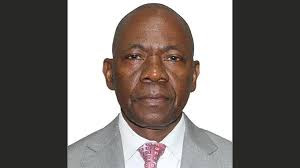

Watching Chief Justice Malaba deliver judgment on the election results impasse last week was uncomfortable and painful. It was also very troubling, to me. After 38 years of political freedom, we are still captured by the vestiges of colonialism.

the sunday maverick with GLORia NDORO-MKOMBACHOTO

That scene, a legal tradition in Zimbabwe, where judges wear long horse hair curly grey wigs, remains etched in my mind. It shows that while the colonial project ended some 40 years ago in Zimbabwe, its remnants are going to be with us for a long time to come.

Dipti Sawant, an Indian advocate with the Bombay High Court writing for Quora in 2015, advises among other things that some of the several reasons behind having a standard court dressing style, include the following:

- Originally court dress was designed to distinguish members of the legal profession from other members of society. l Brought authority, formality and dignity to court proceedings.

- It emphasises on the objectivity of the law and deflects personal attention from the judge.

- Wigs, especially, were supposed to bring anonymity to the judge.

- Since in earlier times the people were discriminated on the basis of colour and ethnicity, the standard form of wigs removed bias and impartiality on the part of judges; that judge did not belong to any one colour or creed but was an impartial, unbiased human being deciding the case.

- Moreover the anonymity helped the judge to be less recognised outside the court, thus helping them hide the identity.

But in my mind, all these reasons are no longer valid for India, Zimbabwe and any other Commonwealth country previously colonised by the British. I am not even sure if this was valid from the outset.

Tina Marshall, an American Attorney writing for the same newspaper in 2017, argues that in the days before basic hygiene and cleanliness took hold, the rich shaved their heads to discourage lice infestations and wore wigs to hide their baldness. This quickly became a status symbol as only the wealthy and educated were able to afford these horse hair wigs like the ones lawyers and judges are still required to wear in many situations in the UK and other Commonwealth countries. This practice somehow became associated with the practice of law and has stuck. Recently, the wearing of wigs has become less common in the UK, much to the delight of lawyers and judges because of their expense and itchiness.

The point is, rules and regulations are made by people and can be reviewed and abolished by the same people.

It is the same unresolved argument going on in some of the churches where the mothers’ union wears uniform. In the United Methodist Church of Zimbabwe, the mothers’ union members (of which I am), wear an outmoded and unfashionable red and royal blue uniform with a white doek that must be worn in a particular fashion. Their counterparts in the US where the church was founded do not wear this uniform. The excuse for not changing and modernising the uniform has always been around a flimsy excuse around the fact that the founding mothers of the mothers’ union, like the late Amai Chimonyo, prayed for the uniform and therefore the uniform is sacrosanct and untouchable. This closely held view essentially undermines the prayers of the current cohorts of mothers’ union members in the church for their prayers can never be good enough for any uniform change management intervention.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

What does decolonisation mean?

In a nutshell, decolonisation means the undoing of colonialism. It represents dismantling of western centred institutions, systems, symbolism and standards within the political, economic and social spheres.

Decolonisation is the meaningful and active resistance to the forces of colonialism that perpetuate the subjugation and/or exploitation of our minds, actions, bodies, and lands. In our situation, decolonisation out to be replaced by Africanisation, which is the ultimate purpose of deconstructing and overturning the colonial structure and mentality while fully realising, appreciating and practicing indigenous Africanism that was interrupted by the arrival of settlers some 500 years ago. The least we can do is to Africanise and at best Zimbabweanise.

First and foremost, decolonisation must occur in our own heart, minds and soul. The Tunisian decolonisation activist, Albert Memmi, wrote: “In order for the coloniser to be the complete master, it is not enough for him to be so in actual fact, he must also believe in its legitimacy. In order for that legitimacy to be complete, it is not enough for the colonised to be a slave, he must also accept his role.”

