The Unity Accord signed between Zanu PF and Zapu on December 22, 1987 helped to end physical violence in places where the 5th Brigade operated.

For the first time since the deployment of the 5th Brigade in Matabeleland, 1983, and their Gukurahundi activities, the people of Matabeleland and some parts of the Midlands started to enjoy negative peace in the form of absence of physical or direct violence like killing, stabbing or raping for example.

Normal day-to-day activities and operations returned in areas where the 5th Brigade operated as curfews, countless roadblocks and physical harassment of people ended.

Stores, grinding mills, clinics and schools re-opened.

To date, the Unity Accord is celebrated as a historic achievement in the history of Zimbabwe, with December 22 set aside as a holiday, celebrated as “Unity Day” every year.

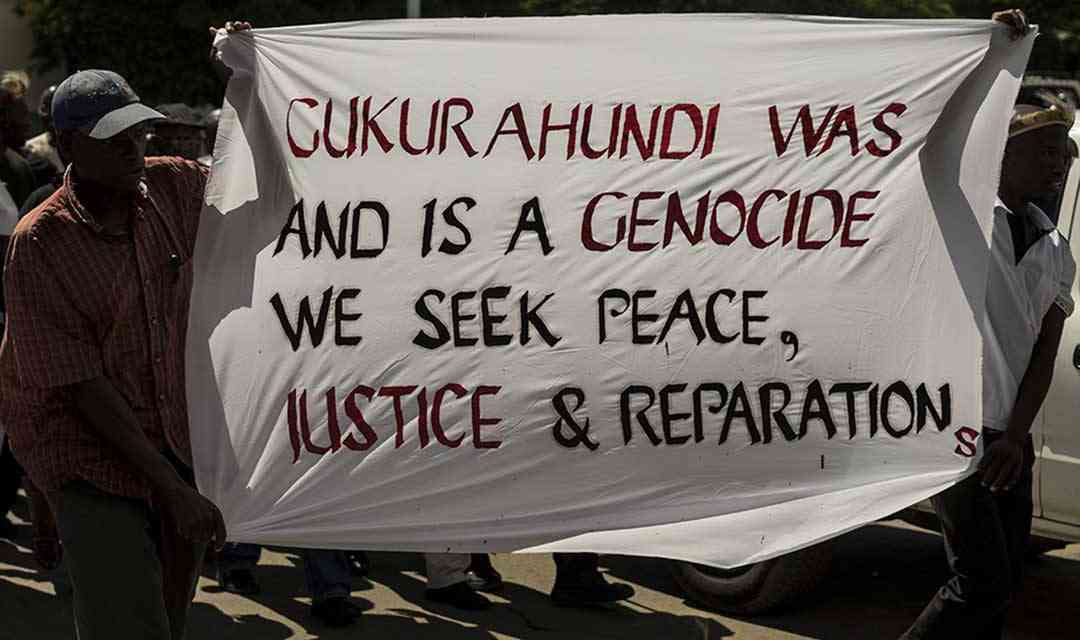

However, beneath the veneer of “national unity” brought by the Unity Accord, the emotional and physical scars were left unaddressed and are still festering to date.

First and foremost, it has to be noted that the negotiations leading up to the signing of the Accord were led and influenced by Zanu PF, the main perpetrator of Gukurahundi.

As alluded to in 2009 by Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni, the Unity Accord was nothing more than “a surrender pact” where Zapu was swallowed by Zanu PF.

- MPs are ignorant: Charamba

- Firm Faith postpones album unveiling

- ZimNinja holds first ever Ninjutsu Grading

- Corruption Watch: Get scared, 2023 is coming

Keep Reading

Put bluntly, the Unity Accord was a publicity stunt managed from the top by national elites.

Of course, the negotiations were in the hands of the local top political actors, which meant that the whole peacebuilding process was top-down, exclusionary, prescriptive and well managed by national elites to accommodate each other in an elite power-sharing arrangement.

Zanu PF as the perpetrator of the Gukurahundi conflict could not subject itself to a justice system where it would be made accountable to Gukurahundi crimes, with its officials possibly prosecuted.

The Unity Accord is a clear example of a peacebuilding process that was owned and led by elites who are complicit in human rights violations.

It is not possible to expect perpetrators to be impartial referees in a process where they are conflicted.

As Kenneth Omeje explains, there is little to expect from a peacebuilding process that are driven by compromised political elites.

The negotiations that gave birth to the Unity Accord of 1987 took place over a period of three years, from 1985-87, which is a very long period for any normal negotiations.

However, it is interesting to note that most of this time was spent by protagonists arguing over positions and the name of the envisaged “united party”.

Paradoxically, Zapu, which was a victim of the Gukurahundi conflict was asked under clause (8) of the unity agreement to take vigorous steps to eliminate and end insecurity and violence that was prevalent in Matabeleland.

