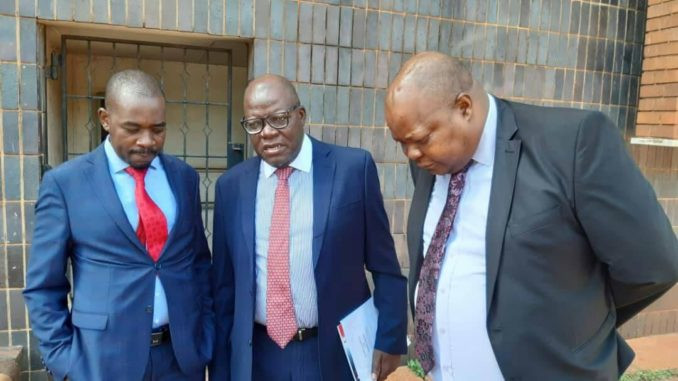

Celebrated Toronto-based paediatric cardiologist Norman Musewe opened up about his Christian faith, medicine, science, purpose, philanthropy and life in the diaspora in the latest episode of In Conversation with Trevor.

Musewe (NM) told Alpha Media Holdings chairperson Trevor Ncube (TN) in the wide-ranging interview why he returns to Zimbabwe regularly to help a clinic where he was born in Harare’s Highfield suburb. Below are excerpts from the interview.

TN: Dr Musewe, you are a world-class paediatric cardiologist based in Toronto, Canada, a Zimbabwean born in Highfield at Highfield Polyclinic. What has it taken to be where you are?

NM: I suppose it would be good to start at the beginning. The beginning was my parents.

I was born in Highfield because we were living in Old Highfield right across the clinic and I grew up in Highfield.

I am the first of a family of seven, two girls and five boys.

I used to walk to Chipembere Primary School every day. My mother taught me my first grade, sub A, and I was left out of the group because when she picked her students I was not quite six (years old).

I was unable to touch my ear. So there were a few short to fill her class, so they asked who you want to add in your class, I was the obvious choice.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

I used to walk to school and sometimes my mother would give me a ride on her bicycle back and forth and she was a hard task master.

I had no excuse that I didn’t do my homework. So I learnt early values from her.

She had the ear of other teachers and even as I went to Grade One, Grade Two and Grade Three there was no way I could say things that she did not know about. She knew more about it than I did and I think that kept the boundaries tight for me, for which I’m grateful.

Some of the teachers were just amazing, encouraging.

I remember Mr Mukome in particular and there were two of us competing for first place. This young man and myself, I never beat him.

I was always second, but that kind of encouragement from my mum, my teachers gave me the desire to do well because my mother told me about the story of Washington.

He was an African American looking for a place in a college and they put him in a room after an interview asked him to clean the room.

He went next door and when they came back, they went to the obscure places to make sure he had dusted the cupboards and so on and they could not find a speck of dust and my mother said this is a lesson in life, whatever you put your hands to doing, put everything into it no matter how small or how big it is TN: And your dad?

NM: My father also was a teacher. He was a principled teacher, a loving father. He was very sacrificial.

His goal was to educate us to the last penny that he had, to the extent that he denied himself things in life.

So I was grateful because I saw the sacrifice that my father made.

I saw him walking back and forth to school when he could have bought a car.

He used to teach carpentry and we would walk to his office and he would say to me, my son, what do you see up there and I would say the sky and he would say, the sky is the limit.

I can’t explain how inspiring it is to hear it from your own father.

TN: And those values stayed with you? So you are practicing now in Toronto, what has been the journey like you moving from Highfield to finding yourself in Toronto?

NM: In Standard Five I went to Bernard Mzeki Primary School and I went to Bernard Mzeki College, which was just across the road for Form One and Two and by the wisdom of my parents they moved me to Goromonzi.

I can elaborate on that if you wish. At Goromonzi I did my Form Three, Four, Five and Six.

I went to the University of Zimbabwe, then the University of Rhodesia, in 1970.

I graduated in 1975. I broke my training for a year to go to Birmingham University to do a Bachelor of Science.

TN: University of Rhodesia then was a college of the University of Birmingham.

NM: Exactly and they took the top two or three students and I did physiology.

