In the previous two installments, I was writing about methodologies for dispute resolution and I emphasised that disputes must be settled at the lowest possible level considering that an employment relationship is ideally a private and domestic affair.

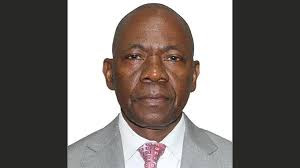

BY REQUEST MACHIMBIRA

Nevertheless, failure to resolve disputes using the available domestic remedies results in the legal formalisation of the dispute resolution mechanism.

Whilst the purposive nature of legislation is to bring finality to disputes, the procedure has its pros and cons.

Employers have often cried foul as a result of either their omissions or commissions in workforce management. The effects have often been unforgiving and in certain instances “unbusiness-like” arbitral awards and judgements.

I am therefore going to highlight the legislative provisions pertaining to both conciliation and arbitration. In terms of section 93 of the Labour Act, a dispute may be referred for conciliation before a labour officer or before a National Employment Centre (NEC) designated agent.

The conciliator is therefore like a mediator. Their role is not to pronounce judgement but to make parties appreciate the legal provisions of a dispute, if it is a dispute of right, and to explain consequences of not settling at that stage. My advice to employers is to avoid over-legalising conciliatory proceedings. This has the effect of hardening attitudes which may result in cases being escalated.

Whether or not you win a labour case, there is a cost, that is, lost man-hours, legal fees, etc. This is undesirable for a nation whose real average capacity utilisation is below 50%.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Corporate energy and resources must be deployed more on productive activities, innovations and inventions.

In the event that parties fail to come up with a mutually agreed settlement, section 93(5)(c) provides that the labour officer, “may refer the dispute to compulsory arbitration if the dispute or unfair labour practice is a dispute of right;” Such a dispute will therefore be heard by an Arbitrator who, in terms of section 98(9) shall, “…..have the same powers as the Labour Court” in hearing and determining a dispute. However, the use of ‘may’ implies that referral is not mandatory.

In terms of Section 93(7)(a), a Labour Officer is not necessarily obligated to refer a dispute to compulsory arbitration however the Labour Act does not necessarily spell out circumstances which may entitle a labour officer/designated agent to exercise that option.

As a result, labour officers and designated agents have systematically and conveniently converted themselves into arbitration post-offices.

Once a dispute is lodged no matter how frivolous, it finds itself landing on the arbitrator’s desk via the labour officer. Parties to disputes must invoke this provision. Where a party is approaching proceedings with dirty hands or with a frivolous claim, I am of the opinion that provisions of Section 93(7)(a) must be invoked.

Request Machimbira is the Group Chief Executive Officer for Proficiency Consulting Group International and StrategyWorld Consulting. For feedback, [email protected] or visit website www.proficiencyinternational.com. Phone 0772 693 404/ 0776 228 575. Facebook Profile: RequestTinashe Machimbira