in the groove with Fred Zindi

Between 1985 and 1995, everywhere you went within Zimbabwe, you would come across young people, especially boys, wearing dreadlocks.

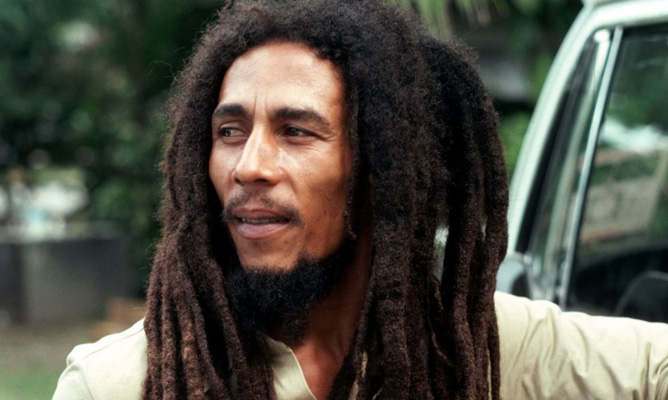

Dreadlocks had become the fashion hairstyle of that period. The reasons behind wearing such hairstyles were two-fold: Either one wore them as a fashion trending during that period or they followed the Rastafarian beliefs prevalent in Zimbabwe at that time. After all, the great reggae icon, dreadlocked Bob Marley, who was a Rastafarian, had visited the country and influenced Zimbabwe’s youth culture.

As Marley once said in an interview with local radio personality Mike Mhundwa, “Locks are a way of life for the Rastafarian. Dreadlocks are my identity. They tell the world who I am. A Rasta believes everything should be natural, no spray deodorant, but smell like peppermint soap, no shaving, no cutting of any part of the body. Females should not wear long pants, jeans or slacks and no make-up. Rastas do not eat meat, only fish, and Rastas should treat their body as a temple.”

Mhundwa was taken aback by this philosophy and even started to grow dreadlocks. Up to now I do not know whether he was a Rasta or not. His dreadlocks seemed to be just a fashion of the time. When I invited him to my house for a braai, he could not resist having a go at the sausages that were being roasted on the braai stand.

According to the literature I have come across, Rastafari movement locks are symbolic of the religious beliefs based on the Lion of Judah. The Lion of Judah is sometimes centred on the Ethiopian flag which has significant colours: red, gold and green. Rastafarians believe through their Bible readings that Haile Selassie is a direct descendant of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, through their son Menelik I. Their dreadlocks were inspired by the Nazarites in the Bible who wore dreadlocks.

Many musicians in Zimbabwe during the period 1985 to 1995, as reggae became more and more popular, decided to emulate Bob Marley by growing dreadlocks. But it was not only musicians. Many youths who had been inspired by Marley’s music and his beliefs decided to sport dreadlocks much to the chagrin of their parents. Dreadlocks were now being associated with mbanje (ganja/marijuana) smokers, which is one thing many Rastas, including Marley, believed in. Marley would often say: “Ganja smoking is good for you because it makes you wiser. Babylon don’t want you to smoke it because it makes you wiser than them.”

In 1995, one particular youth wearing dreadlocks applied for a passport to go to Botswana and was refused the passport because of his locks. He had to take the registrar-general to court. The court endorsed the registrar-general’s decision. Another dreadlocked youth who had completed a medical degree and wanted to work as a doctor failed to secure a job, despite the shortage of doctors in the country, because of his dreadlocks. It was only after he had shaved off his locks that he finally got a job. He was advised that it was not worth it being defiant as shaving off his locks would not take away his beliefs.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

When reggae music gained popularity and mainstream acceptance in Zimbabwe in the 1980s, thanks to Bob Marley’s music and cultural influence, the locks (often called “dreads”) became a notable fashion statement nationwide; they were worn by musicians, prominent authors, actors, athletes, Members of Parliament and rappers.

In Jamaica, this move started as a religious statement with the Rastas.

Rastafari, sometimes termed Rastafarianism, is a religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is more like a social movement. There is no central authority in control of the movement and much diversity exists among practitioners, who are known as Rastafari, Rastafarians, or Rastas.

