Former Finance minister Tendai Biti’s presentation at the just-ended hearings by the commission of inquiry into the August 1 killings of protesters by the army was acknowledged by many as a timely reminder of the need for genuine national healing in Zimbabwe.

Editorial Comment

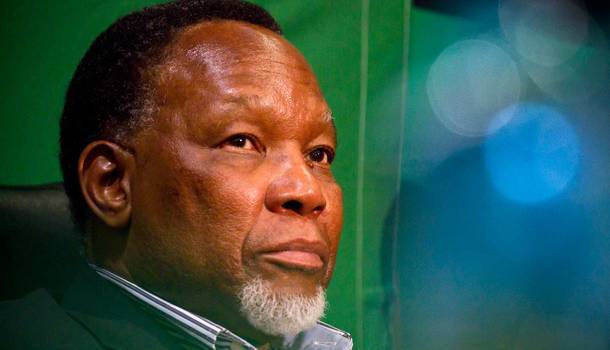

Biti, who is now the MDC deputy chairman, told the commission, chaired by former South African president Kgalema Motlanthe, last week that the tragic events where soldiers opened fire on unarmed protesters were not an isolated occurrence.

Zimbabweans have suffered grotesque violence since pre-colonial times, and unlike in countries like South Africa where a truth and reconciliation commission was set up to deal with conflicts of the past, this country has never confronted its ugly history.

In fact, during former president Robert Mugabe’s 38-year rule, violence became a tool often used by the ruling party and state security agencies to thwart dissent. The perpetrators of violence were rewarded while victims were punished twice as they were denied justice.

Jim Kunaka, a former Zanu PF militia leader, also told the Motlanthe commission that during his time in the ruling party he was at the forefront of violence perpetrated against the opposition and he enjoyed full protection from state security agents.

Kunaka was confirming a publicly known secret that there was wanton selective application of the law in Zimbabwe under Mugabe.

From the 1980s massacres in Matabeleland and Midlands to the 2008 political violence where the military was also implicated, justice always eluded victims.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

It was against this background that Zimbabweans welcomed President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s appointment of the Motlanthe commission, which has a sprinkling of respected Africans whose skills in resolving conflicts elsewhere in Africa could have helped Zimbabwe to exorcise its centuries-old problem of violence.

There were serious misgivings about the appointment of Zanu PF activist Charity Manyeruke and July 30 presidential candidate Lovemore Madhuku, but many Zimbabweans were still willing to give the commission a chance.

However, events of last week, where the commission hastily ended the hearings before getting testimonies from scores of people that were directly affected by the August 1 shootings, dashed many people’s hopes that a breakthrough would be made in efforts to heal a deeply wounded nation.

The 15 witnesses submitted their harrowing evidence through the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum, but were inexplicably sidelined by the commission.

Instead, dubious victims aligned to the ruling Zanu PF and state security agencies were given unfettered access to the commission.

As if that was not enough, the commission submitted its preliminary findings to Mnangagwa a couple of days after concluding the public hearings.

Therefore, it would not be further from the truth to conclude that besides being a waste of scarce resources, the commission was a charade and a missed opportunity to finally address one of the major challenges drawing Zimbabwe back, which are unresolved conflicts and a damaged national psyche.