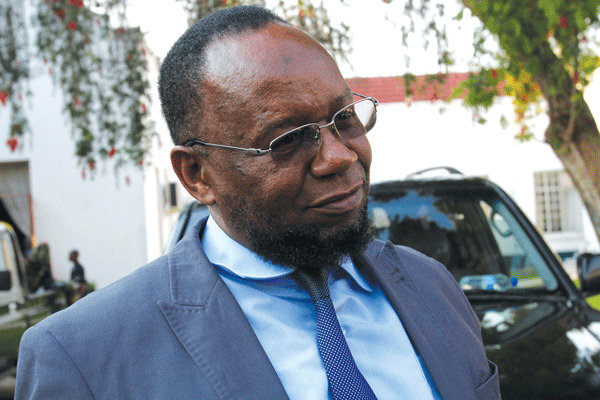

Primary and Secondary Education minister Lazarus Dokora has courted controversy with a litany of changes in the country’s education system since he was appointed to head the crucial ministry in 2013.

the big interview BY OBEY MANAYITI

From the controversial national pledge to the new school curriculum, few reforms introduced by Dokora’s ministry have been a hit with parents and teacher’s unions.

He has been grilled by parliamentarians on the new curriculum and the Progressive Teachers Union of Zimbabwe is pushing a petition in an effort to stop the implementation of the reforms.

However, Dokora (LD) insists that those challenging the new curriculum are misinformed or just being mischievous.

He told our reporter Obey Manayiti (OM) in an interview last week that President Robert Mugabe was behind the changes in the new curriculum and his ministry would not be distracted by the murmurs of disapproval. Below are excerpts of the interview.

OM: Some school development associations such as Dadaya have taken you to court challenging the new school curriculum. Teachers unions have also expressed reservations about the reforms. In your view, what do you think are some of the reasons behind the resistance?

LD: I’m not sure whether I would start there because you are speaking of some select responses that have come through.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

I think what you need to understand is the journey and we didn’t start that journey. It was started many years ago. At independence, if I am to take you through that perspective, we collapsed two distinctive systems into one.

The president, by end of the 1980s, said we collapsed all systems into one but let’s now look inside the system to be able to say, with this kind of education can we assure growth of our national economy.

Remember (the late Bernard) Chidzero was minister of Finance and he spoke about growth with equity and the search was set to see if we had those skills to ensure growth with equity.

By 1997 the president then appointed a Presidential Commission of Inquiry which meant the highest office in the land was simply saying to the nation we must pay attention to this and then they worked over a period of two years, travelling all over the globe and produced a report which is sometimes called the Nziramasanga Commission report.

We then get this report presented to cabinet in 1999 and cabinet says yes it’s okay and the minister of Education can proceed to implement it.

I can then show you in terms of the implementation matrix that time and the ministry looked at that task and were expected to do a lot of things such as civic education, mainstreaming skills in the curriculum and also dealing with the issue of ICTs, saying we need to buy second-hand computers and push them into schools and you will recall that the president himself began a computerisation programme donating thousands of computers to schools.

The second recommendation made there was to mainstream early childhood development (ECD) because the world had transformed and early childhood development had become a key and foundational step for any child.

We were busy in this country trying to make kids pass Grade 7 but we were not taking care of the foundational stages, so there was a disconnect and how did the ministry answer to that?

The ministry tried to do a reform and generated circulars in 2004 which said attach ECD classes to the primary school. Our people are good at reading and they literally did that.

They attached an ECD block to their primary schools. It meant that if we had a boundary of a primary school and when you are attaching an ECD block you put it on the edge of the school.

These guys were outside the purview of the school and so you see the contradiction of trying reforms by administrative measure while looking at a report which says mainstream. The disconnect continued to subsist.

One of the things we did in the reform was to say let’s mainstream ECD and that is what we took to cabinet in 2014, saying ECD A at four years, ECD B at five years and then Grade 1 at six years.

We restructured these up to Grade 2 into an infant school. That is the first key mainstreaming of the Nziramasanga Commission.

Was there opposition to that, of course there was. You reported on it some of you and I remember waking up one day reading Dokora brings Zimsec to Grade 2, which was a total misreading because we were laying the foundation for the primary sector through this infant school.

