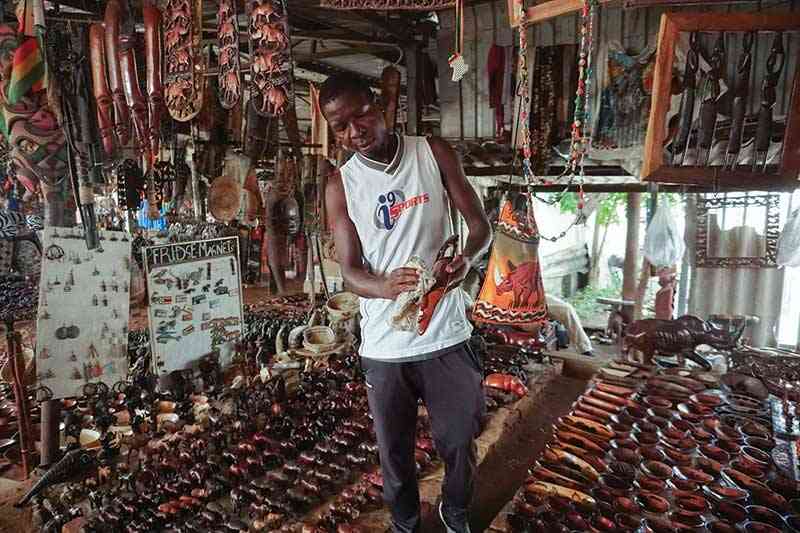

INSIDE the Sinathankawu arts and crafts market in Victoria Falls, Amon Kunda polishes a sculpture as he waits for customers.

The market is lined with stalls that sell beaded work, wood carvings of various sizes and textures, and other souvenirs.

The wares are neatly arranged, each piece the evidence of a skilled hand. Other traders — some of whom are craftsmen themselves — sit in their stalls and polish their products.

Like Kunda, they are waiting for customers, mostly local and international tourists who visit the city for attractions such as Victoria Falls, one of the largest waterfalls in the world. These attractions guarantee a ready market. But today, only a few customers have visited.

Kunda lives in Chinotimba, a high-density suburb in Victoria Falls known for its resorts, and has had a shop in the arts and crafts market for 17 years.

“I have built a home and put my two boys through school from selling arts and crafts,” says Kunda.

“But hotels and lodges have stolen our business.”

Local arts and crafts traders in this tourist hotspot decry increasing competition from hotels and lodges, which they say is not only stealing their heritage but denying them a livelihood.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Traders contend the competition worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, when movement restrictions meant that tourists — both local and international — stayed in their hotels, prompting hotels and lodges to sell souvenirs directly to visitors.

Even after restrictions eased, hotels didn’t stop, so now, fewer tourists buy directly from informal traders.

“People were cautious of moving around,” says Nguquko Tshili, secretary-general of the Adam Stander Traders Association, an association of arts and crafts businesses in Victoria Falls.

“They bought curios at hotels and lodges where they were staying.”

Between 500 and 600 traders have been affected in Victoria Falls alone, Tshili says.

For arts and crafts traders like Kunda, the industry is their lifeline, and they make up a significant part of its infrastructure.

Arts and crafts products ranked fifth of 13 products and services, according to 2018 government data, in terms of percentage of products consumed by tourists, such as food and beverage services, accommodation services and travel agency services.

Foreign visitors spent 12,1% of their total expenditure on arts and crafts that year.

The conflict between hotels in Victoria Falls and arts and crafts traders is about more than just loss of business, says Daves Guzha, a renowned arts expert and theatre producer based in Harare.

Guzha worries that if this line of business doesn’t remain viable for traders and they lose out to big hotels, they will lose more than a lifeline. They will lose their culture.

Rayton Ncube has spent 22 years in the curio trade; it’s his identity.

“Hotels and lodges should stick to their core business of offering accommodation to tourists and not interfere with our business, which is our sole source of livelihood,” says Ncube, a father of four.

The solution, Ncube says, is for the municipality to ensure that businesses stick to providing the services for which they are licensed.

“Our biggest challenge is that there is no law or clause in the local laws that stops hotels and lodges from selling artifacts,” says Tshili, the secretary-general for the traders’ association.

“We are currently in the process of lobbying the municipality to include a clause that protects our businesses.”

He says the clause will bar hotel operators from selling curios.

Zimbabwe’s arts and crafts exports reached about US$10,5 million in 2019, mostly destined for South Africa, Europe and the United States.

Local arts and crafts traders say hotels and lodges are not only stealing their heritage but denying them a livelihood.

Mandla Dingani, spokesperson for the Victoria Falls Municipality, says businesses are free to offer whatever service they wish, if they are licensed for it.

“[The municipal] council licences according to services rendered by the applicant, and in this case, the hotels in question have been duly licensed for their services and crafts shops domiciled in their areas of operation as well,” Dingani says.

Licences are governed by the Shop Licences Act, which doesn’t discriminate against any company’s intention to venture into a type of business, Dingani says.

“In the same spirit, the local authority is not prohibited from licensing hotels which intend to venture in the selling of artifacts.”

Brian Ndlovu, business manager for Teak Lodge in Aerodrome, a low-density suburb in Victoria Falls, says the municipality licensed the hotel to sell crafts in 2016.

In most cases, he says, their clients prefer a one-stop shop. He adds that between 2014 and 2015, tourism boomed. The lodge saw it as an opportunity to expand its business.

Environment, Climate, Tourism and Hospitality minister Nqobizitha Mangaliso Ndhlovu says the current conflict is in the jurisdiction of the municipality, which is responsible for issuing trading licences.

But he sees the arts and crafts sector as a part of tourism that makes a significant contribution to the country’s economy.

“As a ministry, we make sure that we support the sector the best way we can,” he says.

Tourism in Zimbabwe has made major contributions aside from employment, according to a study published in the African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure.

For example, international tourists spend foreign currency, which boosts Zimbabwe’s currency reserves.

Tshili says the traders’ association is in the early stages of drafting a proposal to the municipality. Dingani confirms that the Victoria Falls Municipality has not yet received an official complaint from local traders.

Meanwhile, he urges hotels, craftsmen and traders to engage in dialogue and figure out the best way to work together — “from the production line right up to the selling point.”

— Global Press Journal