BY KEN MuFUKA

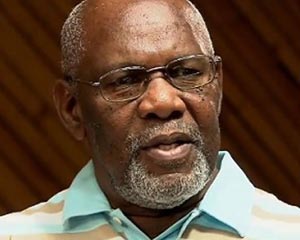

The passing of Dumiso Dabengwa comes as a reminder to all of us that our dreams of a peaceful and prosperous Zimbabwe were betrayed from the beginning.

The fact that we were all conned by the greatest artist on earth, Robert Mugabe, for the last 40 years, speaks more to our gullibility as a race than to his craftiness.

Dabengwa and I belonged to the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu). From its inauguration in 1963, our leadership under Joshua Nkomo was never disputed.

I met Dabengwa at the Commonwealth Conference in Jamaica in 1963.

Though I was the smallest of the saints, I held an enviable position as representative of Zapu in that far-flung island.

I was instructed by Edward Ndlovu in Lusaka to scout out sympathisers for the Patriotic Front.

Zanu had no representative in Jamaica.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

It was a great honour for me when Dabengwa visited my house.

I remember that I raised two issues. We assumed, as indeed the Frontline states leadership assumed, that Joshua Nkomo was the senior leader of the Patriotic Front and that Mugabe would fall in line.

While Nkomo treated me with kindness and respect, making me feel that my small contribution to Zapu (and the sacrifice — my position was without pay) was worthwhile, Mugabe refused to see me, pretending to be engaged in some studious toil.

I also raised the issue of ethnic rivalries. Dabengwa, who had trained in the Soviet Union, was ahead of his time. People are what they identify with. For instance, Kalangas identify with the Ndebele.

This idea was 50 years ahead of time. People can have more than two identities, one local and another national.

I also visited with Ndabaningi Sithole, who, having been thrown out of Zanu, had no hotel arrangements. So he stayed at my house.

But more to the point, even as we conversed in my house in Jamaica, and even as Sithole had warned us, that Mugabe was a bureaucrat, Mugabe was already putting in place mechanisms to undermine that unity.

My highest honour came when I carried Nkomo’s bag as he went to see Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley.

Nkomo was a master of human relations. He thanked Manley for giving me a place in exile, but hoped that exile would soon end.

As for Dabengwa, he returned to Lusaka to carry out the liberation struggle.

But we were shocked when just two weeks before the elections of 1979, Mugabe separated Zanu from the Patriotic Front.

We felt betrayed and shocked.

The dream, which I had shared with Dabengwa in Jamaica, that tribal fissures were a thing of the past, had been betrayed.

We in Zapu were true nationalists, as Dabengwa had explained to me.

Zimbabweans were free to adopt different identities, while the supra organisation, Zimbabwe, was representative of all nationalities.

We know for certain that there was opposition within Zanu to this direction.

General Josiah Tongogara, Dabengwa and Solomon Mujuru were in general agreement.

Mujuru was younger, 28, and was conned to abandon this path by promises of a high position.

Tongogara’s life was forfeited on the eve of his return to Zimbabwe at Christmas 1979.

The government of national unity in 1980 was a charade. In October 1980, investigative reporters revealed that Mugabe had been in negotiations with the North Koreans.

A purely tribal army, whose only aim was to crush the Ndebele and Zapu, was in the offing.

Zapu veterans had in good faith pooled their pensions and bought 22 farms for resettlement.

The success of these farms contradicted Mugabe’s dream of a communist-style “long fields.”

The false accusations against Dabengwa and Lookout Masuku and the murder of Nkomo’s bodyguards and ransacking of his house brought mirth to Mugabe’s followers.

I was on a Shu Shine bus No 84 in September 1983 to see old friends in Bulawayo when we were stopped somewhere west of Zvishavane and all passengers with Ndebele names asked to leave the bus.

To this day I have nightmares as to what happened to them. When I witnessed a night camp fire at Esigodini and inhuman cries coming from the orange grove where beatings were going on, I quietly arranged to return to the US.

I too felt betrayed.

Little did our brother sinners in Zanu realise that by cutting off Bulawayo and Hwange, the employer of 15 000 railway men, and the producer of thermal power, they were oblivious to the destruction of commerce, of which Bulawayo was the centre.

The greatest betrayal, which was self-inflicted, was the surrender of Zapu and its disbandment.

Dabengwa and many others were opposed to the disbandment of the party.

I was on Dabengwa’s side, but was only a carrier of Nkomo’s bag. I had no influence.

That, as was the inclusion of the Movement for Democratic Change in 2009, strengthened Mugabe’s rapacious policies.

The great betrayal came in 2007. Dabengwa had agreed with Solomon Mujuru to support Simba Makoni.

Both these stalwarts had a genuine fear of the MDC as a surrogate colonial project.

Mujuru, according to my research, was called and his “alleged” corrupt activities read to him.

While Mujuru failed in the hour of most need, his activities outside the party led to his murder.

While Mugabe’s rapacious activities drove 3,5 million economic refugees into exile, it created a class of Zanu stalwarts who benefitted from what Professor Steven Hank has called a “criminal state enterprise”.

This “casa nostra” (criminal family) was capable of defending itself against intruders.

In my last conversation with Dabengwa, he pointed out to me that the manpower drain in Matabeleland to South Africa was a powder keg waiting to explode.

Mujuru and Dabengwa had foreseen this negative development accelerating, especially with the rise of Grace Mugabe, an ignoramus, to a position of influence.

Jonathan Moyo has pointed out that Mugabe was apprised of this growing resentment and the possibility of a coup.

The murder of Mujuru was messy.

My research shows that poison was attempted on Mai Shuvai Mahoffa (a friend of mine), but results were not neat.

To cut a long story short, the major players were identified and the “muti” was applied.

The most effective of this muti, is nicknamed the Litvinenko, after a Russian dissident, who turned blue.

Dabengwa lived among us, yet we did not appreciate his saintly qualities of perseverance in the face of wickedness all around him.

Peace be with my brother on his next journey.