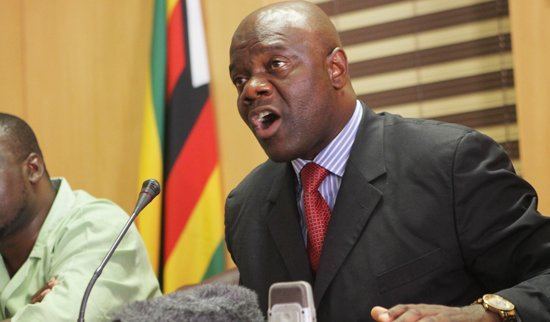

Arthur Mutambara is probably best known as Zimbabwe’s former deputy prime minister from 2009 to 2013. In those four years, Mutambara, Morgan Tsvangirai and Robert Mugabe were the principal leaders in a power-sharing government brokered by ex-South African president Thabo Mbeki, on behalf of the Southern African Development Community (Sadc), following a disputed election.

the Mark Chavunduka column BY Miles Tendi

Mutambara left active politics for a career in the private sector when the power-sharing government’s tenure ended in 2013.

He has used his retreat from the hurly-burly of active politics to quietly write up a trilogy of works, broadly entitled: In Search of the Elusive Zimbabwean Dream: An Autobiography of Thought Leadership.

The first in this trilogy of works, which is the main focus of this review, is The Formative Years and the Big Wide World (1983-2002). The Path to Power (2003-2008) and The Deputy Prime Minister and Beyond (2009- ) are due to be released in the coming months, completing the trilogy.

The goal of The Formative Years is to set out the ideas and historical processes that shaped the young Mutambara’s political thinking and conduct from high school to his university years in Zimbabwe, England and the United States of America.

Mutambara’s later political convictions and actions, discussed in The Path to Power and The Deputy Prime Minister are therefore best understood against the backdrop of his early ideas expressed in The Formative Years — a compendium of Mutambara’s unadulterated written public statements, speeches and essays from 1983 to 2002.

Thus, the book offers us an appreciation of Mutambara’s early ideas and creative expression in their unmodified form and in the context of the prevailing philosophies of those years. This is a bold move.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Mutambara deserves credit for being brave and honest enough to publish unmodified, his early ideas because some of them are not complimentary of his political outlook at the time.

Take for instance Mutambara’s initial uncritical support for Mugabe’s undemocratic one-party state ambition.

The absence of a central place for gender politics in Mutambara’s The Formative Years will also rankle its feminist readers.

The Formative Years engages a range of themes. It opens with the young Mutambara’s starry-eyed perceptions of the ways of guerrilla fighters in Zimbabwe’s 1970s liberation war.

Later, we read his critical turn against the one-party state ideal and escalating government corruption, amid late 1980s radical student politics, which Mutambara led at the University of Zimbabwe.

While his initial stance on the one-party state changed, Mutambara’s adherence to socialism remained unbroken in his undergraduate years, underlining his durable commitment to an ideal of social and economic justice.

Mutambara’s views on national politics are complemented with his standpoints on the more immediate concerns of a late 1980s university student in Zimbabwe.

The sanctity of academic freedom, opposition to corruption within the Zimbabwe Students’ Union and the betterment of university students’ declining living conditions on campus, among other direct concerns, were important sites of struggle for the youthful Mutambara.

His statements on these matters showcase the radical beliefs, flamboyant rhetoric and the resultant militant actions that characterised the student politics Mutambara participated in.

For example, at a graduation ceremony in June 1990, Mutambara — then the president of the Students’ Union — declared in hostile manner to president Mugabe: “we [the students’ movement] do not want a one-party state in Zimbabwe!” A visibly-irritated Mugabe replied: “if you take such extreme views, we will be dismissive of your views”.

A heated verbal confrontation between both leaders ensued, in full view of dignitaries attending the graduation ceremony.

The final section of The Formative Years is a collection of Mutambara’s political views during his studies abroad, which began in the University of Oxford in 1991.

Just as Mutambara was an elected leader in Zimbabwean student politics, he was voted to two student leadership posts during his years as a graduate student in Oxford.

His time in England was followed by research and teaching stints at Nasa and MIT in America, where he took part in various speaking tours at historically black colleges, all the while remaining engaged with the emerging political, social and economic crisis in his Zimbabwean homeland.

Mutambara’s time studying and working in the west brought about some changes in his political beliefs.

He was confronted by hard empirical realities, particularly “the triumph” of liberal democracy and capitalism over communism.

However, Mutambara did not fully embrace “the triumph” of western capitalism, preferring to remain anchored in a Leftist critique of the injustices of the new world order and belief in a renewed Pan-Africanism.

Another hard reality Mutambara faced was UK student bodies’ lack of direct impact on national politics, which was not necessarily the case in Zimbabwe.

Yet the strong accountability and transparency mechanisms and effective organisation of UK student groups provided instructive lessons for the young Mutambara.

On the whole, this book is about one man’s journey of political viewpoints.

A journey in which the idea of justice constantly shadows the author’s steps. The Formative Years will also be of significance to those with an interest in the politics of students’ groups.

There is an increasing hollowing out of Zimbabwe’s national political discourse. The political speeches of Zimbabwe’s national leaders are often imbued with entitlement, threats, self-righteousness, sycophancy and ignorance, not rational compelling argument.

Media coverage of Zimbabwean politics is hardly edifying to boot. Reasoned political ideas appear to matter less these days, making Mutambara’s In Search of the Elusive Zimbabwean Dream: An Autobiography of Thought Leadership a refreshing contribution simply because it takes ideas seriously.

Zimbabwe needs to take ideas seriously again.

Mutambara’s autobiography will be launched at Sapes in Harare on Wednesday.

Miles Tendi teaches politics at the University of Oxford in Britain.

As The Standard celebrates 20 years, it pays tribute to the late Mark Chavunduka, the founding editor of the paper.