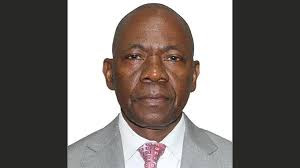

BRETT Chulu recently spoke to Isaac Mazanhi, the human resources manager for a local car assembly firm. They spoke on a number of business issues affecting the motor assembly industry and how Human Resources (HR) is tackling these business challenges strategically. Here are excerpts of the interview:

Chulu: I believe HR professionals are business leaders and so I will be speaking to you as a business leader who happens to specialise in HR. Does this unsettle you?

Mazanhi: Absolutely not. If an HR practitioner is going to add real value to an organisation, they need to have a toolkit that is much broader than specific HR skills.

Chulu: What is the state of car assembly business in Zimbabwe today? Thriving or just surviving?

Mazanhi: As you might be aware, there are only two motor vehicle assembly plants in Zimbabwe — Willowvale Mazda Motor Industries and Quest Motor Corporation. There is stiff competition from South African automakers and from cheap, second-hand Asian imports.

South Africa has its Motor Industry Development Programme (MIDP) initiated in 1995 and running to 2012. In essence, the MIDP creates protectionist framework favouring South African car manufacturers to the extent that it is virtually impossible for the local assemblers to compete with them in both the domestic and export market.

It is akin to the protection offered to farmers in the EU countries. To describe the local assembly industry as thriving is to be economic with the truth!

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Chulu: What are the capacity utilisation levels like for local assembly plants?

Mazanhi: The vehicle assembly plants have been operating at no more than 20% capacity utilisation for over a decade now.

Chulu: At these low capacity utilisation levels you still have to absorb fixed costs. How then are you ensuring that you break-even?

Mazanhi: The quickest and most potent option has been to engage in across the board cost-cutting measures through headcount reduction, freezing recruitment, short-time working and so on. Production is only done in direct response to confirmed orders to avoid tying up cash in stock. Importation of completely built units (CBUs) is also being done on a lower scale to plug part of the gap created by unused capacity.

Chulu: What is the extent of competition you are facing from imported reconditioned vehicles and decommissioned cars mainly from Asia and Britain respectively?

Mazanhi: A large volume of these imports come from Japan. In 2004, a total of 3 401 such vehicles were imported into Zimbabwe. This figure had risen to 10 525 in 2008. This has had the effect of shrinking the new vehicles market from a high of about 18 000 units per year in 1997 to about 5 000 now — a market decline of about 72%.

Chulu: The US dollar has been losing value against major currencies. In particular it has shed 30% of its value against the rand. How has this affected local car assembly business?

Mazanhi: The larger part of motor vehicle components (CKD) is imported from Japan.

The exchange rate movements between the US dollar and the Japanese Yen have an impact on pricing of the final product. For instance, in April 2009, the exchange rate was 95 yen to the US dollar.

As at September 2010, the value of the US dollar had plummeted to 85 yen to the US dollar.

Let’s say hypothetically the landed price of a CKD kit from Japan was US$25 000 in April 2009. The same kit would cost US$28 000 in September 2010 — an increase of 11%. Add local content and manufacturing cost, the final cost of the vehicle will be even higher.

Pricing of locally assembled vehicles is therefore vulnerable to the vagaries of the money market. In order to manage the final price, car assemblers are forced to squeeze their margins.

Chulu: Vehicle financing schemes are popular in the Sadc region to assist customers to purchase vehicles. How viable is this model in Zimbabwe given the prevailing punitive rates of borrowing money?

Mazanhi: Banks such as FBC, BancABC, ZB, Stanbic and CBZ have recently re-introduced vehicle finance schemes. The tenure of the loans range from six to 24 months. Deposits range from 20% to 30% depending on institution.

Interest rates average around 20%. The schemes are not yet viable given the liquidity crunch in our economy.

In contrast, in South Africa for instance, tenure such is up to five years at interest rates of about 5%. Almost every financial institution offers such schemes. Unlike in this country where such schemes favour corporate organisations, individual purchasers can also access such schemes with ease.

Chulu: HR has often been accused of focusing on activity rather than business outcomes. Why is that so?

Mazanhi: Fundamentally, I believe that HR gets a bad press for not understanding the business properly.

HR professionals are still struggling to shake off the “pen pusher” or “tea and sympathy” tag. HR suffers from too much red tape and failing to align its activities with the strategic direction and goals of their organisations. HR is not good at measuring the results of its activities.

