“We are mourning the death of democracy in our beloved country.” – Satatement by Andy Flower and Henry Olonga, February 10 2003

As the third session of Zimbabwe’s fifth parliament approached, nearly all the senior leaders of the MDC were facing some charge or other.

President Morgan Tsvangirai, secretary general Welshman Ncube, and secretary for agriculture Renson Gasela were facing treason; vice-president Gibson Sibanda, for “inciting violence”; treasurer general Fletcher Dulini Ncube for Cain Nkala’s murder, and so the list went on.

I, responsible as legal secretary for their defence, was facing my own charge of “discharging a firearm”. And that was just the tip of the iceberg. Many of our MPs and hundreds of our rank-and-file members were facing similar charges.

The legal costs of these cases, together with the civil electoral challenges and Tsvangirai’s presidential election case, were draining the MDC of its resources. This necessitated me travelling to Canada, the UK, US, Germany and South Africa during the parliamentary adjournment to fundraise for the Legal Defence Fund.

Back in the country as the opening of parliament by Mugabe on July 23 2002 loomed, I attended an MDC caucus meeting with all of us feeling besieged. The election had been brazenly subverted and law was being used as a weapon against us.

In that atmosphere, we resolved not to attend Mugabe’s address. We didn’t recognise him as de jure president and the only “peaceful, non-violent way” of expressing that position was by walking out for the duration of his attendance in parliament.

Mugabe duly opened parliament but spoke to a half-empty house. Save for one reference to the fact that 6,1 million Zimbabweans faced “some hardships”, reading Mugabe’s speech afterwards one would think that Zimbabwe was in no trouble at all.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The first motion filed in the new parliament was one proposed by me, condemning the attorney general for his “selective application of the law” and demanding the prosecution of serious crimes. Before we could get the debate underway, though, Zanu PF adjourned parliament to mid-September. They were in no mood to have us document in Hansard all the abuses being suffered.

The figure of six million Zimbabweans facing “hardships” alluded to by Mugabe was in fact a figure used by the World Food Programme at the time, when it warned that this number would soon face starvation.

The figure was bad enough but it was compounded by Zanu PF using starvation as a political opportunity. On July 12 the minister of Home Affairs and Zanu PF MP for Beitbridge, my former client Kembo Mohadi, had addressed a meeting in the province that was facing the greatest threat of starvation. This was Matabeleland South, in which “a clear objective to control NGO feeding programmes was evident”.

Mohadi aggressively told the meeting that because NGOs were there at government’s invitation, they would have to follow government directives and announced that government would “take over” all food distribution. Other, similar reports filtered in, and by late July it was obvious that Zanu PF intended using food as a weapon.

On August 7 the New York Times carried a long op-ed written by me entitled “Zimbabwe’s man-made famine”, with the sub-heading: “Mugabe’s regime will pay any price to keep in power”.

The piece was accompanied by a stark drawing of a maize cob comprised of skulls drawn by award-winning Ukrainian cartoonist Igor Kopelnitsky. Citing the WFP’s six million figure and the WHO’s estimate that 25% of Zimbabweans were HIVpositive, I argued that some 300 000 Zimbabweans could die as a result of the “combination of famine and Aids”. Pointing out that most of our reservoirs still had water, I argued that “had experienced farmers been allowed to plant their crops, Zimbabwe would not have had to import any food at all”. I concluded that Zimbabwe was “becoming a police state” and that “the Mugabe regime may be counting on catastrophe for its own salvation”.

The United Nations-sponsored Earth Summit on Sustainable Development was held in Johannesburg a few weeks after the op-ed was published. Mugabe attended the summit, along with 100 world leaders.

One of the main aims of the summit was to reconcile development with environmental sustainability, with particular emphasis on food security. It seemed that my op-ed, published in a newspaper well read in the United Nations, may have embarrassed Mugabe because when he got back from the summit, he went on another rant.

Soon after Mugabe’s plane touched down at Harare airport on his return from Johannesburg on September 4, he launched into another attack against me: “… whites who have been asking Britain to impose sanctions … do not deserve to be in Zimbabwe.

These like Bennett and Coltart are not part of our society. They belong to Britain and let them go there. If they want to live here, we will say ‘stay’, but your place is in prison and nowhere else. We say no to beggars, no to puppets. We have puppets here in the MDC led by their leader. Even in Parliament they will listen to what their white master, Coltart, tells them to do. We said we don’t want that type of partnership.”

Although Mugabe’s threat was not the first, in the context of all that was going on around me, it was more earnest than ever.

The best form of defence being attack, we arranged for full-page advertisements challenging Mugabe’s statements to be published in the remaining independent newspapers. In particular, we decided to use the telegram Mugabe had sent to me back when I was at university in 1981. Dated August 19 1981, we reproduced the telegram alongside Mugabe’s statement. One of the advertisements asked Mugabe what had changed since 1981.

Several of my black friends came to my assistance. The most poignant was an open letter to Mugabe written by Siphosami Malunga, Sidney Malunga’s son, then a trial attorney on the special panel for serious crimes in East Timor. The letter traced the work that I had done to secure his father’s release from detention and reminded Mugabe of his obligation to respect and protect all Zimbabweans’ rights of freedom of speech.

In the weeks following Mugabe’s statements I had a succession of meetings with advocates Adrian de Bourbon and Chris Andersen, the Zimbabwean senior counsel handling Morgan Tsvangirai’s civil electoral challenge against Mugabe and his criminal defence respectively.

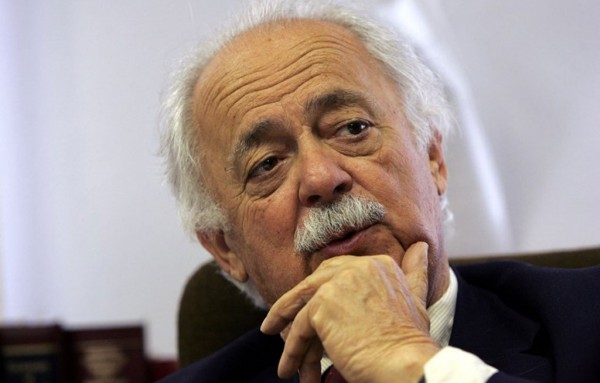

In the meantime, George Bizos had agreed to defend Tsvangirai and I met him for the first time on September 19. Having been in the pressure cooker environment of the Zimbabwe legal system for so long it was deeply encouraging to have Bizos on our team.