The first step toward decolonisation, then, is to question the legitimacy of colonisation. Once we recognise the truth of this injustice, we can think about ways to resist and challenge colonial institutions and ideologies. Thus, to Africanise/Zimbabweanise is to be active in understanding and practicing African knowledge systems and ideologies. Why do we need to Africanise/Zimbabweanise?

Steve Biko once remarked: “The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” Biko was the cornerstone and embodiment of the South African liberation struggle. Incomparable to anyone in the world, Biko urged black people to define and discover themselves, their history and their values. For him, it was the only logical and reasonable way of finding their self worth.

Self-worth is defined as “the sense of one’s own value or worth as a person. Self-esteem is defined as “the confidence of one’s own worth or abilities”. Self-respect is defined as “the pride and confidence in oneself”. The colonialism project stripped Africans off their self-worth, self-esteem and self-respect. That is why to this day, Africans across the spectrum, benchmark themselves against their former colonial masters. Hence, for example, the failure by the judges to do away with those hideous, horse hair, itchy wigs!

Without self-worth, Africans have got no one but themselves to blame. Without self worth, Africans will always look outwardly for solutions completely oblivious to the fact that what they currently possess, their humanity, people, their mind power and natural resources are sufficient conditions for home grown prosperity without necessarily seeking help from those who benefitted from colonialism and continue to do so today. That is why one of the key reasons why the decolonisation project is long overdue.

In many African countries, blacks remain poor and powerless long after those countries gained political freedom. The majority do not own land, are homeless and struggle with dreadful chronic diseases, so do not have access to clean water and electricity and are forced to believe that they must be grateful because political freedom was attained. Across Africa, including Zimbabwe, political freedom has benefitted a few who took over where the colonial project left off.

After 27 years of incarceration by the oppressor, Nelson Mandela refused to wear a suit, a dress code introduced by colonialism across the world because it is said, “to represent my people and their diverse cultures.” Fashion designer Marianne Fassler also argued that, “by wearing a shirt, Mandela was telling us that he was going to change all the institutions, all the ingrained, meaningless protocols, break down all the barriers between us and be accessible.” This anecdotal example while seeming simplistic, demonstrates that unless you become uncomfortable with the damaging effects of the colonialism project, there will be no consciousness nor room for Africanisation to take place. Kenyan intellectual Ngugi wa Thiong’o, in his book Decolonising the Mind, describes the “cultural bomb” as the greatest weapon unleashed by imperialism:

The effect of the cultural bomb is to annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves. It makes them see their past as one wasteland of non-achievement and it makes them want to distance themselves from that wasteland. It makes them want to identify with that which is furthest removed from themselves; for instance, with other peoples’ languages rather than their own. It makes them identify with that which is decadent and reactionary, all those forces that would stop their own springs of life. It even plants serious doubts about the moral righteousness of struggle. Possibilities of triumph or victory are seen as remote, ridiculous dreams. The intended results are despair, despondency and a collective death-wish.

In the Decolonisation Handbook entitled, for Indigenous Minds Only, various indigenous scholars, writers, and activists have collaborated as they reflected on the understanding that “decolonising actions must begin in the mind, and that creative, consistent, decolonised thinking shapes and empowers the brain, which in turn provides a major prime for positive change.” Editors, Waziyatawin and Michael Yellow Bird submit that, “…undoing the effects of colonialism and working toward decolonisation requires each of us to consciously consider to what degree we have been affected by not only the physical aspects of colonisation, but also the psychological, mental, and spiritual aspects.” For meaningful Africanisation/Zimbabweanisation to be realised, we first need to unpack and comprehend the systematic ways used to disrupt the African agenda. This understanding is crucial because you cannot defeat what you do not know. And as we discover, install and institutionalise African ideologies and knowledge systems, it is wise to be mindful that the pathway to self-determination is within us, always.

Gloria Ndoro-Mkombachoto is an entrepreneur and regional enterprise development consultant. Her experience spans a period of over 25 years. She can be contacted at [email protected]