The state was dragging its feet on the treason trial so most of our focus was on the civil challenge to Mugabe’s election. We knew he had only won through massive fraud but because of the tight circle of Mugabe supporters who controlled the electoral process, it was important that we get access to what was at the core of the electoral fraud — namely, the voters’ roll.

The Electoral Act entitled all contesting parties to a copy of the roll but all that we had managed to get out of the registrar general’s office was a paper version of it, which was almost impossible to audit. As a precursor to the main case, we had applied to the High Court for an electronic copy of the roll but the presiding judge, Rita Makarau, a person with strong links to Zanu PF, dismissed the case, disingenuously ruling that “copies” in this digital age could not possibly include electronic copies.

Jeremy Gauntlett argued before the Supreme Court on October 1 2002 that the High Court ruling was wrong for three reasons. Firstly, it ignored that the registrar had previously been ordered by a different court to provide the roll on a compact disc, and the registrar could not now renege on this order.

Secondly, “copy” under the Electoral Act clearly meant any form of a copy, just as “writing” in old laws included typewriting. It was common cause that the voters’ roll was stored in electronic form, and could easily be copied on discs. It was pointed out that if the roll was not made available on disc, the task of analysing a voters’ roll containing some five million voters and 120 constituencies would, as the government well knew, be close to impossible. Finally, we argued that the registrar had been evasive and obstructive and was patently acting in bad faith.

Even though the High Court had confirmed that we were entitled to a paper copy of the roll, the registrar had even refused to provide us with that copy. In a remarkable feat of jurisprudential gymnastics, the Supreme Court, under Chidyausiku, contrived to find reasons why we should not receive an electronic copy of the roll. To this day, it remains a major issue which dogs the electoral process in Zimbabwe.

In among the various legal proceedings was the ongoing need to use parliament as a forum to expose the ongoing horrors within Zimbabwe.

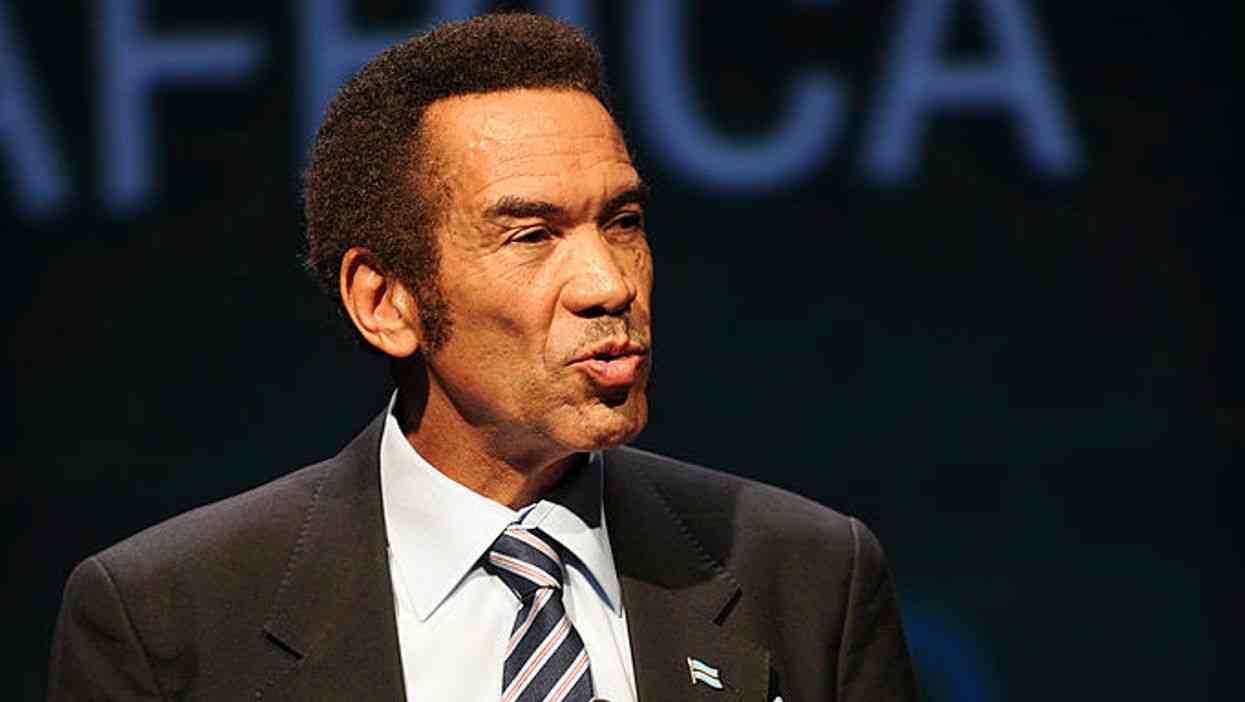

On October 15 2002, I debated a motion on the ill-treatment, including torture, of suspects and ordinary members of the public, by the Zimbabwe Republic Police. Ironically, my address had to be directed to the speaker, Emmerson Mnangagwa — one of the key architects of the Gukurahundi which resulted in wholesale torture. I commenced by acknowledging that the root of torture was to be found in the methods used by the British South Africa Police (BSAP).

