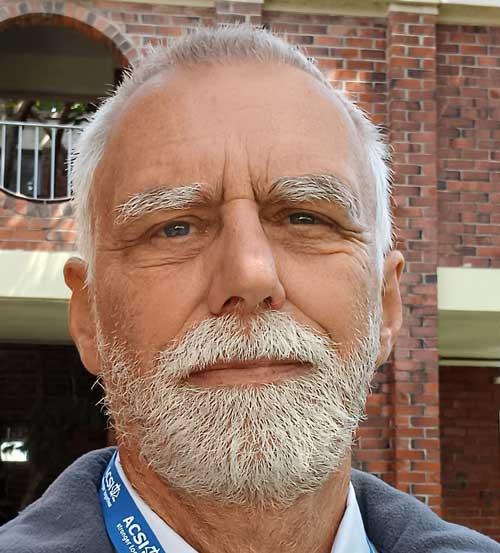

TRAIL-BLAZING former Zimbabwe cricket team fast bowler Henry Olonga has revealed how he felt betrayed by some of his fellow countrymen, who labelled him a “sell-out” in the wake of his black armband protest against former president Robert Mugabe’s policies 14 years ago.

BY DANIEL NHAKANISO

Olonga, the first black cricketer to represent Zimbabwe and former captain Andy Flower stunned cricket and the wider world after protesting the “death of democracy” in the country by wearing black armbands at the 2003 Cricket World Cup, which Zimbabwe co-hosted with South Africa.

Olonga’s decision to protest against Mugabe’s policies was triggered by the “farm invasions” targetting white farmers in the early 2000s, which saw violence and deaths across Zimbabwe.

Although the pair’s protest was hailed globally as one of the most courageous political statements ever made by sportspersons, locally although appreciated by many, they were made to pay the price for standing up for their principles.

While Flower had already announced his plans to retire from international cricket after the World Cup ahead of his swansong in English County cricket, for Olonga, who was just 26 years old at the time and in the prime of his career, there was nothing, other than uncertainty.

Olonga was forced off the national team and had to go into exile in England after receiving threatening emails, one of which said he was a “sell-out” and that he would be a “marked man” if he returned to Zimbabwe.

While he managed to get safe passage to England after his Zimbabwean passport expired in 2006, he could not leave the country for nine years, before finally getting his citizenship.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Looking back, Olonga, who is now based in Adelaide, Australia, said what hurt him the most was that the people who turned on him and called him a “sell-out” were those he was protesting for.

“I came from a middle-class family and I didn’t have to protest. I had a good life and I was earning foreign currency at a time when it was impossible to get it,” Olonga told The Indian Express from Australia where he settled down with his Australian wife Tara and two daughters in 2015.

“When I was protesting, I was thinking about the same people who later turned on me,” recalled Olonga, who has played 30 Tests and 50 ODIs.

“There was this indoctrinated youth militia called the Green Bombers. They would shave their heads and do the government’s bidding. They were all at the clubhouse jeering me the day I played the one match that I was allowed to play in Harare after the protest,” he said.

Over the years, Olonga has recounted his story to audiences around England, and now in Australia many times.

At times, he said, he does get bored with having to retell his story for the “10 000th time”, but added that it remains relevant.

“I was never a political activist. I dipped my toe in that world for 10 seconds and that’s all I get remembered for, as the man who protested against his president and lived to tell the tale,” he said.

Olonga’s song Our Zimbabwe became a regular feature on ZBC TV in the weeks leading up to Mugabe’s resignation last month. Calling for Zimbabweans to unite and stand up for their country, it became a kind of unofficial national anthem embraced by joyous Zimbabweans at the end of Mugabe’s 37-year rule.

It’s taken nearly 15 years, but Zimbabwe is listening to Olonga’s song again.

“I was pleasantly surprised to hear that the people of Zimbabwe have embraced the song and that ZBC has been playing it as events unfolded in Zimbabwe,” Olonga told The Associated Press in a separate interview from Australia. “It is very humbling for all of us involved.

“It stands as a challenge to each and every Zimbabwean to embrace their part in making a stand for their country. Judging by events that occurred recently, I think Zimbabweans are finding their voice and have done just that.”

Olonga, now 41, hasn’t set foot in Zimbabwe since he left in a hurry in 2003. It might finally be time to return.

“The true litmus test going forward is whether each Zimbabwean will heed the call and play their part,” he said. “I know I will if the opportunity arises.”