The dramatic revocation of Ray Goba’s appointment as prosecutor general (PG) late last week betrays just how far the executive, aka the Zanu PF ruling elite, has captured the judiciary. The judiciary, clearly, is now a pawn in the party’s successionist and factionalised power politics.

By TAWANDA MAJONI

Goba is most likely to become the shortest serving chief public law officer in the history of the country. Misheck Sibanda, the chief secretary in the Office of the President and Cabinet (OPC), on Friday handed down an extraordinary general notice announcing the revocation of his appointment.

That was about a month and a half after Goba’s appointment on September 13 through the Government Gazette General Notice 493 of 2017. Goba replaced Johannes Tomana who was accused of abusing his office and had been subjected to a lengthy probe by a special tribunal.

You can’t miss the fine print of the notice that announced Goba’s appointment. Sibanda was explicit in the notice: “It is hereby notified that His Excellency, the President of the Republic of Zimbabwe, has appointed Ray Hamilton Goba as the prosecutor general with immediate effect.”

Then came the messy volte face through General Notice 692 last Friday: “It is hereby notified that the captioned General Notice (493 of 2017) that was published in the Gazette Extraordinary on September 13, 2017 is repealed”.

You can’t have a whole president of a country who is so fickle. This is not Zumaland where a Finance minister is hired and fired in the same breath. Granted, Goba was not sworn in as the new PG when President Robert Mugabe chose him out of the numerous candidates who had contested for the post. But that’s neither here nor there.

It’s not as if he refused to be sworn in. When the president makes an appointment that requires swearing in, it’s the OPC’s baby to ensure that due protocol is observed. That means the failure to swear Goba in was the OPC’s, and, in turn, Mugabe’s sinister omission. The new PG couldn’t move from office to office with a machete in his hand forcing people to swear him in.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The notice that revoked Goba’s appointment does not give reasons for the U-turn and it would be interesting to hear the OPC’s explanation of this untidy decision. Even if the president has the privileged power to repeal the notice of appointment, it would never wash to use the omission to swear him as a legit technicality to stand the PG down. As far as I am concerned, the most sensible thing to do would have been to advise Goba to suspend working as the substantive PG till he was sworn in.

But that this did not happen shows that there are underworld machinations within the executive arm of government. It would seem that Goba is a victim of the factional fights within Zanu PF as Mugabe waddles into the political sunset. To start with, he has been strongly linked to a Zanu PF faction, Lacoste, which Vice-President Emmerson Mnangagwa is alleged to lead.

Mnangagwa was in charge of the Justice ministry until the recent Cabinet reshuffle. Goba had been regarded as Mnangangwa’s protégé, just like Tomana. In August, Jonathan Moyo — Mnangagwa’s rival who is part of the Generation 40 outfit — sought to prove that the Lacoste leader had captured several key state institutions, the Justice ministry included. He seemed to have made his point well, much to the joy of the likes of Mugabe’s wife, Grace, who is fighting Mnangagwa from the same corner as Moyo, if not the president too.

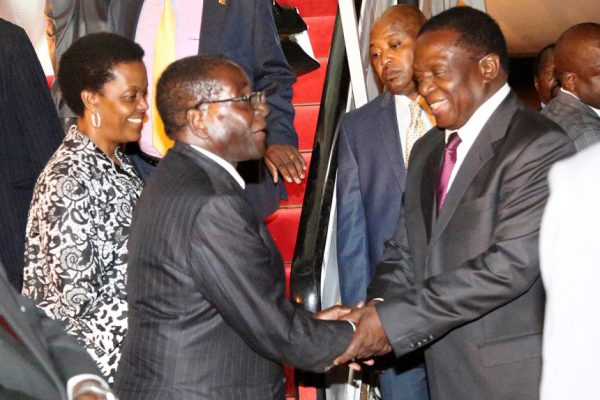

Clearly, Mnangagwa was growing in clout to position himself to take over from Mugabe. He seems to have courted the largely unspoken blessings of both the West and China. And, closer home, he enjoys the support of the military and war veterans — pretty powerful agencies as it were. Since harbouring an ambition to replace the immortal Mugabe is an unwritten crime and political sin, the president did not take lightly to that growing stature.

