I have had close encounters with two devastating modern genocides in Africa; one through lived experience, and the other through witnessing how a better nation can build after unthinkable loss.

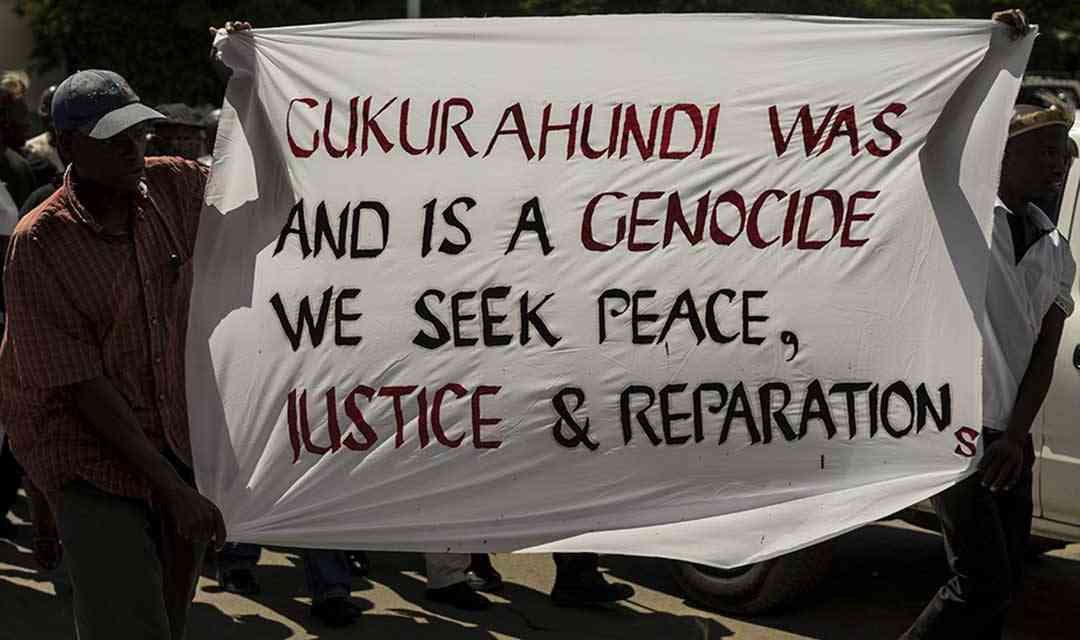

Gukurahundi, whose proximity to me as a Zimbabwean from Matabeleland is deeply personal, has shaped much of my understanding of who we are and what we have failed to confront as a country.

Born and raised in Nkayi, infamously known as KoMnyamubambile for its entrenched underdevelopment, under-resourced schools, poor health services and meagre economic opportunities, I grew up knowing that our struggles were never simply about poverty.

They were about a history that hovered over every conversation, every silence, and every road like the notorious Nkayi road itself.

For people from my region, Gukurahundi has never been a chapter in a history book; it has been a constant presence.

My other encounter with genocide came during a week-long academic assignment in Rwanda two years ago.

Standing inside the Kigali Genocide Memorial, surrounded by the names, faces and bones of some of the more than 800 000 victims of the genocide against the Tutsi, I could not escape a sobering contrast.

Rwanda, scarred far more severely and at a scale that defies comprehension, has built more than 250 memorial sites dedicated to memory, healing and national reckoning.

- Ziyambi’s Gukurahundi remarks revealing

- Giles Mutsekwa was a tough campaigner

- MPs are ignorant: Charamba

- New law answers exhumations and reburials question in Zim

Keep Reading

In Zimbabwe, by contrast, our few Gukurahundi memorial plaques, erected not by the state but by the pressure group Ibhetshu Likazulu, have been bombed into smithereens.

While some Rwandans I met spoke of a cathartic peace emerging from truth-telling and remembrance, the persecution of artists like Owen Maseko and activists who have pushed for Gukurahundi justice tells a different story at home.

Zimbabwe’s journey beyond Gukurahundi and the 1987 Unity Accord, signed seven years before the Rwandan genocide, remains unfinished.

This is why the chiefs-led community consultations currently unfolding in Matabeleland North and South provinces feel historic, regardless of their yet to be known outcomes.

They have reopened old wounds but also revived long-suppressed hopes that Zimbabwe may finally be ready to confront its past honestly.

For many of us in Matabeleland and parts of the Midlands, this moment forces us to reckon not only with national memory, but with our personal stories, those faint childhood recollections that later reveal themselves as trauma.

As I reflect on my own experiences, I realise I am not merely an observer of Gukurahundi; I am one of its victims, part of a generation whose pain has long been excluded from official narratives and whose healing has been deferred for decades.