Rastas refer to their beliefs, which are based on a specific interpretation of the Bible, as “Rastalogy”. Central is the belief in a single God — referred to as Jah who partially resides within each individual. Haile Sellasie, the Emperor of Ethiopia between 1930 and 1974, is given central importance. He is often referred to as King of Kings and Lord of Lords, the conquering Lion of Judah. Many Rastas regard him as an incarnation of Jah on Earth and the Second Coming of Jesus, another figure whom practitioners revere. Other Rastas regard Haile Selassie not as Jah incarnate, but as a human prophet who fully recognized the inner divinity in every individual. Rastafari is Afro-centric and focuses its attention on the African diaspora, which it believes is oppressed within Western society, or “Babylon”. Many Rastas call for the resettlement of the African diaspora in either Ethiopia or Africa more widely, referring to this continent as the Promised Land of “Zion”. Rastas refer to their practices as “livity”. Communal meetings are known as “groundations”, and are typified by music, chanting, discussions, and the smoking of ganja, the latter being regarded as a sacrament with beneficial properties. Rastas place emphasis on what they regard as living “naturally”, adhering to its dietary requirements, twisting their hair into dreadlocks, and following patriarchal gender roles.

Rastafari originated among impoverished and socially disenfranchised Jamaican communities in 1930s Jamaica. Its Afro-centric ideology was largely a reaction against Jamaica’s then-dominant British colonial culture. It was influenced by both Ethiopianism and the Back-to-Africa movement promoted by figures like Marcus Garvey. The movement developed after several Christian clergymen, most notably Leonard Howell, proclaimed that Haile Selassie’s crowning as emperor in 1930 fulfilled a Biblical prophecy. By the 1950s, Rastafari’s stance had brought the movement into conflict with wider Jamaican society, including violent clashes with law enforcement. In the 1960s and 1970s, it gained increased respectability within Jamaica and greater visibility abroad through the popularity of Rasta-inspired reggae musicians like Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Burning Spear and Bunny Wailer. Enthusiasm for Rastafari declined in the 1980s, following the deaths of Haile Selassie and Bob Marley, but the movement survived and has still got presence in many parts of the world, including Zimbabwe. In Epworth and Glen Norah, there are scenes where the movement is still very strong and Rastas gather for prayer meetings every weekend.

The Rasta movement is decentralised and organised on a largely cellular basis. There are several denominations, or “Mansions of Rastafari”, the most prominent of which are the Nyabhingi, Bobo Ashanti, and the Twelve Tribes of Israel, each offering a different interpretation of Rasta beliefs. There are an estimated one million Rastas across the world; the largest population is in Jamaica, although communities can be found in most of the world’s major population centres. The majority of practitioners are of black African descent, although a minority come from other racial groups.

Locks have been worn for various reasons in our culture: as an expression of deep religious or spiritual convictions, ethnic pride, as a political statement and in more modern times, as a representation of a free, alternative or natural spirit. Their use has also been raised in debates about cultural appropriation with the more conservative members of our society secretly and sometimes openly despising them.

A few years ago I walked into the newsroom of one of the nation’s daily newspapers. I saw around seven journalists sporting dreadlocks. I identified some of them as followers of reggae music but not necessarily Rastas. Many years later, after they realised that they were probably not getting promoted because their bosses did not like the idea of their staff wearing dreadlocks, some of them shaved them off and have since been promoted to higher or more senior posts.

From the year 2000 onwards, many youths have found it unnecessary to grow dreadlocks as their parents do not necessarily approve of them. More so, when looking for jobs, which are already scarce, they have become more conscious about their appearance and choose to look “presentable”. Only artistes such as film-makers, visual artistes and musicians who feel that they are already employed, have kept the tradition of dreadlocks going. Young and upcoming musicians such as Enzo Ishall, Killer T, Tocky Vibes, Seh Calaz, Ricky Fire and Soul Jah Love in the Zimdancehall movement still wear dreadlocks while their senior artistes such as Thomas Mapfumo, Jah Prayzah and Winky D see that as a way of expressing themselves as musicians and being different from ordinary people. None of them strictly adhere to Rasta beliefs. Sadza and beef stew is a prominent diet among most of them. Some are into spliff (ganja) while others are not. The common element is, of course, the music.

I know a few people that have locks simply because of Bob Marley, reggae music or fashion and they are neither Rasta nor artistes. There are others who have no idea why they wear them. To these people I ask the question: Does the wearing of dreadlocks signify anything?

Feedback: [email protected]