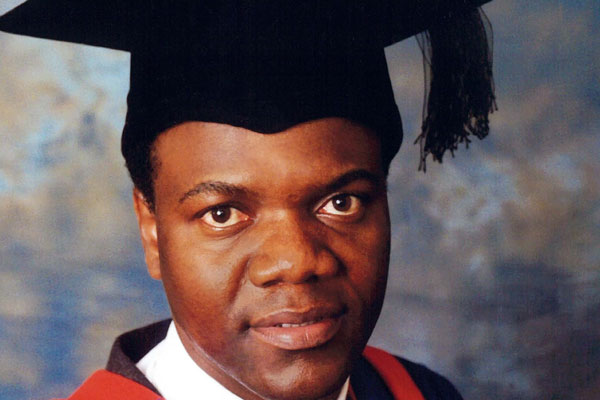

Reviewed by Gorden Moyo

Title: The Path to Power: In search of the Elusive Zimbabwean Dream, an Autobiography of Thought Leadership, Volume II Author: Mutambara Arthur Guseni Oliver Publisher: SAPES, Harare Number of pages: 544

Professor Arthur Mutambara presents us with a detailed and carefully crafted autobiographical narrative of his politics, political formation and political memoirs of the tumultuous years between 2003 and 2009. This anthology is a sequel to his Volume I, which at its publication in 2017 attracted the attention of a wide array of readerships, viewerships and social media warriors, including bloggers, Facebookers, Instagrammers, Podcasters, Twitters; and democracy campaigners in Zimbabwe as well as from across Africa, the UK and US.

If his Volume I was a pacesetter, then this Volume II is a trailblazer that deploys present tense registers as it unveils the life experiences and political makings of one of Zimbabwe’s erudite scholars, tactful politicians and thought leaders gifted with intellectual acuity for nuance and clarity of ideas.

I would be hard-pressed to name someone better fitted to pen down a balanced account of the political memories of the first decade of the 21st Century in Zimbabwe from a direct participant perspective than Mutambara. He was one of the interlocutors of both the Global Political Agreement (GPA) and the Government of National Unity (GNU) to which he became the deputy prime minister.

This anthology is a breezy read that brings together a dense panoply of facsimiles of sources including dozens of Mutambara’s fiery political speeches, newspaper articles, official party documents and detailed personal notes and a variety of carefully selected photographs, which collectively provide validity to the claims made in the anthology.

While the majority of the texts describe Mutambara’s personal views and experiences in various political and social settings and encounters, the anthology is a monumental piece of scholarship that warrants close reading by those interested in political economy, political history, negotiated political settlements, memorialisation and public diplomacy as well as geopolitics and geoeconomic governance.

Indeed this anthology is more than just an autobiography of an individual character called Mutambara.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

It is an historiography of Zimbabwe qua Africa written in a way that no other author (known to this reader) has done before.

For the sake of accessibility and readability, this anthology is arranged into three chronological sections. Section I chapters focus on Mutambara’s re-inscription into Africa and Zimbabwe’s political sphere after his sojourn in the global North for over a decade.

The chapters in this section also portray Mutambara’s family reunion and, more importantly, his rite of entry into the institution of marriage as well as his elevation to the apex of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) leadership.

Section II is probably the heart of this anthology. It discusses the brutality and impunity of Zanu PF under Robert Mugabe, the former president of Zimbabwe.

Section III provides the context, circumstances and issues surrounding the fateful 2008 elections.

The book concludes with theSadc-led mediation and the consummation of the GNU and Mutambara’s “moment” as the deputy prime minister of the Republic of Zimbabwe.

The “central nervous system” of this anthology is what Mutambara bills “Zimbabwean Dream”. The descriptors of “Zimbabwean Dream” include, among others, “peace, equality, stability, democracy, inclusive economic growth, and shared prosperity” (pp.xvii). This Mutambaran dream is neither unique to him nor to Zimbabwe, it is not universal either, it is pluriversal and purely global in perspective.

In fact, it has echoes of Martin Luther Junior’s “I Have A Dream” speech; Mahatma Gandhi’s “Dream for Humanity”; Desmond Tutu’s “God has a Dream” and Che Guevara’s “Africa’s Dream”. Regrettably, this dream project has proven difficult and elusive to attain in both Zimbabwe and Africa.

Mutambara lays the blame for its failure squarely on the doorsteps of political leadership. In particular, he decries Mugabe’s venal leadership as predisposed to primitive accumulation, suppression of dissent, epistemicide, linguicide, ethnicide and genocide as signified by the 2008 botched elections, Operation Murambatsvina of 2005 and the Gukurahundi of the 1980s.

Along the way, the book deconstructs a number of misconceptions, half-truths and alternative truths, disinformation and distortions about Mutambara’s political role and place in history and society.

The book deploys some documentary evidence and copious quotations as antidotes to falsehoods in order to set the record straight.

First, the book dismisses the misconception that Mutambara was parachuted to MDC leadership without a history of challenging Zanu PF.

The book presents some historical developments, political events, social memories and life experiences that shaped Mutambara’s political making and politics well before the formation of the MDC in 1999 and its split in 2005.

For instance, the book reminds the reader that Mutambara led the student movement against the Mugabe regime at the tail-end of the 1980s, that is, long before the MDC was conceived.

Indeed the chronicles of the book demonstrate that Mutambara’s political making was not an act of benevolence from any individuals; it was not contingent to any particular political formation. Instead, it pre-dated the political events of 2003 to 2009.