I pointed out that in the early 1980s, many former members of BSAP had remained in the police force and were responsible for much of the torture. I reminded the minister of Home Affairs, Kembo Mohadi, that I had represented him in the case, concluded on July 4 1986, in which we had obtained on his behalf $14 000 worth of damages after he himself had been tortured by the police.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

This caused quite a stir and the interjections started to flow freely, especially from the minister of Justice, Patrick Chinamasa, Despite these interjections, I exposed several current examples of police using torture and concluded by arguing that Amnesty International’s 12-point programme for the prevention of torture should be implemented.

I pointed out that the International Convention against Torture had been ratified by all our neighbours and if Zanu PF persisted in its refusal to ratify the convention, it could be argued that it had acquiesced or condoned the ongoing acts of torture. Not surprisingly, both the speaker and the Zanu PF front bench studiously ignored my arguments; if anything, the incidence of torture grew in Zimbabwe during the years that followed.

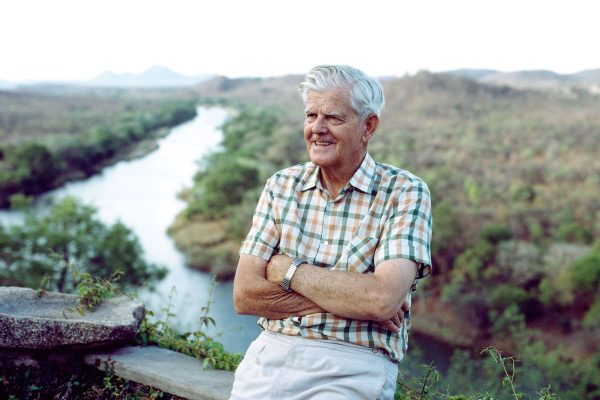

Shortly after this debate, we witnessed the end of a chapter in Zimbabwe with the death of one of my heroes, Sir Garfield Todd. His wife Grace had died the previous December and they were such a team that I think he lost the will to live. On Sunday, October 27 2002 thousands of us congregated at Dadaya Mission again to pay our last respects.

As Judith Todd wrote subsequently, the event was more like a wedding than a funeral because it was a celebration of a person who had had a consistent vision for many decades of a moderate, tolerant and democratic Zimbabwe.

At the urging of Eddison Zvobgo, at the graveside Judith Todd read out a personal letter to her sent by Queen Elizabeth, which caused a rumble of contentment throughout the massive crowd. I was left wondering what Zimbabwe might have been had Garfield Todd not been deposed in February 1958.

On my return to Bulawayo I received a sharp reminder that Zimbabwe was some way off Todd’s vision of a benign state. On the drive back from Dadaya the brakes on my vehicle appeared to be playing up and so I had it checked. It was discovered that one of the brake lines had been deliberately severed. It was the first, but not the last, attempt on my life in the ensuing months.

Although I had been threatened several times before, this was the first actual attempt; I was immediately forced to increase my security, which included a new routine of checking my brake lines after any of my vehicles had been left in a public place.

Fortunately, I was due to fly abroad again, which provided a welcome break from the increased pressure brought about by this unwelcome discovery.

At the end of October, I visited Canada and the United States. The main purpose of this trip was to address a meeting of Parliamentarians for Global Action in Ottawa on the role of parliamentarians in developing the recently-announced United Nations principle of the “Responsibility to Prevent”. The opening address at the meeting was delivered by Bill Graham, the Canadian foreign minister, who spoke on the topic “The State’s Responsibility to Protect as the New Governing Principle of International Affairs”.

The principle, first developed by Kofi Annan, held that where a population was facing serious harm as a result of state failure, and the state in question was unwilling or unable to act, the general and historical principle of non-intervention yielded to an international responsibility to protect.

There was broad support for the notion and my speech on the topic was supported by positive interventions from MPs from Tanzania, Senegal, Burundi and Panama. This new principle potentially gave us a very useful lever to argue that the international community should not just sit aside and observe anarchy taking place within Zimbabwe.

From Canada I flew to Washington for another series of meetings, including one with Kofi Annan and US Secretary of State Colin Powell on 12 November.

Walter Kansteiner III, then assistant secretary of State for Africa, set up the meeting on the sidelines of a UNA-USA International Visionaries dinner. Having just had the benefit of hearing the Canadian Foreign minister’s views, I argued that the responsibility to protect doctrine should be invoked in respect of Zimbabwe.

I stressed that I was not advocating any form of invasion but believed that the United Nations in particular should play a more active role in trying to resolve the Zimbabwean crisis. Continuing a theme I had first raised in the New York Times op-ed, I argued that there needed to be more bilateral engagement with the South African government.

Once again, I expressed the fear that the Zanu PF regime was using food as a weapon. Both men were deeply sympathetic towards our plight but were pessimistic about what could be achieved to bring about change without more regional support. I got word later that evening that Annan had agreed to raise the issues in the UN.