Deliberately, as this clause suggests, the victim was forced to take the place of the perpetrator. This indicated an unwillingness by perpetrators

Besides ending the scourge of physical violence, the Unity Accord fell far short of addressing the causes and consequences of the Gukurahundi conflict.

There was no truth-seeking, truth-telling, trauma healing, remorse, forgiveness, compensation, accountability and reconciliation embedded in the Unity Accord negotiations and final document.

All the negative experiences of the victims of Gukurahundi were swept under the carpet and “forgotten”..

In fact, Zanu PF refused to acknowledge its active role in the Gukurahundi conflict. Instead, it shifted the responsibility to Zapu as seen through clause (8) of the agreement.

Referring to the brutal Gukurahundi atrocities in the post-2000 period, the former president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, said that it was, “a moment of madness”.

One wonders what that meant since he never elaborated what this actually meant.

The phrase could have been a subtle acknowledgement of his role and that of his party in the Gukurahundi conflict.

Besides that, it was just an empty and ambiguous phrase that did not help in anyway in addressing the consequences of the Gukurahundi conflict.

Overall, the process of the negotiations itself was not inclusive, neither was participatory and broad-based. It was an elite pact.

The end result was that political elites succeeded in accommodating each other as Joshua Nkomo, the leader of Zapu, was made second vice-president of Zimbabwe while a few of his colleagues in ZAPU were given some cabinet posts.

It was only after the signing of the Unity Accord that Joshua Nkomo went around Matabeleland, telling mesmerised and fearful victims of Gukurahundi that Zapu and Zanu PF had united in a “new party” called Zanu PF.

Immediately after taking overpower as the president through a “military assisted transition” in 2017, exactly thirty years after the Unity Accord,

Mnangagwa promised sweeping changes that would have, among other things, seen Zimbabwe address past human rights violation issues.

The Zanu PF election manifesto for the 2018 elections categorically spoke about capacitating the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC) to enable it to effectively discharge its constitutional mandate of addressing human rights violations of the pre- and post-independence periods.

Many victims of Gukurahundi breathed a sigh of relief, hoping that they were going to get justicel.

Through an Act of parliament, Mnangagwa operationalised the NPRC which had been in limbo for five years, half the period into its envisaged tenure of ten years.

However, to date, nothing substantive has taken place on the ground with regards to putting closure to the Gukurahundi issue.

From 2018 up until its termination in 2023, the NPRC did nothing significant in executing its mandate, confirming that Mnangagwa’s promise on dealing with the Gukurahundi issue was merely a publicity strategy and human relations project to gain acceptance after the coup..

In fact, considering that Mnangagwa was State Security minister (1980-88) under the Mugabe regime and directly linked to the violence, his dithering about Gukurahundi is not surprising.

Any genuine truth-telling process would implicate him in the human rights violations.

So, there are likely fears among Mnangagwa and his close associates that any acknowledgement of being involved in Gukurahundi atrocities would amplify calls for compensation from the victims of Gukurahundi.

This is something they are not prepared to shoulder given the long history of unaccountability and impunity in Zimbabwe.

The greatest challenge in seeking redress for Gukurahundi victims are the asymmetrical power relations inherently embedded in the processes that seek to resolve the issue.

It is difficult to expect traumatised victims to demand from an entrenched political elite that still control the levers of power admit guilt and atone.

No one acknowledges guilt for Gukurahundi atrocities and there is no mention of perpetrators.

This is the tragedy of a political elite leading a transitional justice process where it is the guilty part.. Its perception of resolving the challenge will always be far from what really needs to be done.

The recent initiative to resolve the Gukurahundi issue conceptualised by the Mnangagwa administration, known as the Gukurahundi community outreach programme, which uses only traditional leaders as a platform to facilitate hearings on the Gukurahundi atrocities has been roundly criticised by many stakeholders (such as pressure groups like Ibhetshu likazulu, political parties; ex-Zipra combatants, churches, academics and civil society organisations) who were left out of the process.

The major accusation of the process is that it is poorly designed, partisan, exclusionary, inadequate and meant to achieve predetermined outcomes.

In Zimbabwe, traditional leaders are generally viewed as appendages of Zanu PF because they have been politicised and “bought” through cash allowances, expensive cars, bore holes, farms, tractors and other material rewards so that they help Zanu PF to remain in power.

Traditional leaders are viewed as politically connected to Zanu-PF and not as impartial arbiters.

Using only them and leaving out other relevant stakeholders discredits the whole process.

Like the Unity Accord, the Mnangagwa initiative lacks grassroot support and its outcomes are likely to be disputed and resented by the people of Matabeleland, who view the whole exercise as a stage-managed project that is engineered from above rather than a genuinely bottom-up peacebuilding process.

Mnangagwa’s aim seems to be more inclined towards pacifying the people of Matabeleland rather than redress based on acknowledgement of wrongdoing, forgiveness, atonement, compensation, and reconciliation.

*Sifiso Ndlovu is based at the University of Mpumalanga in South Africa