Despite all the hullaballo in Parliament over the banning of second-hand clothes, the fact of the matter is that this trade has not been banned because there is no law to enforce the ban.

BY TARISAI MANDIZHA

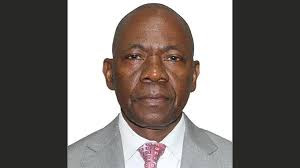

In August, Finance minister Patrick Chinamasa announced the ban of second-hand clothes effective September 1 to protect the local industry.

Chinamasa said despite the high customs duty of $5/kg on clothing and 40% plus $1 duty per pair of shoes, the products had continued to flood the market.

“I, therefore, propose to remove second-hand clothing and shoes from open General Import Licence. Furthermore, any future importation of second-hand clothing and shoes will be liable to forfeiture and destruction,” said Chinamasa.

A visit to flea markets in Harare last week established that second-hand clothes are still the most trading commodity at Mupedzanhamo, Copacabana and Charge Office markets.

Zimbabwe Informal Sector Organisation (Ziso) director Promise Mkwananzi said government should first formalise the ban of second-hand clothes by promulgating relevant laws before trying to seize the goods. He said government must also realise that due to economic challenges, people had no option but to engage in these types of ventures.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

“The ban on second-hand clothes must be formalised into law first and foremost. But most importantly, government must realise that due to the crumbling economy, people have no option but to resort to this kind of venture,” Mkwananzi said.

Vendors said the move by government to ban second-hand clothes would worsen their situation and promote smuggling and corruption in the country.

Second-hand clothes vendor Bee Mushambi said he had resorted to the trade as there were no jobs on the market. He said instead of banning second-hand clothes, government should put customs duty which should be friendly to both the government and vendors.

“Vendors are prepared to pay for goods because imposing a ban, like what they have done at the moment, will increase smuggling and only a few would benefit. It’s better to formalise the sector and government will earn something out of it,” he said.

“I think they [government] want money but at the end of the day, they should formalise the sector by introducing a system that helps both government and the vendors work together. It’s actually better if it can be formalised because already, it costs so much to get these clothes here.”

A vendor at Mupedzanhamo market who refused to be named, said while it was illegal to bring in second-hand clothes in the country, people had no option because of the prevailing economic difficulties in the country.

“It’s better if government can charge us rather than to stop us from selling second-hand clothes. What they are doing is encouraging corruption and government will lose a lot,” he said.

“If they say they are banning second-hand clothes, they are breeding more corruption in the country,” the vendor said.

Another vendor Tapona Munde said government should not panic as other economies sold second-hand clothes.

“Now that the economy is largely being driven by the informal sector and as part of indigenisation, government should actually promote these enterprises. why can’t they put in place taxes which are friendly?

“The bulk of the stuff is being smuggled and what they recover is only a third. If government puts in place a tax to import these goods at an affordable rate, this will bring a lot of transparency.”

He said most second-hand clothes came from Zambia, Mozambique, Malawi, Botswana and South Africa.

Mkwananzi said there was a big market for second-hand clothes in Zimbabwe as the sector serviced the majority of the people who could not afford new clothes.