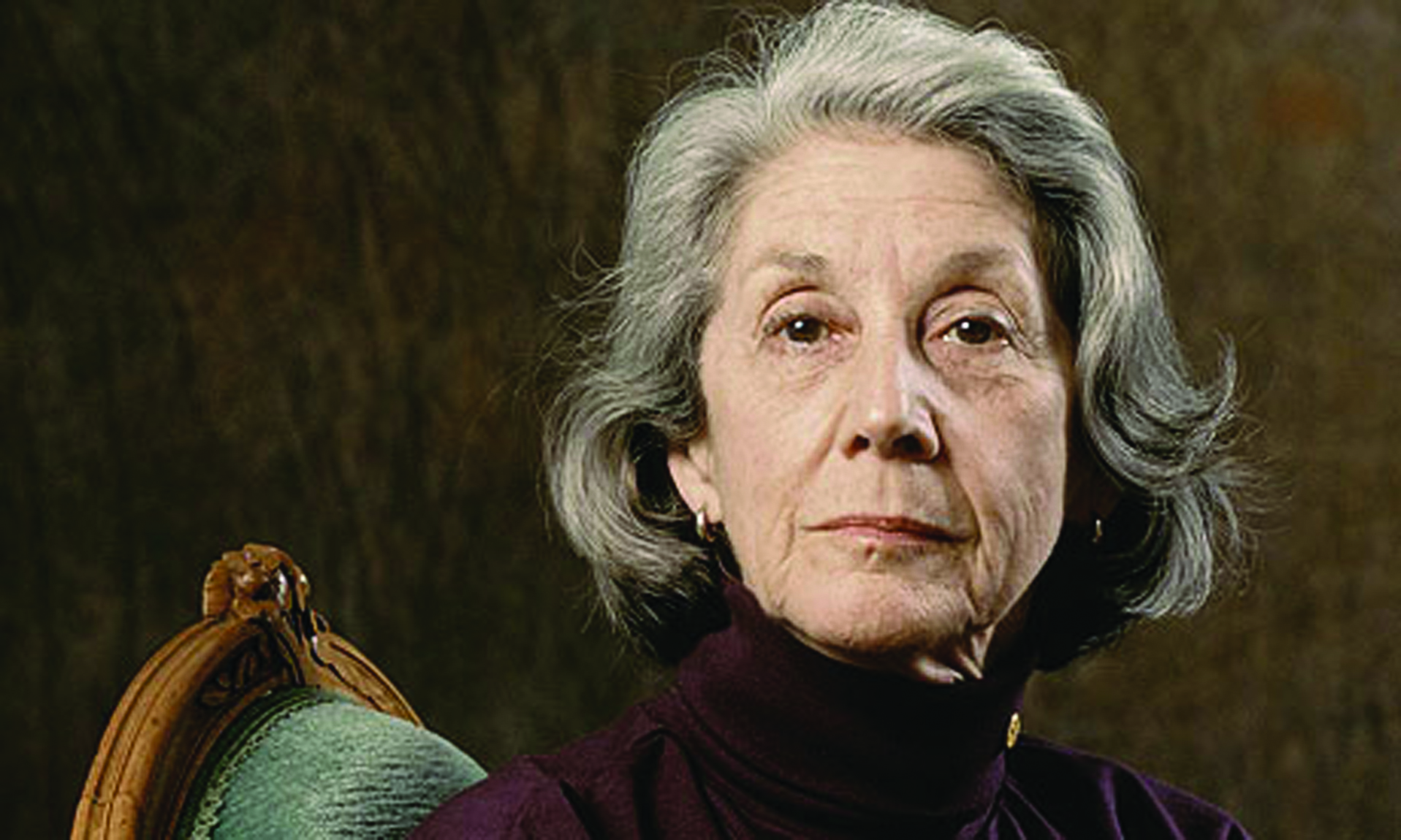

As most of my “friends” on the social network are writers or in the publishing world, people started randomly sharing pictures of Nadine Gordimer or some of her memorable quotes. Then I knew something was up. The announcement of the 15th Caine Prize was imminent in London. It is Okwiri Oduor from Kenya.

Since the beginning of her career in the 50s Gordimer’s early work had already started to chart out the territory she was to explore throughout her writing life: the intersection of the personal and the political, and the way in which individual lives are bent out of shape by external forces.

The issues of racial discrimination and freedom of expression were the most important ones for her. Her two grandest and most complex works, Burger’s Daughter and July’s People, were both written when she was deeply engaged in the anti-apartheid movement.