OM: So why is there resistance among stakeholders within the education sector?

LD: I am trying to give you a response to that. You cannot get a blow to blow before understanding the material contextual factors.

I gave you the example and there was resistance. So who was mounting the opposition of the inclusion of kids into the schools?

It was several groups and some were the owners of ECD centres because when you say these kids are now in school, it means where they were earning $500 a child every month that kid will certainly stop going there.

Is it good for our people? Of course, it is good for our people because the ECD centres are private entities and the government said these kids must be in schools and they go into government schools and council schools and so on and what do they pay there, $10 or $20 etc.

This is far much cheaper and the instruction from the mandate was to get our people access to education and we are fulfilling that.

Some of the teachers were saying these little kids are difficult to organise, but we need them in school rather than having them out there in the hands of untrained people.

So was the resistance informed? You take your choice from self-interest, business and fears on the capacity to teach them and there were others who said do we have teachers for them.

You can’t produce teachers for that level unless you have a policy that says they are now in school. Then the systems that produce teachers begin to produce to fulfil that.

But you cannot say all the teachers must be in place. Who do I say produce teachers when infant education is not part of the mainstream?

One of the recommendations was to get schools to have second-hand computers. Second-hand computers might no longer be viable solutions.

The ICT tools themselves have come down in terms of price so the tools are available. Tablets, laptops and the president distributed desktops so eventually as part of the reforms, we said let’s get the inclusion of ICT tools.

Again you ask me is there resistance, yes, and who is resisting. I don’t know whether to call it resistance really because when the president put these computers in the school systems two years, three years down the line I visited some schools and found these computers safely wrapped away.

Lack of knowledge, lack of skill can also produce a reaction which says this is going to threaten my status as a teacher.

OM: But looking at that, internet penetration in Zimbabwe is still slow and many schools in rural areas might not have an internet connection or electricity to power those machines. What are you going to do to solve that problem?

LD: Well, you ask me a question which begs me to remind you again about which starts. Do you prepare the teachers you want for infants ahead of the policy or do you need the policy to inform the teacher production?

Do you enable schools to begin the journey of ICT incorporation or do you start by saying let me have all schools 100% electrified or teachers trained? It doesn’t happen like that.

OM: But will it not be a disadvantage to some schools, especially those in rural areas?

LD: That is why I am responding to you by being practical. Which starts [between] the policy that enables or the perfection of deployment?

Do I sit here and say let’s have all the schools electrified then you say to the president you can now start giving out computers. We must begin from where we are.

A lot of schools that have power were the initial stock of schools that have received the computers. The other lot of computers in schools are through the initiation of schools themselves.

You can put content on tablets or laptops. You don’t need to be connected to the internet always.

OM: Are you satisfied with the manner you communicated the changes to the curriculum? LD: I don’t know if I should sit here to preside over my own trajectory but what we can say is that there was massive participation of our stakeholders in the consultations as part of our efforts to maintain that organic link with our stakeholders.

OM: What is your reaction to complaints by teachers that they have been reduced to clerks because there is no time for lesson delivery, no learning/ teaching materials for the new curriculum?

LD: I am not sure if they must be telling you things like that because you are not a teacher yourself. They are probably telling you a tall story hoping that you will write that.

You see for example, the little ones at infant school, their lessons are very short, about 15 minutes, and after that there is some activity and they move around in an organised fashion and that is all.

Perhaps that week they have a tour at the school to understand their environment and it will collapse two or three lessons. Is that congestion?

The bigger kids could actually have a tour to observe things within their vicinity. It’s not like they must have a lesson which keeps them all the time in the classroom.

We have said we are too theoretical, academic. We sit and talk and doing things like the longest river in Africa, the tallest mountain in Africa, the most popular city in Africa, yes it’s some form of knowledge but really, really….

What some of your interlocutors are saying now we have to think outside the box and I have a lot of respect for teachers with pedagogy, those are the teachers because they will understand that when they are given a syllabus and a teacher’s handbook, the material to transact with the kids, they will deliver.

OM: Do you think schools with hot sitting and children that have to travel over 20km to school every day will cope, considering that lessons now have to stretch to late in the afternoon?

LD: I thought you would actually say the updated curriculum makes learning pleasurable. We embarked last year from May on an action granted to ask Cabinet that we want to feed all our kids.

