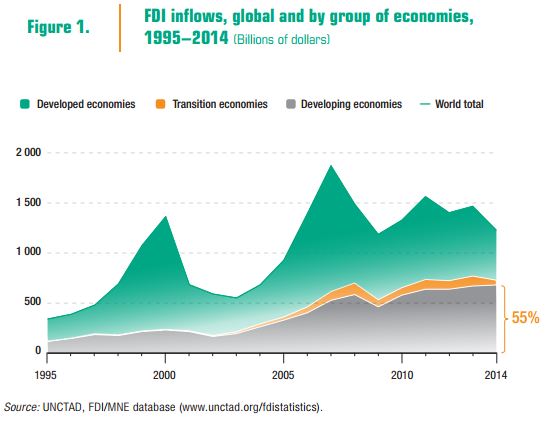

A United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) 2015 World Investment Report shows that global foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows declined by 16% to $1,23 trillion in 2014, mostly because of the fragility of the global economy, policy uncertainty for investors and elevated geopolitical risks. Despite the decline, inward FDI flows to developing economies rose by 2% to reach a record high level at $681 billion. Developing countries continued to attract two thirds of the Greenfield (new venture) investments. FDI inflows to Africa remained flat at $54 billion.

IN THE MONEY BY NESBERT RUWO & JOTHAM MAKARUDZE

FDI is defined as the direct investment capital flows in the reporting economy. There should be control or significant degree of influence by the investor on the investee enterprise that is resident in the FDI reporting country. Ownership of 10% or more of the ordinary voting shares is generally used as the criterion for determining the existence of a direct investment relationship.

In 2014, Zimbabwe’s FDI inflows rose by 36,3% to $545 million, which accounts for 1% of Africa’s FDI inflows.

Greenfield investments were $457 million. Africa as a whole received $54 billion in FDI, led by South Africa ($5,7 billion), Mozambique ($4,9 billion), DRC ($5,5 billion) and Nigeria ($4,7 billion). Zambia’s FDI inflows were $2,5 billion.

The key drivers to attracting FDI include investment policy measures geared predominantly towards investment liberalisation, promotion, facilitation, and reduced entry conditions and restrictions. Promotion of investment in sustainable development sectors such as infrastructure, health, education, and environment protection, through public-private sector partnerships will underpin future investment in FDI recipient countries. Given the significant requirements for capital, governments cannot do it alone. In some instances, reformation of the international investment agreements regimes could be used to spur international investors.

Given the shortage of public funds in most developing countries, the obvious solution is to invite greater private sector participation. In public-private partnerships (PPPs), the public and private sectors join forces to design, finance, build, manage or maintain infrastructure projects. Such partnerships can take many forms depending upon the exact risks and responsibilities allocation matrix. They can take the form of service contracts, delegated management contracts, and construction support such as Build-Develop-Operate (BDO), Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) and Build-Operate-Own (BOO).

The main modes of entry for private participation in infrastructure have been joint ventures, Greenfields through BOT, BOO, Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT), Design-Build-Finance-Operate (DBFO) and Build-Lease-Transfer (BLT). PPPs have been instrumental in attracting FDIs, especially in the utilities sector within the telecommunications, energy, transport and water and sewerage sub-sectors.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

In a vote of confidence on the country’s investment opportunities, Africa’s richest man and investor, Aliko Dangote is set to invest $1,2 billion in three Greenfield Zimbabwean projects. The Zimbabwe Investment Authority announced that it has issued licences to Dangote for a cement manufacturing, coal mining venture and a power plant. Inflows like these are set to encourage other investors to carefully consider Zimbabwe as an investment destination. Dangote’s investment will be a massive investment by any measure — it represents about 13,7% of the Zimbabwe’s GDP and is a significant investment for Dangote Group; Dangote Cement, which contributed 70% of group revenues, made a profit of $0,9 billion in 2014.

Empirical evidence shows that in order to compete with other countries in attracting more FDI, a country should make its investment climate significantly better and conducive to foreign players. This requires considering firm-specific motivations, productive efficiencies as well as addressing infrastructure bottlenecks. While this could be seen as a chicken-and-egg scenario for the country, our view is that the PPP model could be used to address infrastructure bottlenecks which will go a long way towards attracting FDI. There are a lot more positives that can be harnessed in marketing the country — an educated populace, strong work ethic, and natural resources (minerals, arable land and generally good climate).

In our experience, we see that FDI and portfolio investment capital tend to follow strong institutional and governance structures. There is evidence that the unpredictability of laws, regulations and policies, excessive regulatory burden, government instability and lack of commitment play a major role in deterring FDI. Investments like the proposed Dangote $1,2 billion into Zimbabwe may not be forthcoming if the country does not have an honest and critical look at the deterrents of FDI.

The World Bank’s Doing Business Report 2016 said Zimbabwe’s business reforms on getting credit and protecting minority investors helped in making doing business in the country easier. The country was ranked 155 out of 189 countries, slightly down from the revised 153 in 2013. The ranking was dragged down by low rankings in the areas of starting a business, constructions permits, availability of electricity, and enforceability of contracts. There is scope to change the view of international investors on the country.

Nesbert Ruwo (CFA) and Jotham Makarudze (CFA) are investment professionals based in South Africa. They can be contacted on [email protected]