TN: You happened to be in the top two?

NM: Yes, I was, that’s how I got the scholarship to go there for a year, which taught me a lot and exposed me to new things and actually gave me a new desire, passion.

Having seen what I saw, I did research in physiology for a year and came back and finished my degree. I then worked for two years at Mpilo Hospital.

Now I think that’s where my passion for paediatrics started because there was a doctor called Glenn Jones.

I consider him an amazing paediatrician. I watched him work with children and I learnt so much from him and I said I want to be like that.

TN: He is one of your role models?

NM: Yes, he would be. Unknowingly, I don’t think he even knew that he was influencing me that much and I think that’s the characteristic of good role models, they don’t know what they are doing.

He was just excellent and after two years at Mpilo I was committed to paediatrics for the rest ofof my life.

There was no such question about it. I don’t know how, but I think he played a central role. Then I moved to England.

TN: I think it’s an important story because you didn’t voluntarily go to England. You were forced by circumstances, would you describe to us what forced you to leave the country?

NM: In my second year of paediatrics, which was in 1977 at Mpilo Hospital, in October, I received from the Ministry of Defence call-up papers to go and work for the ministry as a doctor.

TN: To work for the army basically?

DM: There were a few of us who were called up, one of my friends went to Mozambique and I went to Botswana. I simply had to go.

I couldn’t countenance myself working for the then regime that was in power.

So they put me in an impossible position and I quickly gathered everything and sent it home to my parents in Highfield and said bye bye.

It had major implications because I was accosted by the army when I was crossing the border and they asked me where I was going and I made up a story and to my surprise they believed the story.

I went to Gaborone. I had taken the precaution of applying for a course in Scotland, a postgraduate course, and that led me into Johannesburg.

I flew to London and on the 1st of January 1978 I was in the air and I said Hallelujah.

I was so happy because I was so terrified of the possible consequences and that’s what started my journey in England.

TN: The most important thing there for me is you were forced to make a choice, a choice which has impacted on you almost for a lifetime, which speaks to purpose, which speaks to who orders your steps to get you to where you were, do you want to talk to us about that?

NM: As I was on the journey to Botswana, I started to think through life. There are moments like that when you are in a crisis and I had the sense of guilt that I was the first born of the family and I was almost abandoning my family.

I laboured with these thoughts quite a bit and I suppose somewhere something started happening in me that started saying why and how and, of course, much later on I realised that just in the same way Joseph went into slavery in Egypt, God had a purpose (for me) and I didn’t realise it.

TN: You didn’t make a choice, it was made for you. So you have left home, but you still remain connected to the place where you were born which is Highfield Polyclinic. You come here almost every year to lend them support. Can you explain to us what has motivated that, what’s the nature of this work that you give to Highfield Polyclinic?

NM: Perhaps I could start by saying this dislocation from my birth place and unwilling dislocation took me on a journey, which I would like to describe in three dimensions.

I’d say the first dimension was the backward look and the second forward look and there is a tension between those two, which I think is a tension in everyone who goes to the diaspora.

It’s a good tension, but it must be moderated by your worldview and that’s where the third dimension comes in, the looking up.

As I felt this tension between the backward look, what is back home and the forward look, why am I here, what am I going to do here?

That led me in some sense to start reflecting inwardly and looking upward and saying there must be purpose to all these because the diaspora experience is not a bed of roses as we know.

I think it’s true that progression — that upward dimension looking to my Creator and seeing His purpose in my life — that then ended up into reflecting inwardly to say what then is my purpose, is it enough just to be a cardiologist in Toronto and treat patients there? Is it enough to just raise my family, is it enough to just work within my congregation, what’s my circle of influence? And that backward tug was a very powerful tag of relatives and friends TN: I want to learn to hold that thought that am I right, that what you describe — search for purpose, search for meaning, why am I here?

NM: It’s a powerful question and I think every human being asks that question at some point rather and, of course, there were obstructions, obstacles were the grind of just being in the diaspora — the blocks, the walls that you have to go over, the challenges just sometimes push you down so much that you lose hope. TN: I want to focus on something important, raising the grind of being in the diaspora, please unpack it for us, what does it mean?