Both were banned by the apartheid government, as she expected they would be. It was her role as witness in the fight against the injustices of apartheid that resulted in her being awarded the Noble Prize for Literature in 1991.

Peter Florence of Hay Festival believes “it is important to set Nadine Gordimer in the context of Kafka and Camus, and the greatest literary pantheon in which she sits.” In interviews she revealed that books like E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle first opened her eyes to the “rigidly racist and inhibited colonial society” around her.

“Only many years later was I to realise that if I had been a child in that category – black – I might not have become a writer at all, since the library that made this possible for me was not open to any black child,” Gordimer said in her 1991 Nobel lecture. Though she attended the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, she didn’t graduate.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

It was at this point at which Gordimer began a lifelong affiliation with a cosmopolitan Johannesburg and this exposed her to the antiapartheid intellectuals and liberals living in the city. It is from this vantage position that Gordimer chronicled her country’s journey from apartheid to troubled democracy.

Though she remained confined within her white, middle-class, liberal environment, it was this restricted social sphere that would frame both the strengths and the weaknesses of her literary work, for her characters would consistently highlight the limitations and corruptions of white South Africa while remaining firmly within its boundaries.

Critics and scholars have described the whole of her work as constituting a social history as told through finely drawn portraits of the characters who peopled it. Gordimer was the author of more than two dozen works of fiction, including novels and collections of short stories in addition to personal and political essays and literary criticism.

Gordimer was never detained or persecuted for her work, though there were always risks to writing openly about the ruling repressive regime.

One reason may have been her ability to give voice to perspectives far from her own, like those of colonial nationalists who had created and thrived on the system of institutionalised oppression that was named the “grand apartheid” when it became law.

She never stopped grappling with politics, despite her disdain for the polemical. And book by book, she crept closer to reconciling her writing with her political self. What she did not want to do, she said in interviews, was to write in the service of the anti-apartheid movement, despite her deep contempt for the government system.

Over time, she revealed that she had been far from passive when politics touched her personally. During the apartheid era, she acted as a conduit and passed messages; hid friends, including high-ranking figures such as Albert Luthuli, who were trying to elude the police; and secretly drove others to the border. All these actions appear in her fiction, carried out by characters much braver than she portrayed herself to be. This made her a darling of the black political class.

That relationship was to change. She was too critical of the excesses of the post-apartheid leadership and their failure to uphold democratic values that benefitted ordinary South Africans. The ANC in a statement described Gordimer as “a giant” who fought for freedom in the country through her writings.

Her influence spread across to Zimbabwe, a country that Gordimer had first visited in the 1940s when she was a young girl. She was one of the African writers who came to support the birth of the Zimbabwe International Book Fair in 1983 at the National Gallery where it is reported she had a memorable event with Dambudzo Marechera. The other writers included Chinua Achebe, Gabriel Okara, Ingoapele Mandingoane, Jack Mapanje, Kristina Rungano, Nurrudin Farah, Lewis Nkosi, Marechera, Charles Mungoshi among others.

It was Gordimer who once remarked, Marechera stuck his neck out while others were reluctant to open their mouths. Indeed, with the recent political crisis in Zimbabwe, Marechera specifically helps us to remember that all that glittered in 1980 was not gold.

Warning lights flashed through his exuberant fiction; his challenging questions constantly provoked the authorities. Marechera’s writing blisters every totem pole. He took delight in satirizing the “chefs” of the post-liberation years.

In 1995, Gordimer was to make another appearance at the Book Fair. That particular edition has since been historicized for the controversies that ensued around the gay debate. The theme for that edition of the book fair was “Freedom of Expression.” President Mugabe delivered the opening speech of the book fair and chose the occasion to denounce gay rights in blistering terms. He made the now notorious remarks about gay people being “worse than pigs and dogs” and, without even a nod in the direction of Oscar Wilde’s trial, claimed that next they “would be doing it in the street.”

Gordimer disagreed with Mugabe’s remarks. She said, “I am appalled. It is very strange to be standing under the banner of Freedom of Expression while a group has been denied the very right to express themselves at the book fair… We are saying that human rights are universal rights, but it seems there is a double standard.” The issue of gay remains contentious in Zimbabwe, where it is currently outlawed.

Survived by two children from two marriages, Gordimer died at 90 after a short illness at her home in Johannesburg. Having written more than 20 books of fiction and non-fiction, her legacy will forever be deeply etched in our conscience.