“GONE are the days when we used to shortchange people selling foreign currency in order to get more Zimbabwe dollars,” recalls Clive Sibanda a seasoned foreign currency dealer based at Fourth Street, Harare.

With the foreign currency market now having more buyers than sellers because of the recent “dollarisation” it appears the parallel market now has more competition as dealers outdo each other in search of the scarce foreign exchange.

Sibanda’s statement might sound pessimistic but it reflects the attitude among those that trade foreign currency on the black market on the streets of Harare in a dollarised economy that is not backed by production.

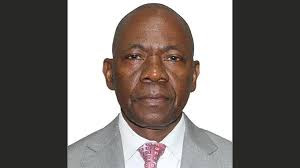

University of Zimbabwe business lecturer, Professor Anthony Hawkins, said Reserve Bank governor Gideon Gono has failed to respond to the crisis in time. “He took too long to address the crisis when figures were showing that major sectors of the economy were not performing,” Hawkins said.

“The crisis has reached unmanageable levels now, his decision needs to be backed by production,” he said.These traders have every reason to believe that their “industry” was slowly dying.

Another Harare economist, John Robertson said the crisis was now frightening and that at the present rate of devaluation the Zimbabwean dollar would trade with the US dollar at any rate the following day.

Robertson said all this, coupled with the huge increases in money supply growth, would never result in a stabilisation of the Zimbabwean dollar.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

“Unless he (Gono) stops printing money, we will not get anywhere,” Robertson said.

All traders and retailers are refusing the local currency despite not having a licence to trade in US dollars.

This has resulted in the value of the local currency almost doubling when buying foreign currency from the dealers.

Yesterday the dollar was trading above $250 billion to the US dollar, while the rand was being exchanged for anything above $25 billion.

As the rate continues to gallop there is now a belief in the market that dollarisation would not turn around the economy and was bound to fail as there was no production to support the policy.

An analysis of the operations of the Reserve Bank since 2003 lends credence to this belief that the market was far from stabilising.

So many foreign exchange policies have been tried but all of them have failed. Some have been withdrawn before they could be implemented. To track these policy changes one has to look at Gideon Gono’s tenure in office since December 2003.

His tenure at the Reserve Bank has been characterised by uncertainty on the foreign currency market.

With each monetary policy, the market has come to expect a raft of new foreign currency policies.

Gono set up semi-weekly Reserve Bank-controlled auctions soon after assuming office.

These auctions, he said, would determine the official exchange rate which had been pegged at $824 to the US dollar in February 2003.

The rate quickly moved to $4 196 to the greenback on January 12 to end the year at $5 730 to the US dollar through the auctions, slightly trailing the parallel market which ended the year at $6 000 for the US dollar.

The year 2005 was to be an entirely different year as the Zimbabwe dollar would tumble heavily against major currencies. The rate moved to $6 200 in March and then $9 000 for the US dollar in May.

The parallel market surged to $14 000 and then to $20 000 against the US dollar in respective periods. In the same year, Gono devalued the dollar to $10 800 to the greenback on July 18.

He then changed it to $17 600 on July 25, before pushing it down to $24 500 on August 25.

The dollar was to be devalued three more times in 2005, starting in September when it moved to $26 003, to $60 000 in November and finally to $84 588 in December.

That did not seem to work as the parallel market continued to race ahead. On July 18 it was $25 000, then $45 000 on August 25, $75 000 in September, $90 000 in November and closing the year at $96 000 in December.

Gono then discontinued the Reserve Bank currency auctions in November 2005 and announced that market factors would determine the exchange rate.

Gono at that time said there were some players who were abusing the auction floor systems.

But even he had to accept that the auctions had been quite successful, despite removing them.

The foreign currency generated in the first quarter of 2004 using the auction system surpassed the total inflows registered in 2003. Over US$192,9 million was raised through the first quarter auctions.

On January 3, 2006, the dollar was again devalued to $85 158: US$1. It moved to $99 201,58 on January 24 and then to $101 195,54 on April 28 where it was to stay until July 31.

The parallel market continued to gallop to reach $550 000 on July 27. After the revaluation exercise on August 1, 2006, in which three zeros were lopped off the dollar, the exchange rate was moved to $250 to the US dollar where it was to stay until August 2007.

However, a special rate of $15 000 was applied for miners, farmers, non governmental organisations, embassies and Zimbabweans living abroad. Meanwhile the parallel market continued to race further ahead of the official market.

It rose from $550 to the US dollar on August 1, 2006 to $1 500 on October 12. It then shot up to $3 200 on January 11, 2007 and on April 1, it stood at $30 000.

But it was not until June 2007 that the real madness began on the parallel market, coinciding with government’s price blitz. On June 3 US$1 was worth $55 000. Twenty days later, it took $400 000 to buy the greenback.

The dollar was devalued again in September 2007 to $30 000 against the US dollar. On April 30 Gono decided to do what the market had been advising him for four years and let the dollar float. Thrilled at the prospect of eliminating the parallel market, Gono’s optimism was unfettered.

“Given the centrality of foreign exchange in the economy,” Gono said, “its pricing has to take into account the need to incentivise all its generators to remain viable, whilst at the same time minimising the intended adverse consequences on the vulnerable segments of society.”

He introduced the Priority Focused Foreign Currency Twinning Arrangement, which allowed the exchange rate to float at market rates.

The interbank rate started on a high, eclipsing the parallel market in the first week as it paid between $165 million and $185 million against parallel market dealer rates of $120 million for the US dollar.

In August Gono removed 10 zeros from the currency in a bid to support his policy to liberalise the foreign exchange market.

BY PAUL NYAKAZEYA