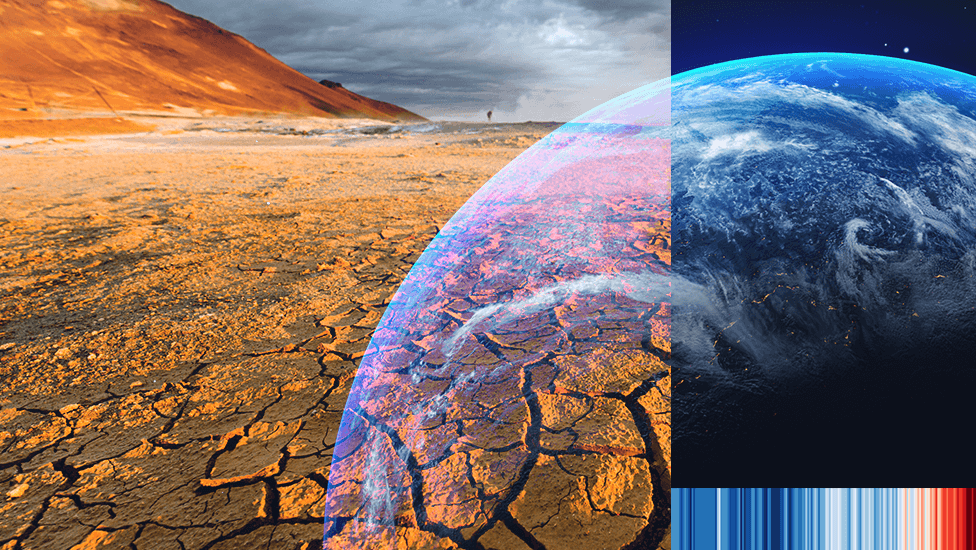

IN the background of rapid climate change impacts, many communities find themselves on the frontline of climate change, where they are hard hit and exposed.

This leaves the whole broad network of vulnerable communities seeking answers to their unenviable situations which have made survival such a difficult process. As such, their climate concerns have become their utmost needs, wants and necessities which can only be unpacked through deeper and structural communication pathways which situate the beneficiaries at the centre of adaptation strategies.

What communities on the frontline and marginal areas lack is the ability to confront the negative impacts of climate change which are essential tools, techniques, knowledge and information to foreground the vital engagement processes that transform livelihoods.

Therefore, for the correct interventions to materialise and bring results, development practitioners, government departments, climate change knowledge brokers and experts need to make communities their first port of call, inquire about their needs, opinions and engage them in good faith.

The communities’ needs and opinions can then be used to build a concrete climate case, story or agenda, aimed at mapping out their capacity to deal with climate impacts or lack of. This also includes capacity of those who bring in assistance earmarked to cushion them from climate shocks.

In this strategic engagement climate discourse, individuals and communities are the most important stakeholders who should never be by-passed. Their community-owned and driven knowledge system makes them essential community knowledge brokers and carriers of knowledge and information that can be used to get things done. In their own traditional and ecological viewpoints, they are vital communities knowledge banks, repositories and natural libraries or information sources.

Community climate needs assessment is part of information gathering from the grassroots to have broad insights into their livelihood options, challenges and solutions. These particular communities, reeling under the impacts of climate change, have their proven, tried and tested culture of doing things which is best described as community house styles. The house styles may constitute their century-old ways of adapting to climate change impacts including communicating their vital underlying needs and world views. This helps them to see and attach value to their traditional ecological reciprocal relations with the environment.

It is also significant in this regard to apprise the particular communities on why they are being engaged in the first place, why their knowledge is being sought and not the other way round. These communities also need to know the overall objective of the climate needs assessment and engagements, if the whole purpose is in line with their expectations and experiences.

- COP26 a washout? Don’t lose hope – here’s why

- Out & about: Bright sheds light on Vic Falls Carnival

- COP26 a washout? Don’t lose hope – here’s why

- Out & about: Bright sheds light on Vic Falls Carnival

Keep Reading

If there are questions to be asked and answers needed, then the communities will have to choose a spokesperson to communicate on their behalf, not an imposed person who is detached from their way of doing things. What this person says will be representative of the views of the communities.

The development drivers, government departments and climate experts use aggregated data to include marginalised women, children and disadvantaged community members so that they are included in the cross-cutting climate needs assessment divide. In this divide, their voices are amplified through user-friendly communication tools that are interactive and engaging. Their songs, dances, practices and socio-cultural issues are fused with communication because communication is central and it is used to level matters, making things clear and creating meaning.

Combined, traditional ecological and communication skills are informed ways used to challenge negative power, making voices of the marginalised heard and influence policy. Above all, communication is used for mobilising, awareness raising and generating knowledge as well as building partnerships.

The community members can also be broken down into focus groups, constituting groups of people sharing common climate situations, concerns and experiences. Before climate experts can suggest possible climate solutions, communities must be given the chance to come up with possible solutions to climate issues affecting them.

Through communicating climate needs, rural innovations for the marginalised and vulnerable can be pro-poor (for the poor), para-poor (working with the poor) and per-poor (innovation by the poor in their communities, and resilience is nurtured and built.

Responsible knowledge brokers use the bottom-up approach and horizontal digital networks to enable the local people improve their understanding of sustainable development issues and new knowledge economy. These are areas of interventions which can support per-poor empowerment by enabling the voiceless and the marginalised groups to communicate, share critical and strategic information as well as mobilise others.

In this regard, the local people share their experiences to achieve sustainable development goals.

It is essential that communities share their knowledge, speak out and build — not only resilience — but confidence too.

- Peter Makwanya is a climate change communicator. He writes in his personal capacity and can be contacted on: [email protected].