Xenophobia often described as the irrational fear or hatred of outsiders has become an emotionally charged and politically manipulated phenomenon across many parts of the world, including Africa.

In countries like South Africa, periodic waves of xenophobic violence have left scars, not only on the bodies of migrants, but also on the collective conscience of the continent.

This piece seeks to interrogate the multifaceted nature of xenophobia while providing an artistic analysis that situates the artist as a witness, a prophet, and a cultural warrior navigating the fragile terrain between nationalism and humanity.

Xenophobia is often fueled by socio-economic frustrations, political scapegoating, and historical amnesia.

Migrants are conveniently turned into "others", or invaders who take jobs, burden social services, or dilute national identity.

These narratives, deeply entrenched in political rhetoric and public discourse, serve as justification for the systemic exclusion, and at times, violent expulsion of foreign nationals, especially from other African countries.

The irony of it all lies in the shared colonial histories, intertwined liberation struggles, and pan-African dreams that are often forgotten or conveniently ignored.

But beyond policy papers and academic debates, xenophobia is a deeply emotional issue as it is about fear, insecurity, power, and trauma.

- Zim headed for a political dead heat in 2023

- Record breaker Mpofu revisits difficult upbringing

- Tendo Electronics eyes Africa after TelOne deal

- Record breaker Mpofu revisits difficult upbringing

Keep Reading

It is here that art becomes an essential tool not just for documentation, but for interpretation, resistance, and healing.

In the visual arts, xenophobia has been challenged through installations that simulate displacement, photography that captures the rawness of suffering, and murals that proclaim unity amidst division.

South African artist Haroon Gunn-Salie’s Soft Vengeance series uses empty clothing forms to represent lives lost and displaced.

Similarly, Zimbabwean photographer Kudzanai Chiurai’s work captures the aesthetics of protest, blending afro-futurism and revolutionary symbolism to critique societal fractures including xenophobia and post-colonial betrayal.

Poetry, too, offers an emotive language for understanding the complexity of xenophobic violence.

Consider the words of Nigerian poet Niyi Osundare: "No border can hold the dream of a refugee." In one line, the poet reminds us of the futility of artificial boundaries when it comes to human aspiration and survival.

In music, xenophobia is often challenged through pan-African collaborations that defy linguistic, ethnic, and national barriers. Afro-jazz and hip-hop musicians from Zimbabwe, Nigeria, and South Africa have used their platforms to denounce hate and advocate for solidarity.

Oliver Mtukudzi’s collaboration with South African artists was not just musical it was a political statement of unity in diversity.

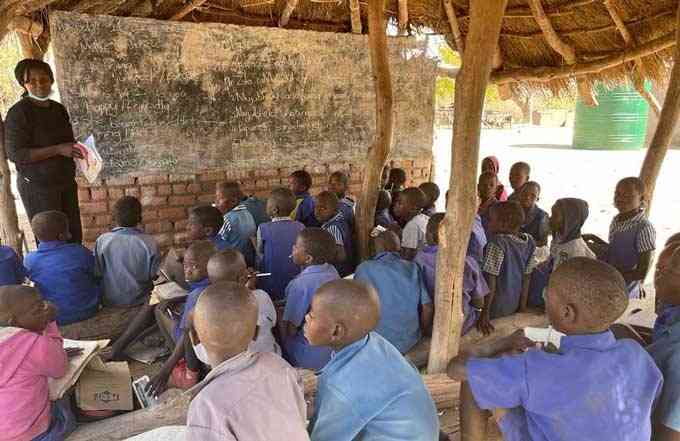

Theatre, with its immediacy and intimacy, has also been a powerful medium in interrogating xenophobia. Community-based theatre projects, like those initiated by the Market Theatre Lab in Johannesburg, have provided platforms for locals and migrants to share stories, break stereotypes, and foster empathy. These participatory performances offer more than entertainment—they are a kind of civic rehearsal for reconciliation and mutual understanding.

Through dance, the body itself becomes a site of resistance. Choreographers such as Gregory Maqoma have used contemporary African dance to depict both the tension and possibility of co-existence, questioning how borders and identities are inscribed on skin, in muscle, and in movement.

Ubuntu, a southern African philosophy that affirms umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu, which means that a person is a person through other people has often been invoked in discourses of reconciliation, nation-building, and moral regeneration.

However, its potential as an aesthetic and cultural imperative remains underexplored in mainstream academic and policy circles.

In the face of rising xenophobia, particularly across the Global South where historical solidarities have been replaced by new forms of nationalistic exclusion,

Ubuntu emerges not just as a moral code, but as a radical artistic praxis one that calls upon creatives to reimagine and reconstruct collective belonging.