We are starting with the infants. It’s not accidental. We understand what it means for a kid who is hungry to sit in a class or to take part in an activity and so we argued our case in Cabinet and Cabinet was gracious enough to accede to the request.

So nutritional needs of the learner are key so when you talk of walking 10km to school and another 10km back, that shows the inadequacy of our infrastructure.

We must not exaggerate these things. We have not said we are bringing in solutions to the infrastructure. Remember in 2013 I had a consultation workshop that was dedicated to the infrastructure needs of the ministry.

We have not invested in the sector and let’s not use that deficit to then compromise the desire to compromise skills to the young learners otherwise we perpetuate the same problems.

OM: There is also a feeling that the new curriculum shuts the door on repeaters. What is your comment on that?

LD: The beauty of your question is that it is only a feeling and it is not based on fact because our experts in assessment have spoken to us and laid out the rules of that continuous assessment but it remains valid over a two-year period.

OM: Schools have passed on the cost of printing materials related to the new curriculum. Are you not overburdening already impoverished parents?

LD: No, not at all, absolutely not. We have not said schools should print. It is provided for in our 1 300 clusters, we have some of the latest printers/rixographs that we have stocked here, photocopiers and latest computers.

The district school inspectors are responsible for assisting schools to get their materials done and just recently I have been in touch with my colleagues from ICT [ministry] who are helping me further by providing the 1 300 placed online so we bring online connectivity closer.

However, it is not going to be for all the schools but we must begin the journey together.

OM: On the new curriculum, how do you hope to complement the ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education whose thrust is to promote science technology, engineering and matematics (Stem)?

LD: I don’t know whether that is a fair question [or not]. You are asking me how do I complement another ministry. We never had science in infants.

When you talk about popularisation of science and working with numbers, we need to demystify this whole zone of mathematics and science.

A lot of people who went into tertiary colleges didn’t have mathematics but guided by this updated curriculum, we are saying the future cannot avoid mathematics.

By saying at the infant level let’s begin to play with numbers, I tell you one thing that our system says Grade 1 should not count beyond 10, for 35 years we kept it at that but the rest of the world didn’t stop there.

I can give you a brute example of four-year-old kids who are able to take your cellphone and punch some numbers and dial somebody. That cellphone number has more than two digits.

It’s our system that remained stalled while the rest of the global issues were progressing. We start our journey for Stem in infants and the responsibility to get these kids excited and play with numbers and excited with numbers makes our kids curious and get on some projects.

I have said operate in the language that the kids understand. If I don’t teach them science and maths then I deny them the greater portion of their future.

By the time the kids are in Grade 3, they are ready to do science and technology and begin to codify some of those concepts.

OM: Does this mean our children’s future in terms of opportunities is broadened?

LD: We have just opened up the space for the kids’ potential. Every kid’s dream really should be carefully worked into a study plan.

When like the MPs were telling me that there is 0% pass rate it is painful for me because I can see why they are asking but I can see why they cannot understand my response.

All they want is that these kids pass but you are forcing everybody into a narrow grouping of academic work. Not everybody is academic and even those that we push into academics and have 17 As.

I have asked a question, what can you do? In short, we have educated this kid to be frustrated. They are out in the streets selling airtime because they cannot do anything. They are educated to be employed.

OM: Apart from the new curriculum, teachers complain that your ministry is trying to force a dress code on them, which among other things stipulates that red ties are now for special occasions and that flat shoes are not allowed. What is the rationale behind that?

LD: What dress code? You should ask me whether I am doing something in that direction. I only read about it in your paper and I don’t know about it.

I am not an employer and how will I set a dress code? Who am I to set a dress code to the people I don’t employ? Anyway, I have spoken, did you hear me talking about dressing?

OM: Are you proud of the reforms you have introduced in your short stint as Education minister?

LD: I try to skirt these issues when they are taken back to the person. I don’t credit myself with any pioneering work, no.

I listen carefully to what the president has been saying. Even before he set up the Nziramasanga Commission he had started talking about education.

We can’t do more than what we can manage but certainly, the vision is much greater.

There is no way we can undertake the reforms of this magnitude without the step and march with the parental stakeholders so we have merely been able to do what we are trying to do.