Most HR practitioners have social science degrees such as psychology. They are not comfortable using quantitative data. Ironically, in business, the adage “what gets measured gets done” holds true.

Entrepreneurs feel uncomfortable taking business decisions without data. HR must understand how their company makes money and where HR fits in.

Chulu: The emerging view of HR which is still to take root in Zimbabwe is called organisation capability. Organisation capability simply means what the organisation is good at and what it is known for. It is what HR should deliver to make the organisation distinctive. The most common capabilities (HR deliverables) are accountability, collaboration, customer connection, efficiency, innovation, leadership, learning, risk management, simplicity, speed, shared mindset, strategic unity, social responsibility and talent. Which two or three capabilities do you think HR in Zimbabwe should be leading banks to deliver given that a weak banking sector negatively impacts on the health of the motor industry?

Mazanhi: I will opt for one, innovation! As at September 2010, total bank deposits stood slightly over US$2 billion and the top four banking institutions controlled 75% of these deposits.

To all intents and purposes, this is a trickle. HR must assist banks to bring on board innovative products that will assist to mobilise cash and channel it towards productive use. At the moment, there is depositor fatigue and skepticism and this is made worse by the unexplained behaviour of banks sticking to old methods of doing business and expecting different results.

Chulu: These capabilities are intangibles that give investors/financiers confidence in future earnings. For customers the same capabilities when delivered are the brand they experience. In other words when HR helps an organisation deliver these intangibles: share prices, net asset values per share and corporate ratings rise.

How ready is the Zimbabwean HR profession to play such strategic business roles?

Mazanhi: It’s a mixed bag. Some HR professionals have or are enrolling for business and strategic management courses. I know of a handful of HR people who have moved into general management positions in their organisations. However, there are some who are content with playing the narrow administrative role.

They find it an insurmountable task interpreting the business in financial terms, let alone measure their own contribution.

Chulu: How difficult has it been to retain key talent in your industry? Any specific strategic job families seriously affected?

Mazanhi: Turnover has been very low in the industry. We have managed to retain our key talent — artisans, engineers, etc through a cocktail of interventions such as competitive remuneration, offering opportunities for career development, job enlargement and enrichment, a congenial social atmosphere and work-life balance.

Chulu: How widespread are practices to minimise knowledge loss when key talent leaves such as restraint of trade payments, documenting internally generated best practices and knowledge transfer/retention?

Mazanhi: To promote knowledge transfer which is very critical in our skills-specific industry, we have put in place graduate learnership and apprenticeship programmes. Multi-skilling is an imperative such that one employee is able to work effectively on more than one work station. Procedures are documented for continuity. One of the car assemblers is ISO 9001:2008 certified.

Chulu: How much does it cost in monetary terms currently to lose key technical talent?

Mazanhi: The cost of employee turnover is easily overlooked and can reach as much as 150 to 200% of the salary paid to an employee. To put this into perspective, let’s assume the average salary of an employee in a given company is US$20 000 per year. Taking the cost of turnover at 150% of salary, the cost of turnover is then US$30 000 per employee who leaves the company. For a company that employs 200 employees with a 10% annual rate of turnover, the annual cost of turnover is US$600 000! That’s a lot of money in anyone’s book.

Chulu: And for senior executives?

Mazanhi: Going by the above formula, if we are to peg the CEO to rank-and-file-worker pay ratio to be at 20:1, the annual cost of losing a senior executive would be about US$12 million in monetary terms! However, the figure is likely to be much more given the sophistication associated with executive remuneration.

Chulu: You hold very strong views concerning Zimbabwe’s arbitration system. What are the gaps and opportunities available in the current arbitration system?

Mazanhi: Arbitration as part of our labour law is still in its infancy. There are many teething problems. Appointment criteria for arbitrators are obscure, arbitral fees are not regulated, there is no prescribed time frame for coming up with an arbitral award, there is no ethical code of conduct governing the work of arbitrators, the involvement of lawyers in the process makes it look more like the traditional litigation process it is meant to supplant. However, if all these deficiencies are remedied, arbitration presents immense opportunities for resolving disputes faster, cheaply and in less acrimonious ways than the courts. We can borrow a leaf from CCMA in South Africa or Acas in the UK.

Share your views on issues raised in this interview at [email protected].