In the last few years my research as a scholar of Zimbabwean literature has shifted towards the archive — its creation, or absences. I am interested in what remains, after people, especially writers, are gone; fragments, photographs, scraps, ephemera and what these reveal of their character or thinking.

By Tinashe Mushakavanhu

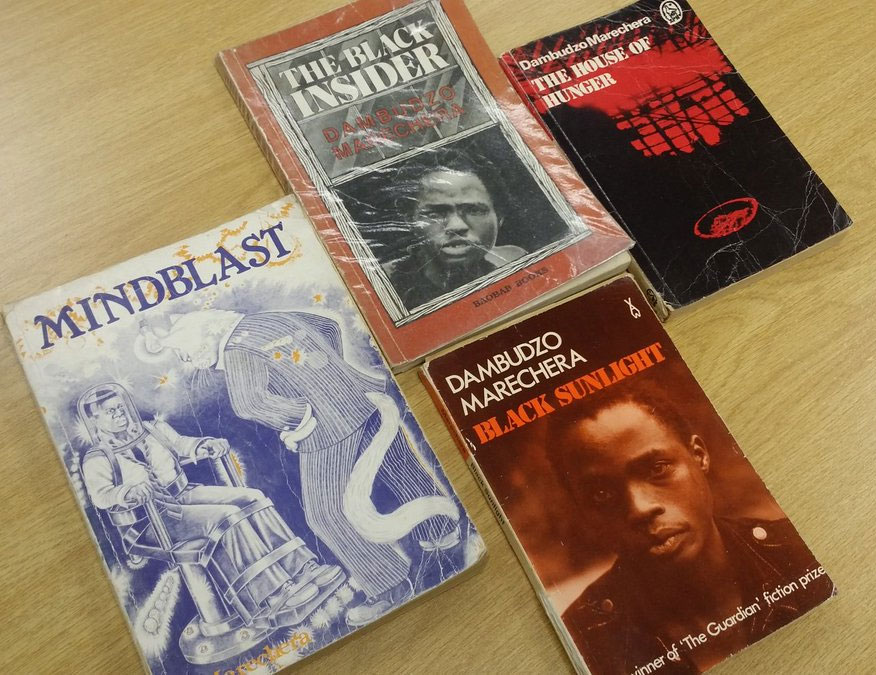

After Dambudzo Marechera died in August 1987, friends and family came together to establish a trust in his name. The primary goal was to rescue his scattered output. No other Zimbabwean writer has commanded so much power from the grave than Marechera. His unpublished writings are archived in Berlin, Harare and the city of Reading. Some of these writings have since been posthumously published to wide critical acclaim. In his lifetime Marechera only published three books — The House of Hunger (1980), Black Sunlight (1980) and Mindblast (1984).

For a man who was known for the peripatetic nature of his lifestyle, Marechera is an exception. He is the most comprehensively archived black Zimbabwean writer. Were it not for the preservation of his writings, his influence might have been little. So many writers of great talent and promise have died with their work. Philip Zhuwao died unnoticed and remains unknown. Reuben Pakaenda. Stanley Ruzvidzo Mupfudza. Chenjerai Hove. Freedom TV Nyamubaya. Alexander Kanengoni — the list is long. All these writers when they transitioned they had completed new unpublished work. What is happening to the material? Where is it? Do their families know what to do with it?

A few months ago, I received an old manuscript, that was being eaten by termites. Some of the pages were half gone.

Though there are Yvonne Vera archives in Canada, South Africa and the United States, her material is not easy to access. When she died in 2005, Vera had finished a novel, Obedience. There is a report that her mother and younger brother decided it should be deposited in the archives at Peterborough University where she taught briefly for the next 10 years.

The internet promises open access and the ubiquity of information, yet Zimbabwean writers are missing on the worldwide web. A simple google search does not yield much. Wikipedia does not have entries of many Zimbabwean writers, their biographies or accomplishments. Even their photos.

This raises fundamental and complex questions about what happens to the works of our writers after they die, or before, when they’re still here, and are writing. This isn’t just a highbrow lament.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

One of the most distressing effects is lack of small black publications that provide both a springboard and an outlet for aspiring and established writers. This has had a corollary effect too: the decrease in the number of published novels by black authors. It is not that these novels are not there — they are locked in trunks, pressed under beds, or saved on hard drives. This archive remains hidden, out of view, and in the Zimbabwean case, so many times.

Perhaps, it is time our families learnt how to preserve creative work by their kith and kin who write. They are valuable, those scraps of paper, the letters, the notebooks. The literary estate of an author who has died does not just consist of the copyright and other intellectual property rights of their published works, but also includes, for example, original manuscripts of published work, which potentially have a market value, unpublished work in a finished state or partially completed work and papers of intrinsic literary interest such as correspondence or personal diaries and records.

If you have those manuscripts left behind, let’s talk, let’s build the archive together. For feedback, email: [email protected]