Xenophobia thrives on the construction of the other - an imagined stranger who is not entitled to the same moral consideration, rights, or resources as the in-group.

It is not merely a sociopolitical crisis, but a failure of imagination, empathy, and historical memory.

In contrast, Ubuntu centers interdependence, mutual recognition, and relational identity.

It dissolves the binary of citizen/foreigner by asserting that one's humanity is incomplete without others.

This is where art becomes central. Artistic expression informed by Ubuntu does not seek to represent the Other as an object of pity or charity, but as a co-constitutor of reality and meaning.

Through Ubuntu, the creative process becomes a site of resistance against dehumanization and a platform for restoring social harmony.

In societies wounded by the scars of colonialism, apartheid, and post-colonial inequalities, the artist occupies a unique role a custodian of memory and a visionary of futures.

When an artist paints a portrait of a refugee child, they are doing more than capturing a face; they are inviting the viewer to engage with narratives of displacement, trauma, and resilience.

A song about migration becomes not only a lament but a form of oral historiography, connecting disparate geographies through affect and memory.

Moreover, the performative arts especially theatre and poetry can hold space for collective introspection. Plays that challenge nationalism or satirical poetry that exposes state complicity in xenophobic violence are not simply cultural artifacts.

They are acts of defiance, healing, and social pedagogy. The artist, therefore, functions as both griot and grioterre storyteller and social gardener tilling the soil for new, inclusive imaginaries.

While politics often thrives on the logic of boundaries of who belongs and who does not belong, art is guided by Ubuntu and subverts this logic.

Art insists on transcending constructed borders (both physical and epistemic) by invoking shared vulnerabilities and hopes.

It builds bridges across difference and creates liminal spaces where dialogue, empathy, and identification can occur.

These aesthetic encounters humanize the “stranger,” revealing the absurdity of xenophobic logics that reduce individuals to their nationality or ethnicity.

This is particularly significant in African contexts where post-independence borders were colonial impositions, not reflections of indigenous identities or social cohesion.

Thus, when contemporary African states deploy xenophobic violence against fellow Africans, it reveals a deeper crisis and a colonial wound left unhealed.

Ubuntu art intervenes here, not by offering simplistic answers, but by restoring fractured memory, reminding us of a time when solidarity trumped sovereignty.

An Ubuntu-informed artistic philosophy compels creators to move beyond commodification and individualism. It emphasizes responsible representation, community-oriented themes, and participatory processes.

The arts becomes not just entertainment but a form of ethical labor. In this way, Ubuntu echoes the idea of “art for life’s sake” where artistic expression is intertwined with societal healing and moral responsibility.

Ubuntu aesthetics do not shy away from complexity. Instead, they invite multiplicity and heterogeneity while still affirming a common humanity.

Such an approach is especially necessary in multicultural urban centers like Johannesburg, Harare, or Lagos—where diverse migrant communities co-exist in precarious harmony, often scapegoated for systemic failures they did not create.

Art becomes a tool to reconfigure what it means to be a citizen not merely a legal status, but a lived, felt, and cultural affiliation.

Ubuntu art does not erase difference, but it undermines hierarchies that privilege one identity over another. Through visual art, music, performance, and storytelling, it is possible to construct counter-hegemonic narratives that include migrants, refugees, and “foreigners” as part of the communal self.

Such interventions also call into question the exclusivist tendencies of post-colonial nationalism. While many liberation movements in Africa were built on pan-African ideals, modern states have often retreated into nativism and ethno-nationalism. Ubuntu art rekindles that lost vision of interconnected liberation - one where no African is a foreigner on African soil.

Xenophobia is not just a political or economic issue; it is a spiritual and existential rupture and a disavowal of our shared fragility and dignity.

Where politics builds walls, art—rooted in Ubuntu builds bridges. Not all art can dismantle systems of oppression, but it can gesture toward possibilities, provoke difficult conversations, and restore the sacredness of human connection.

Let the artists paint, sculpt, choreograph, sing, write, and perform us into new worlds where empathy overrides fear, and difference is not a threat but a gift. Let art become a sanctuary of belonging, and let Ubuntu become the soul of our creative consciousness.

In the words of Archbishop Desmond Tutu (pictured): “My humanity is caught up, is inextricably bound up, in yours.” To be human is to always belong.

- Raymond Millagre Langa is a Zimbabwean musician, poet, and cultural activist dedicated to using the arts as a platform for social change and heritage preservation. He is the founder of Indebo Edutainment, an initiative that blends education and creative expression to empower communities.