NM: It means a few things. I think first it means just making a livelihood.

There are lots of us who get out there, you find out your qualifications are not what you thought they were.

You have to sit a whole lot of exams and there are many requirements and that alone I had to re- write my medical exam when I went to Canada.

The actual qualifying exams and on top of that it’s getting into the system, making headway, there are obstacles, but in particular in England some of them are racial and those are the most tough ones because you know you can do it but you are denied the opportunity and even at one stage I couldn’t find jobs in England.

I had to do manual work to make sure that I could make a little bit of money.

TN: But here you are successfully rendering help to the place that witnessed you coming into this world, describe that connection, that umbilical connection between you and that place in Highfield.

NM: Because of that desire to make meaningful change and because I saw children in Toronto getting excellent care, I asked myself a question: What about in Highfield, what about where I was born, what’s going on there?

So I made a few trips just to look. One of my first trips when I came to Highfield, I went to the polyclinic and the remarkable thing is that the bed on which I was born 65 or 60 years ago, that was about 10 years ago, was still the same bed in there, in the same ward.

I said to myself this cannot be, something has to be done, something has to change.

So at that time with the assistance of the then mayor Mr [Muchadeyi] Masunda in Harare, I said what can we do and he said look primary care is being provided at the polyclinic level, perhaps you should focus your efforts there.

I said fine and at that time we were running a small company in South Africa.

So we bought hard equipment, incubators and so on for the resuscitation of newborn babies and it’s still there and then having an affiliation with an organisation called Help Partners International, which is based in Canada, what they do is they collect medication from pharmaceutical companies and they become the portal to provide for us.

So the affiliation allowed us to ship or bring medication periodically to the clinic, in addition to other things that are always asked for, blood pressure machines, glucometers, even pens and paper, so that’s what we’ve been doing.

TN: Talk to me about your looking upwards looking internally, where has that looking ended up, have you arrived at it?

NM: One of the amazing things for me is that God would love each human being so passionately, but it’s unreal, nothing like anything on earth and when I recognised that, God I’m not just a number, not just a random individual, God thought about me before I was even a born, appointed me to be born at Highfield Polycclinic on the 6th of April 1950, no accident, everything planned and then I discovered Jesus Christ.

God in man dying on the cross and I said to myself if God loves me so much that He would send his son just for me alone even for me, it just blew all my circuits.

It melted me inside which then God started remoulding me into a new creation as we know and that new creation that I have become tells me one of the scriptures that says the love of Christ compels us, you cannot just sit back.

You are asking the question, yes, I am my brother’s keeper, that I ought to do.

I belong to a vibrant congregation in Toronto called the People’s Church.

We are very involved in those areas where I believe God’s heart is — the oppressed, the poor, the aliens, the widows, the orphans that’s where my heart is. TN: Reading around, I realised that justice and human dignity are things that are very important to you. Perhaps part of your purpose and that passion obviously comes from the journey that you walked with your Creator. Outside medicine you have ended up being appointed chairman of the board of the International Association of Refugees in Canada, talk to us about that project and what you do, what you are involved in.

NM: The (United Nations Commissioner for Refugees) puts out data that says, if I’m not wrong here, that about 60 million people are migrants.

They are moving either internally or externally crossing borders or looking for sanctuary outside or far from where they were born for all sorts of reasons.

Number two, in Toronto, we receive at least a quarter of a million refugees every year.

Number three, I also recognise that I was once a refugee because as I migrated I saw other people migrating perhaps using different paths but going through the same experience.

We said in our congregation we have to help, these are people who ordinarily find doors closed, they are rejected, they get the worst, they are at the bottom of the pile.

So I personally with the church provide refugee homes that are in Toronto where we receive refugees from all over the world and I must say 5% of them are from Africa and so we get interaction. It’s amazing when they see another African who sees himself in the diaspora who says I know what it’s like to transverse borders unwillingly for whatever reason, I have the duty to comfort you.

While the government can provide social welfare, social assistance and health care, there is a gap and the gap often is that emotional, spiritual, traumatic experience that needs to be answered by walking with somebody by loving somebody, by befriending them and letting them speak out and sharing the experience.