One of the most difficult issues confronting people in Matabeleland today is the question of victimhood, that is who counts, who is acknowledged, and who is left outside the frame.

This debate has sharpened since the launch of the chiefs-led process.

For those of us supposedly “born free,” the stories we encountered later in life made our own memories snap into focus. When I first read Christopher Mlalazi’s Running with Mother, I couldn’t help but substitute Rudo, her mother, aunt, and cousin with myself, my own mother, aunties, and cousins fleeing through the thick Gwampa forest to catch a bus to Bulawayo.

I remembered the gunshots, which I have since confirmed to have come from around Cross Zenka, where an entire family perished.

I recalled another morning when my older cousin, lying on her back singing to herself, quickly pulled a blanket over her head as two soldiers appeared at the window of our mud hut.

They forced the door open and ordered her out. She followed them, only to come later, visibly distressed.

Only years later did I understand what that moment might have meant.

Rape was part of the modus operandi of the Fifth Brigade.

I also remember the many fatherless children, just a few years younger than me, who appeared in every homestead.

Together with their own children, they remain undocumented and stateless.

But the memory that haunts me most is of my grandmother. May her gentle soul rest in peace.

She endured vicious slaps that left her partially deaf and with permanently swollen feet after soldiers stomped on her with those monstrous military boots.

Her “sin”, like Lovemore Majaivana, was failing to understand their language.

She could easily have died that day; one soldier cocked his gun, ready to shoot, and was only restrained by his colleague.

Even now, I feel the sting of secondary trauma when I recall how, as a child, I narrated the incident with a strange, nervous excitement to horrified neighbours.

In any genuine social-justice process, one willing to turn over every stone and liberate both perpetrators and victims, I must submit that I am a Gukurahundi victim, just like the many others in Bulawayo, the Midlands, and the diaspora whom the current chiefs’ process does not fully account for.

In the long and painful Gukurahundi timeline, which, sadly, extends far beyond the signing of the 1987 Unity Accord, the chiefs’ process will be historic regardless of recommendations and impact.

I remember how the signing of the Accord sent Ndux Malax, Black Umfolosi and other artists in Matabeleland into a melodious frenzy – “Unity Number 1”!

Only later, through Mthulisi Mathuthu’s chapter in a recent volume co-edited by Mandlenkosi Mpofu, Kirk Helliker, and myself, did I learn that no single musician from the rest of the country produced a song about the Unity Accord.

Almost 40 years later, its meaning still feels hollow to those of us who did not “qualify” as victims at the time, the born-frees who lacked the context to understand its significance.

Younger generations may fear the Nkayi and Lupane roads more than Gukurahundi itself and mock Father Zimbabwe for signing the Accord, but survivors like my grandmother regarded it as a major reprieve from almost certain death.

Still, the chiefs’ process has stirred deep feelings across Matabeleland.

Once beaten, twice shy. The resounding call has been “Nothing for us without us.”

Civil society demanded to participate openly, no longer from the shadows, and the local media rightly sought to bear witness for the nation and the world.

Zimbabwe needs a Gukurahundi truth and reconciliation framework that brings together national and international expertise and ensures adequate protection for participants.

Only then can we genuinely say “Never Again” in one voice as a country.

However, despite widespread and understandable scepticism, and thanks in part to voices like Sipho Malunga, I am now persuaded to view the process as a glass half-full rather than empty.

The reported 26 000 victims who have already testified before chiefs in the two Matabeleland provinces, surpassing the roughly 22 000 who appeared before the South African TRC over three years, reveal not only the scale of Gukurahundi’s devastation but also how much fear, trauma, and memory have remained buried for decades.

If these numbers can be trusted, they signal the depth of suppressed pain and the sheer volume of stories people have long wanted to tell.

They also suggest that this process, if handled responsibly, will generate invaluable data for civil society, policymakers, and scholars.

It is remarkable that only 35 years after the atrocities, Mandlenkosi Mpofu and Percy Makombe’s Memory and Erasure became the first book-length collection on Gukurahundi, not because of academic or civic neglect, but because the subject itself was taboo.

One can only hope that the chiefs remain united in purpose and preserve the moral authority rooted in the sacredness of traditional leadership, resisting political pressure and patronage. Ultimately, although a clear pathway to full justice for all victims remains uncertain, we must hold onto the hope of a Zimbabwe where Gukurahundi no longer determines identity, belonging, or opportunity, where every Zimbabwean seeks a sincere break from that dark and traumatic past.

In light of the December 22commemorations, may this moment prompt genuine soul-searching, a recommitment to building a nation that prioritizes justice for the victims, both living and departed.

For there can be no Zimbabwe for all until Gukurahundi is truthfully confronted, resolved and memorialized.

*Dion Nkomo is a professor based at Rhodes University. He writes in his personal capacity.