The concept of decentralisation as a developmental policy invited serious debate during the constitution-making process.

Opinion by Itai Zimunya

The argument mainly advanced by Bulawayo-based civil society institutions was that the Harare-centric developmental formula had failed Zimbabwe.

Unfortunately, that noble argument risked being dismissed as a regional argument marketing the interest of the people of Matabeleland.

Manicaland has played a big role in national development but some of its achievements are getting extinct due to the continuous trek to the capital city.

The theory that the summation of parts is greater than one whole cannot be more valid than now. For a post-colonial resource-rich country like Zimbabwe, development of the country’s parts and districts needs to be brought back to the centre of the policy process.

A collection of strong and developed regions not only eases the socio-economic pressure on the capital city, but makes Zimbabwe stronger.

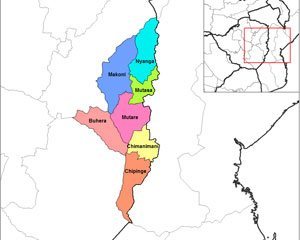

The city of Mutare has an estimated population of 300 000 and is now known as the city of diamonds as both Marange and Chimanimani produce more than 70% of Zimbabwe’s diamond quantum.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Fruits like bananas, peaches, mangoes, litch and avocado among others are produced in its environs.

Rolling mountains with spectacular views, fertile lands and the port that links with Beira is located there as well. The total value of production that takes place in its environs easily tops US$1 billion yearly.

Amidst all this splendour, the city of Mutare proposed a shallow budget of US$18,6 million for the year 2013. There is a paradox here and several questions need to be asked.

To demonstrate how shallow the City of Mutare’s 2013 budget is, it is better to use a comparative analysis with other economic transactions.

In 2012, Mines minister Obert Mpofu, bought ZABG for US$24 million, meaning he is more liquid than a whole city.

How can a provincial capital whose geography contributes US$1 billion to the national developmental matrix only get US$18,6 million to service it? From a pedestal perspective, one may ask where the US$980 million that Manicaland generates is going.

Is it an effect of sanctions, looting or a result of poor developmental policy frameworks?

This focus on Manicaland and Mutare in particular aptly displays how the Harare-centric developmental models have weakened Zimbabwe. It also shows that the demand of a devolved state is not a Matabeleland question, but a national issue.

Firstly, to understand this debate, it is important to state some historical and socio-economic facts on the role of Manicaland to national development. We have the liberty to substitute Mutare with the province of Manicaland since Mutare is the capital city of that province.

That province’s people suffered immensely during and post the liberation struggle due to its long frontier with Mozambique from Gaza in the south to Tete in the north. As late as 1987, security was an issue as apartheid South Africa sponsored cross-border raids targeting villages along the border with livestock, women and girls emerging the biggest victims.

In spite of its illustrious history and its huge contribution to the national economy, Manicaland lags behind other provinces in development. The province, for instance, has no state university.

The city only enjoys US$20 million of the estimated US$1 billion its environs generate every year.

Mutare and much of Manicaland are often serviced by Mozambican radio stations. None of the diamond mining companies in Marange and Chimanimani have head offices in Mutare. The big Russian and South African-owned gold mining companies in Manicaland have offices in Harare.

Tea and timber companies relocated their offices to Harare.

The province has indeed fallen from grace.

The diamond cutting training industry, though private, is being proposed for another province. The aerodrome ever constructed in Zimbabwe after 1980 was built in Marange, to fly out diamonds to Harare for sale as soon as they are mined.

Villagers are left to contend with the silting and poisoned waters of the Mutare, Odzi and Save Rivers.

The fuel refinery at Feruka was closed as the fuel hub was transferred to Harare through the fuel pipeline.

Feruka, once a thriving firm, now lies dead and obsolete. The country lost a chance to import crude oil from Angola, Mozambique or elsewhere and refine its own fuel, all for wanting to bring everything to Harare. What makes this discussion interesting is the fierce refusal for decentralisation by some policy makers, often wrongly arguing that it would weaken or split Zimbabwe.

The story of Mutare is similar to Matabeleland and other provinces whose industries and civilisations are either moving to Harare or closing. So the issue is neither a Matabeleland nor a Manicaland one, but national issue.