It would, therefore, make sense that Mnangagwa’s influence in the judiciary be curtailed. It was bad enough that Mugabe took the ministry away from his deputy and gave it to a political rival, Happyton Bonyongwe, the director general of the Central Intelligence Organisation. Bonyongwe’s new appointment was to both spite Mnangagwa and ensure that his influence was diluted.

The former spook boss seems to have enjoyed strong links with Joice Mujuru, Mnangagwa’s erstwhile factional rival who he helped eject from Zanu PF. Naturally, Bonyongwe would be a good buffer to Mnangagwa, toe to toe. And because he was gifted with the ministry, the former CIO director general is now beholden to Mugabe who, as already mentioned, is boiling inside that Mnangagwa wants his post.

In the same measure, Mnangagwa looked just too anxious to ensure that the judiciary was under his firm control. I don’t think it’s untrue that he had manoeuvred to ensure that Tomana was replaced by another of his proxies. Add to that, the fact that he was deeply mired in the controversy that surrounded the selection of the chief justice (CJ). As we are told, he had his own preferred candidate, but just as he has lost Goba, the CJ post went to a different person.

Why is this important to understand? The utility of the judiciary stretches beyond enabling that justice is delivered. In fact, the judiciary is sometimes critical to ensure that justice is not delivered, so as to protect certain interests. It is often used as a political tool because the law is hardly neutral. And this is where the issue of Zanu PF factionalism and successionism come in.

You will remember that, at the height of the fast track land redistribution programme, Mugabe shook the Supreme Court bench in a big way. White judges were removed en masse to make way for a politically correct black bench led by the now retired Godfrey Chidyausiku.

It would be difficult for the Zanu PF government to get favourable rulings where land takeovers were concerned. The fast track programme was conducted in an untidy way and there was need to sometimes make revolutionary and accelerated decisions. In other words, the black bench that was ushered in became a political vehicle to ensure that justice was defined and delivered the way the pro-land reform regime wanted.

This time around, the judiciary must be politically correct in so far as it must pander to the whims of respective successionists who want things to sway in their preferred direction. Firstly, the judiciary will be handy in managing court processes relating to Mugabe’s succession.

It is highly possible that a faction and its members who feel aggrieved will troop to the courts, the Constitutional Court in particular, to challenge certain decisions or developments. Already, war vets have expressed an intention to do so following the Cabinet reshuffle. Grace and G40 would need a Constitutional Court or Supreme Court that is pliant, just as Lacoste would wish the same.

Secondly, the courts will be handy to rig prosecution and litigation. I have already pointed out that courts are far from neutral and don’t necessarily deliver justice. The law, because it is there to be interpreted rather than enforced, is a subjective rather than objective phenomenon. That allows much room for manipulation. It thus becomes important to have in place law authorities that you can handle easily so that they can manipulate the law.

Most, if not all, the protagonists in the succession fights have cackling skeletons in their lockers. Over the decades, they have invariably looted state coffers, stolen properties, flouted tender procedures and grossly violated human rights.

Succession wars in Zanu PF are getting dirtier by the day because involved factions know that Mugabe’s end is nigh. So they must gain advantage by hook and crook. That includes abusing the justice system to undercut their rivals. All the fighters want to ensure that they stay away from the dock as far as possible. At the same time, their enemies must go to jail so that they strengthen their power foothold and keep safe.

This is where the likes of Goba come in. Or, more appropriately, get out. The National Prosecuting Authority determines whether or not cases go to court. Since G40, like Lacoste is not clean by any means, it must have a PG who is manipulable. One who will stop its members from being prosecuted and sent to jail and one that will be used to send its foes to the gallows if necessary.

l Tawanda Majoni is the national coordinator at Information for Development Trust (IDT) and can be contacted on [email protected].