What has happened to our literature? asks Tinashe Mushakavanhu in the Bookworm column (The Standard January 26 to February 1 2014).

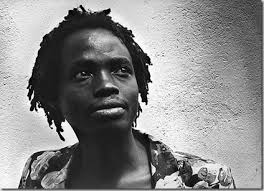

Murray Mccartney

The first of his many answers is to suggest that local publishers have killed it. As a local publisher myself, I cannot take accusations of murder lightly, and ask that you allow me space to reply.

However, given the impassioned and scattershot nature of Bookworm’s polemic, it really is difficult to know where to start. Let’s take his points as he offers them.

“I wonder if we are still the nation that produced [Musayemura] Zimunya, [Solomon] Mutsvairo, [Dambudzo] Marechera, [Yvonne] Vera, etc?” To this pantheon, I would add Charles Mungoshi, and I would tentatively assert that, no, we are not still that nation. I knew Vera and Marechera well, and I know them to have been better-read than just about anyone I’ve ever met. I know Mungoshi, and would say the same of him. A cursory review of the contemporary literary scene — and of the unsolicited manuscripts we receive — suggests that such a thirst for literature (and a slaking of that thirst) is less common among writers now than it was in the past. But that is a debate for another day.

Because publishers are in thrall to the school syllabus, Bookworm suggests, “our writers have to produce … literature that does not offend … that is politically correct.” First of all, even if we accept the premise — and the evidence of our own list roundly contradicts it — his assertion can only be true if there is no other avenue to publication than using a publisher. But that is not the case. If anyone cares to write an offensive, politically incorrect novel, they are free to self-publish it.

“Sadly, there is now a culture in Zimbabwe to anthologise its authors …”. This reference to the published short story predominating over the published novel is not a reflection of “a culture” of publishing; rather it is a reflection of the form many writers prefer to adopt. “… what we know of them is fragmentary, what we see of their potential genius are just but glimpses”. Elegantly put, but you know well enough the rarity of “genius”; and good short story writers aren’t always good novelists. And an excellent Zimbabwean novel will rarely want for a publisher.

As for publishers having “usurped the role and functionality that literary magazines are expected to play”, we must again plead not guilty; and to the proposition that our publication of short stories is “stifling the local literary scene”, we would argue “the more the better.” Let magazines be launched, and let a thousand flowers bloom.

- In Full: Fourteenth post cabinet briefing: May 31, 2022

- Rwanda calls out Zim on genocide

- Govt sweats over Rwandan fugitive links

- Govt plans to woo diaspora investors

Keep Reading

Bookworm moves on to a consideration of race in the canon of Zimbabwean writing, but crisscrosses between fiction and non-fiction in a way that muddies his thesis. On the one hand he notes that, in the context of fiction, “White writers are absent or minimally discussed in the critical works”. But who are these absentees? John Eppel? Bryony Rheam? Alexandra Fuller? So few that one wouldn’t expect them to be much more than “minimally discussed”.

On the other hand he is struck by the fact that “most of the influential books about Zimbabwe are written by white Zimbabweans or European visitors”. I don’t know how he would define “influential”, but if fiction is to be included he should be careful about brushing aside Petina Gappah, NoViolet Bulawayo, Brian Chikwava and Tendai Huchu.

I would be happy to join Bookworm in his disquiet at the acclaim heaped on some books about Zimbabwe that have caught “the empathy of the global media,” but these tend to be produced in Europe and America, and you can’t blame the local publishing industry for that. Murray Mccartney is a Director at Weaver Press, Harare