Many schools have an eagle in their crest; many speakers will encourage children to have an eagle mentality; many school teams will call themselves Eagles. Presumably this is because eagles are seen to be at the top of the bird world; they fly high and soar with effortless ease and minimal effort, taking advantage of thermals and currents, way above most other birds.

BY TIM MIDDLETON

They have incredible vision, seeing minute details from vast distances. They are extremely content on their own, excelling in being alone, alert and apparently aloof. They prey on smaller beings with little mercy or concern. When they move, they move fast and decisively. They rule the skies; they are the successful ones. In short, they look in control, in command and in contentment.

In the light of this, coaches will naturally exhort their charges to have that same mentality if they wish to succeed in sport. To succeed in sport, players need to be so self-centred, self-focussed, putting self first and doing everything possible to be first. They need to be content within themselves and able to work on their own, knowing when to strike and when to soar. They need to be deliberate, decisive, determined. They need to prey on the weaker opponents, just like the eagle. They need to soar, to reach higher and higher and use such competition to improve their performance. They need a certain aloofness, an aura that looks down on others as being inferior. So speak our coaches.

What it boils down to is not so much having an eagle but an ego mentality. Success in sport, it is said, needs strong egos. Scott Jurek, the ultimate ultra-marathoner, speaks of people having to have an ego to compete successfully. Sportsmen need to have belief, need to believe they are better than others and they have to be told that, again and again. What coaches do is boost the egos of the players, to help their charges believe they are the best. Paddy Upton, now a greatly in-demand sports (and life) coach who formed a perfect team with Gary Kirsten in helping the Indian cricket team to win the World Cup, recognised this when he admitted in his book ‘The Barefoot Coach’ that “the international cricket world had been a playground for my ego. It had been about looking good, appearing to be in control, always seeming happy, forever smiling, and being the popular guy.” Top level sport is the playground not of eagles but egos. He realised however that it was not enough; it did not work, nor fulfil.

The problem that Upton and Kirsten found was that “ego makes showing emotion, vulnerability and weakness taboo, while what becomes important is pride, a sense of belonging, adopting the values of society and living up to the public’s perceptions and expectations.” Our ego, our greatest ally in reaching the top soon becomes our biggest enemy; we follow after the wrong prey. We present an image, an aura, and hope that others are impressed by it. We listen only to flattery and dismiss criticism with disdain. We are above all that — but we are so high that our heads are actually in the clouds where we fail to see things clearly — and danger strikes. Ego dictates that our identity is based on our performance yet as the latter can change all too easily, for many reasons, the implication is that our identity changes at the same rate. So then, who are we? We have to believe others who feed us with what will make us believe we are soaring.

Others have also written that the two greatest dangers of professional sports are peer pressure and ego. The sad thing is that at school level we actually feed the ego of our children; instead of raising their esteem we boost their ego to the point where they believe the hype. We make such a big thing of players’ performances, comparing them to previous teams and individuals, praising their results. We give awards and prizes – the best this, the most valuable that; we differentiate them with different colour tracksuits and blazers and ties, highlighting their higher elevation and ability, putting them on a pedestal by granting further privileges. In effect, we set them up to fail, except we do not teach them how to fail. As a result, they come crashing down to earth.

It is not the ego that needs to be raised but esteem — the “S” team, made up of being steadfast, stable, serving, supportive, strong. Real heroes do not have egos: real heroes think of others. They are the ones who fly highest. It is not a matter of looking good, but simply of being good. The ego must land.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

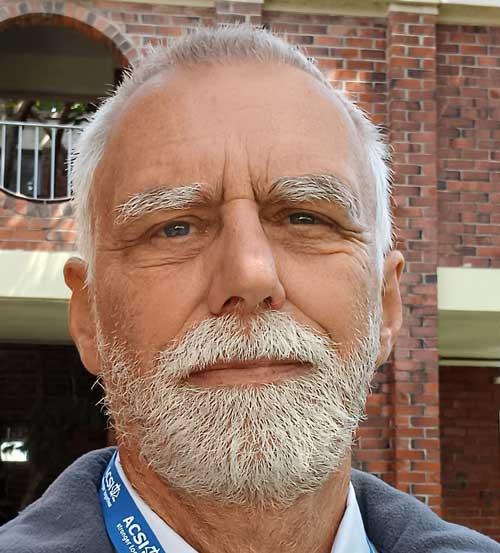

- Tim Middleton is a former international hockey player and headmaster, currently serving as the Executive Director of the Association of Trust Schools Email: [email protected]