Second, the book expunges the myths and fictions that attribute the split of the MDC in 2005 to Mutambara.

the evidence provided in the book indicates that Mutambara only became a key MDC leader well after the split, and that he was not involved at all during the chaotic split of that party.

If anything, as opined by the book, Mutambara more than any other party leader consistently pushed for the reunification of the two formations of the MDC.

Instead, the book attributes the failure of unification efforts to the intransigence of the MDC-T leadership, which reneged on the agreement that was reached by the two parties.

Moreover, the book reveals that Mutambara never intended to challenge Tsvangirai’s leadership in the event of the unity of the two formations of MDC.

To support this claim, the book points to the fact that Mutambara was not a presidential candidate for the 2008 elections. The book claims that he deferred to Simba Makoni after the MDC electoral pact failed.

Third, the book also repudiates some spurious allegations that once Mutambara assumed the MDC leadership, he was not vocal against Mugabe and his Zanu PF associates.

His critics argued then that Mutambara had acquiesced and became a Mugabe ally. On the contrary, the book presents him as the most strident political leader in his attacks not just on Mugabe, but the entire ecosystem of the Euro-North American powers.

Mutambara was also vocal against the Chinese and other emerging economies of the global South that were looting Zimbabwe’s mineral wealth at the time.

Thus, unlike most opposition leaders who singled out Mugabe’s person as the problem in Zimbabwe, Mutambara’s fiery speeches pointedly aimed at neoliberalism, global capitalism, narrow radical economic nationalism, primitive accumulation, cronyism, corruption, democratic centralism and lack of constitutionalism as the real problems that needed attention from the opposition rather than a reductionist approach of targeting just an individual.

Not surprisingly, this approach earned him all sorts of names from some Zanu PF publicists and some MDC-T enthusiasts, hence his tenuous relationship with Tsvangirai and MDC-T (pp.192).

In short, the chronicles in this book are tactically presented to banish and unmask all kinds of mendacities and hypocrisies that maliciously and deliberately attempted to distort Mutambara’s place both in history and society.

At the same time the book reveals some startling insights about the GPA negotiations. On the one hand, the book highlights the role played by the Euro-North American powers, in particular the US, EU, and the UK who behind the scenes attempted to use their soft power to push for their preferred outcome of the political negotiations between MDC, MDC-T and Zanu PF.

However, the book does not provide details of the nature and scope of these geostrategic manoeuvrings.

On the other hand, the book provides a detailed discussion on the credibility of the former president of South Africa Thabo Mbeki as the facilitator of the political negotiations in Zimbabwe.

It notes that there were allegations that Mbeki was a dishonest broker of the GPA negotiations and particularly his quiet diplomacy was viewed with suspicion.

Mbeki’s critics claimed that he used all sorts of subtleties and subterfuge ways to privilege Zanu PF, including providing written political advice to Mugabe.

This anthology explains why these critics were probably justified by referring to a document said to have been authored by Mbeki.

The document provides evidence of Mbeki’s disdain for the opposition in general and pathological hatred for Tsvangirai in particular (pp. 232-233).

While drawing lessons from his political involvement during this period, Mutambara also diverges into the epochal periods outside the 2003 to 2009 framework.

This is unavoidable because of the dramatic removal of Mugabe from power in November 2017 and the subsequent elections of July 2018, which were won by Zanu PF.

The book provides a thorough, comprehensive, insightful and no-holds-barred treatment of the 2018 elections.

In the process it raises a battery of questions, which are screaming for answers from the opposition (pp.411-412).

In response, the author outlines his views on what will constitute a viable path to power for the opposition in Zimbabwe; and delves into the vision and strategy that he believes will propel the country towards inclusive growth, inclusive development and inclusive society.

To this extent, the book is an open invitation to Zimbabweans and Africans to embrace thought leadership, which connotes a leadership orientation that is underpinned by unconventional ideology, which is historically nuanced, culturally sensitive, influentially and contextually grounded.

Mutambara believes that thought leadership is a key transformative vector, which is essential for Africa to avoid being bypassed by the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Additionally, this anthology overflows with contemporary issues including global challenges such as climate justice, massive migration, international terrorism, biopiracy, Brexit, the rise of the Southern economies such as China as well as the dramas of Donald Trump and his fantasies of deglobalisation, rise of new nationalism and patriotism.

While noting the possible impact of these global developments on Africa, this anthology canvasses for multilateral diplomacy and regional integration as solutions to continental and global problems.

Hence, the book celebrates the signing of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) on March 21, 2018 in Kigali.

Mutambara believes that the AfCFTA will immensely contribute towards the realisation of the African Dream and African Vision 2063.

From my perspective, there are only three minor points to criticise about the book.

First, although the author does an impressive job of discussing the actions and motivation of political parties and the leaders that led them throughout the period under discussion, his work could benefit from asking the question why some people followed Zanu PF and MDC-T than MDC, which supposedly articulated a clear vision for Zimbabwe and Africa at large.

Second, this anthology is heavy on the public life and less on the private life of Mutambara.

While Mutambara has written tomes about politics and his autobiography is rich in ideas, it reveals very little of his social side other than his wedding and the birth of his children.

Third, the sheer weight and volume (544 pages) of the book does not lend itself to love at first sight.

Notwithstanding these minors, this is an interesting, original and self-indulgent autobiography which is a must-read for all those who are yearning for social and economic transformation in Zimbabwe and beyond.

Gorden Moyo is the Public Policy Research Institute of Zimbabwe director and senior lecturer, Department of Development Studies, Lupane State University.