BY TATIRA ZWINOIRA

ONLY 24% of people between the ages of 18 and 35 in Zimbabwe are formally employed while the rest are either self-employed in the informal sector or are sitting at home without jobs, a new British Council report shows.

Young people make up about 60% of the 14 million population according to the 2017 official survey.

A report titled, Next Generation Zimbabwe January 2020 by the British Council, which is part of the organisation’s global research series in transitioning countries, found that youths are in a challenging socio-economic environment which made it extremely difficult for them to eke out a living.

“From our research, 24% of young people earned a living from formal employment, while 35% earned a living from informal employment. Forty-one percent of young people were dependent on other people for their livelihood. The total percentage employed (either formally or informally) was 59%,” reads part of the research findings.

“In line with the general economic trends of contemporary Zimbabwe, most youths were not formally employed. The majority of the young cohort (18- to 24-year-olds) were dependents, while there was an almost equal distribution of informally employed, formally employed and unemployed/dependent youths in the middle youth category (25 to 30 years).”

The research went on to state: “Less than 32% of the 30 to 35-year-old youths were formally employed, while over 55% of them were employed in the informal sector and around 13% were unemployed with no viable livelihood options and hence dependent on other people.”

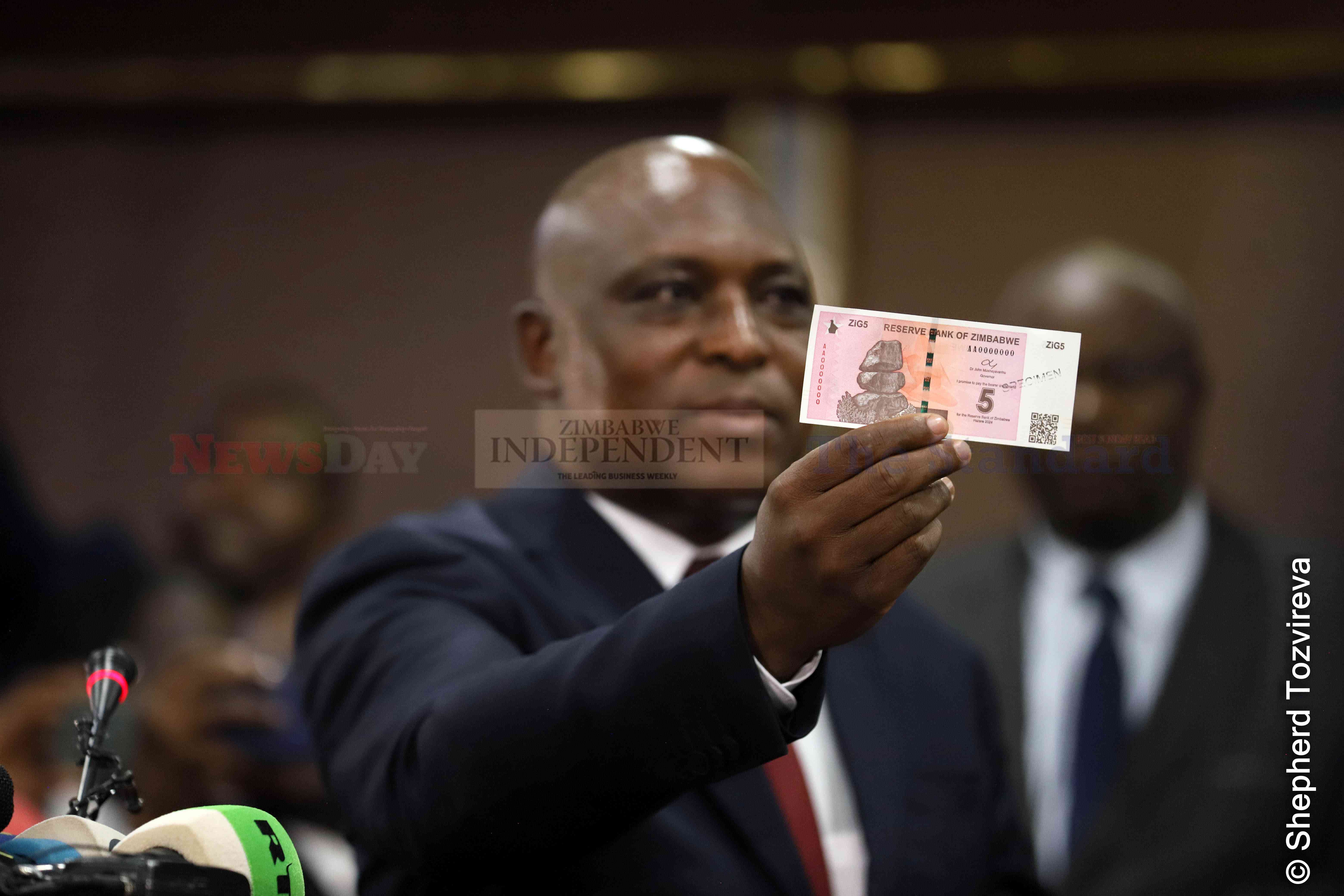

The report comes at a time when companies are rationalising staff amid worsening economic conditions driven by the continued fall of the Zimbabwe dollar (ZWL) that continues to erode the earnings of companies. The fall of the ZWL has resulted in hyperinflation.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

When analysing limited opportunities for earning a living through formal employment, Zimstat’s Inter-Censal Demographic Survey of 2017 argued that the Zimbabwean economy had undergone structural regression following massive deindustrialisation and informalisation.

Despite the notable economic rebound between 2009 and 2018, economic growth has focused more on the exploitation of natural resources (particularly precious minerals) than manufactured products.

“This has huge implications for employment creation and poverty eradication, given the capital intensity required in mining and its enclave nature,” reads part of the report under review.

Once in formal employment, the report under review found that several challenges emerged for young Zimbabweans.

In all age groups and locations, the greatest challenge faced by employed youths was low remuneration which was more pronounced in rural areas among the younger youth cadre, who are likely to be unskilled and as such can’t get higher wages.

“Other workplace challenges include limited career development and unfavourable working conditions. Respondents from across the country have given the following quotes which give a first-hand account of life in the workplace in Zimbabwe,” reads part of the report.

“Most of the complaints centre on low remuneration and limited tools to get the job done; some of the below respondents from Bulawayo and Siachilaba also shed light on limited employee wellness support, which could lead to high levels of demotivation at the workplace.”

The report found that the rights of workers have become secondary as people are desperate and jostle for the few available jobs.

“Agriculture dominates the labour force activities in rural areas, while manufacturing is more prevalent in urban areas. Despite the participation in agriculture and manufacturing, the high unemployment rates limit the union power of labour in the sector,” reads part of the report.

“Although mining is significant in major state policies such as the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio-Economic Transformation (ZimAsset), which dominated the twilight of Mugabe’s rule, it is absent from the common industries that absorb young Zimbabweans.”

On average, formal employment wages range between ZWL$500 and ZWL$2 000 whilst in the informal sector it’s ZWL$500 and ZWL$1 000.

These earnings come as the monthly cost of living in urban areas went up at $4 412 at the end of December 2020, according to official statistics.

“As the Zimbabwean economy continues to shrink at an alarming rate, as it fails to deliver in terms of growth and consequently employment creation, a significant number of youths have, over time, resorted to entrepreneurship as the only means of making a living,” reads the report.

The report under review was based on research findings from all of Zimbabwe’s provinces with the sampling process within the age group of 18 to 35 years old.

Government has prioritised youth employment, after production, for 2020 through offering incentives to companies including increasing the tax threshold and a tax incentive of ZWL$500 per young person hired.