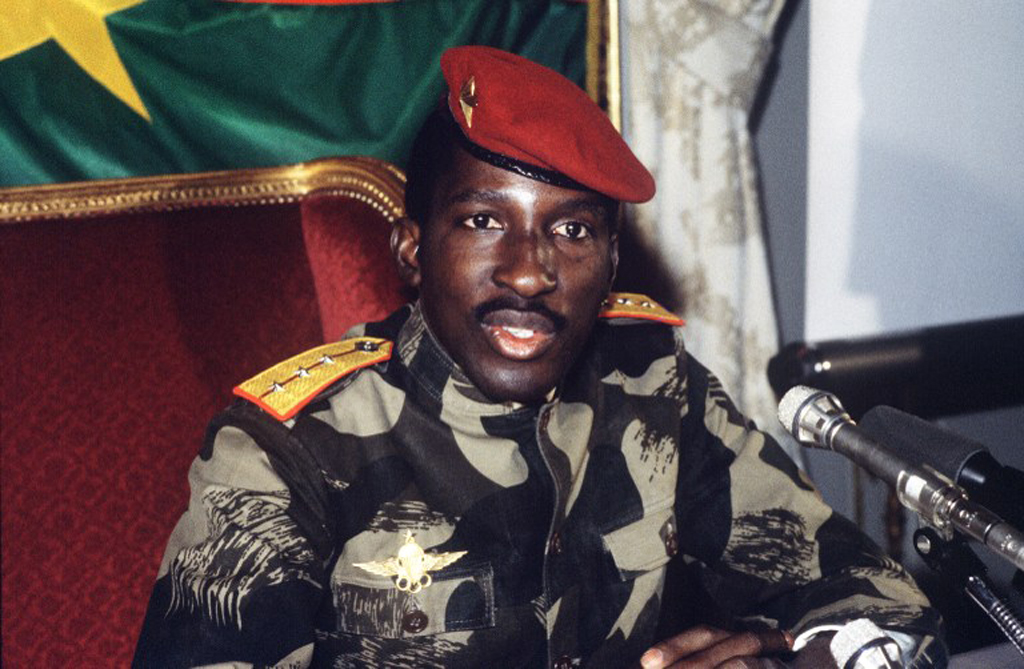

Born on December 21, 1949, Thomas Isidore Noel Sankara, one of Africa’s most iconic, illustrious, heroic, upright revolutionaries and promising sons, ruled Upper Volta, which he renamed Burkina Faso (the Land of Upright People) after he seized power from a repressive regime of more conservative generals, in a popularly supported military coup on August 4, 1983 at the age of 33. He overthrew controversial tyrant Jean Baptiste Quedraogo. The aim of the coup was focused on two main goals: first to eliminate endemic corruption and, secondly, to end the dominance of former colonial power, France.

The Sunday maverick with GLORia NDORO-MKOMBACHOTO

Sankara’s transformational and visionary leadership turned Burkina Faso from a sleepy West African nation, which was known as a catchment for contract labour for neighbouring countries and whose people were perceived to be submissive and dependent, to a country that was beginning to be revered as on a path to self-determination and sufficiency.

As he changed his people’s mindsets, tooling them with the best ammunition ever, ideas and confidence, he made enemies overseas, abroad and within his government for daring to challenge the status quo and refusing to compromise on ideals that he held so dearly about his vision.

One thing led to the other and after being warned several times by his Intelligence minister that his second-in-command, close friend and Defence minister Blaise Campaore, was plotting to topple him, he was callously butchered without resistance at the Presidential Palace on October 15, 1987 with 12 of his aides. They allegedly cut him up into pieces and buried in a shallow grave while swiftly announcing through the media and issuing a death certificate to that effect, that he had died of natural causes.

In May 2015, Burkina Faso authorities exhumed the remains of Sankara as part of a first comprehensive probe into his assassination. He was determined and fearless till the end. Apparently a week before his demise, he had declared that “While revolutionaries as individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill ideas.”

Here are 12 lessons Zimbabweans can learn from the lesser-known presidential life of Thomas Sankara.

- Sankara mantra was simple and specific – have enough, but not far much more than you need. As a charming, compelling Marxist revolutionary and pan-Africanist theorist, Sankara believed in the equality of all Burkinabes. Because he believed every citizen to be equal, it was his sincere conviction that no one was above nor below the presidency. So he kept it real, sometimes arriving to work riding a bicycle.

He was certain that the wealth of the country was adequate for everyone to have enough for themselves and their families, but not to amass wealth to primitive accumulation and consumption levels now widely touted in reality shows and social media as normal.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

- He was a visionary with razor sharp focus, committed to action and service delivery to the masses. Agriculture, health, education and infrastructure development were his major thrust as evidenced by the following:

Sankara vaccinated 2,5 million children against meningitis, yellow fever and measles in a matter of weeks without aid from foreign donors.

Sankara initiated a nation-wide literacy campaign, increasing the literacy rate from 13% in 1983 to 73% in 1987.

Using local resources and without development aid, Sankara built roads and nearly 100km of a railway line to link the nation together.

During his reign, wheat production rose in three years from 1 700kg per hectare to 3 800kg per hectare, transforming the country from a basket case to a bread basket.

On the localised level, Sankara also called on every village to build a medical dispensary and had over 350 communities construct schools with their own labour for their own benefit.

As a transformational leader, Sankara focused the state’s limited resources on the marginalised majority in the countryside. He believed in the self-reliance of African people. When most African countries depended on imports of staple food and debt plus grants for development, Sankara promoted local production and the consumption of locally-made goods.

Sankara believed in changing mindsets and giving confidence to his people to be masters and mistresses of their own destinies, firmly believing that, with perseverance, hard work and collective social mobilisation, it was possible for the Burkinabè, to solve their problems which were mainly centred around food shortages and access to clean drinking water.

- Sankara was proudly Burkinabe supporting the local cotton industry. According to thomassankara.net, he demanded that “public servants wear a traditional tunic, woven from Burkinabe cotton and sewn by Burkinabe craftsmen.” The reason being to rely upon local industry and identity rather than foreign industry and identity.

- Sankara was disciplined, demanding, idealist, rigorous and an organiser with an acute sense of right and wrong. Ernest Harsch, author of a recent biography of Sankara, quotes a former aide describing Sankara as “an idealist, demanding, rigorous, an organiser. This discipline and seriousness started with himself. He had been first among top leadership to voluntarily declare his modest assets and hand over to the treasury cash and gifts received during trips.”

According to a 2015 report written by Mohamed Keita for qz.com, Sankara “He led one of the most ambitious programmess of sweeping reforms ever seen in Africa. It sought to fundamentally reverse the structural social inequities inherited from the French colonial order.”

As head of state, Sankara was not threatened by women and affirmed them while promoting gender equality. Sankara appointed females to high governmental positions, encouraged them to get an education and work. He encouraged women to join the military where they had been previously excluded.

Sankara outlawed female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy in support of women’s rights and gender equality.

He granted pregnancy leave during the educational periods of women. As a keen and active motorcyclist, he formed an all-women motorcycle personal guard.

- As a creative, Sankara wrote the local anthem himself. Sankara had an unusual passion for music which he learnt both at home and in the Catholic Church. He played the guitar with his father at home, whom together with his mother would have wanted him to be a Catholic priest. A Burkinabe musician Sam ‘sk Le Jah remarked that “Perhaps if (African) presidents played music, they would have more humanity in their hearts.

- As president, Sankara disdained formal pomp and banned any cult of his personality. When asked why he did not appreciate his portrait being hung in public places across the country, as was the norm for other African leaders across the continent, Sankara replied “There are seven million Thomas Sankaras in Burkina Faso. If they all cannot be hung up, then mine stays down.”

- Sankara banished bootlicking officiousness among government officials. He did not make rules that he himself did not adhere to. No one was above farm work, or gravelling roads — not even the president, government ministers or army officers.

In Ouagadougou, Sankara converted the army’s provisioning store into a state-owned supermarket open to everyone. Apparently this became the first supermarket in the country.

He sold off the government fleet of imported Mercedes cars and made the Renault 5, the cheapest car sold in Burkina Faso during that period, the official service car of the ministers.

He reduced the salaries of all public servants, including his own, and forbade the use of government chauffeurs and 1st class airline tickets for government business travel.

Sankara forced civil servants to pay one month’s salary to public projects. The reason was to demonstrate that civil servants serve not save themselves at the expense of the public.

Consistent with his mantra for equality for all, he shunned the use the air conditioning in his office on the grounds that such luxury was not available to anyone, but a handful of Burkinabes and therefore not a necessary luxury for him.

Sankara did not hesitate to publicly admit mistakes and take corrective action, a rarity in Zimbabwe.

- Sankara was an environmental champion before it became a fashionable enterprise. During his four-year reign, Sankara planted over 10 million trees to prevent desertification in Burkina Faso. At the time of writing this article many Zimbabweans in previously commercial farming areas are cutting down the precious indigenous Musasa trees to resell as firewood or curing tobacco. This is going unchecked because the Environmental Management Agency lacks the capacity to monitor countrywide.

- Sankara advocated and promoted the concept of a united front of African nations to repudiate their foreign debt. According to thomassankara.net, Sankara “spoke in forums like the Organisation of African Unity against continued neo-colonialist penetration of Africa through Western trade and finance. He argued that the poor and exploited did not have an obligation to repay money to the rich and exploiting.” Yet today, more than three decades after Sankara’s death, African leaders continue to travel lavishly with begging bowls asking for debts and aid Africa does not need.

- To achieve this radical transformation, Sankara increasingly exerted authoritarian control over Burkinabes. As a result, he ended up restricting press freedom and banning unions as he was convinced they would respond at cross purposes with his vision.

Sankara also got to trying corrupt officials publicly in what was referred to Popular revolutionary tribunals. Whilst this was popular with the masses it put him on a collision course with the alienated middle class and those adamant on being on the public purse’s gravy train.

- Sankara died as he lived, with empty pockets..Living for ideals he stood for, as President of Burkina Faso, Sankara lowered his salary to $450 a month, an amount he believed was adequate for him and his family.

When he was assassinated on 15 October 1987, his possessions were limited to a car, four bikes, three guitars, a fridge and a broken freezer. Harsh quotes family members as saying that “Sankara told them not to expect any benefits from him because he was president. In fact, by the time of his death, his kids attended the same public school, his wife was reporting to the same civil servant job, and his parents lived in the same house.”

If Sankara could transform Burkina Faso in a mere four years, with nothing but ideas, courage, commitment, discipline, will and hard work, so can we. Zimbabwe possesses abundant resources enough to feed its citizenry and beyond without begging from predators from either the East or the West.

Need I say more?

Gloria Ndoro-Mkombachoto is an entrepreneur and regional enterprise development consultant. Her experience spans a period of over 25 years. She can be contacted at [email protected]