In the groove with Fred Zindi

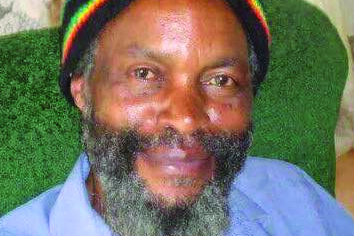

In six days’ time, on Saturday May 11, the Rastafarian community and many reggae fans all over the world will be commemorating the death of Bob Marley. However, the Zindi family and many of Zimbabwe’s reggae fans will be commemorating one year after the passing-on of former Transit Crew founding member and larger-than-life guitarist, Nicholas “Samaita” Zindi, with the main focus being on his legacy.

Samaita died on May 9 last year after succumbing to prostate cancer, two days short of his number one inspiration Bob Marley’s death date.

As Mark Twain said on his death bed, “Death is the only immortal who treats us all alike, whose peace and whose refuge are for all: the soiled and the pure, the rich and the poor, the loved and the unloved.”

Samaita is now mixing with everybody who left this planet before and after his own death. We hope and trust that wherever he is, he is united with his fellow musicians who died after him, the likes of Oliver Mtukudzi, Dorothy Masuku and Tedious Matsito.

His death was described by many of his followers as a big loss for Zimbabwe. The entertainer and musician known as Samaita Zindi was one of reggae’s most successful contributors to its growth and development in Zimbabwe. He began his career at the age of nine when he learned how to play the guitar. On leaving school, he went to Harare where he played with several bands before going to England in the late 1970s .

In London, Samaita teamed up with some Jamaican musicians and this is when the reggae bug began to spread in him. In 1980, Bob Marley had just returned from Zimbabwe where he had performed at the independence celebrations. Samaita and I forced our way back stage at Reggae Sunsplash, which was being held in Crystal Palace, to greet Marley and we introduced ourselves. “So you two are musicians? When you go back to Zimbabwe, go and spread the reggae message. I have just come from Zimbabwe and reggae is still a strange kind of music to many people there. Jah will give you guidance and protection,” Marley said.

On return to Zimbabwe, Samaita was determined to start a reggae outfit. He teamed up with some youngsters in Glen Norah whom he coached to play reggae. He called the band Samaita. People often wonder how Nicholas Zindi ended up with the name Samaita. This came out of the Zindi totem, Samaita, and he found it appropriate to name his band after his totem. Although the band did not last long, he was stuck with that name till his death.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

In came his second band in 1985 called Novismos (an acronym for No Visual Means of Support), where he was joined by another reggae enthusiast known as Ashanti. Together they recorded the single Mvura Ngayinaye.

Novismos lasted two years. The band was living rent-free at a squat in Mabelreign until they were evicted by the owners of the house. That also closed shop for the group as the musicians were now scattered all over.

Next was Transit Crew formed in December 1988. Joseph Brown aka Munya Brown — a Jamaican Rastaman — who had originally come to Zimbabwe with Misty-In Roots Band from London in 1982, returned to the country to stay because he had married a Zimbabwean girl, Anna Brown. To keep himself busy, he joined the band Ilanga, but Ilanga was not forthcoming with the reggae direction he wanted to go. So, he decided to form his own band. He asked me to gather some musicians for him and, of course, I delivered Samaita who I thought had a lot in common with Munya Brown. Along with him came Munya Nyemba, Temba Jacobs, Anthony Liba Amon, Emmanuel Frank and Tendai Gamure aka Culture T.

Transit Crew became a life-long commitment for Samaita. By the year 2000, Samaita with Transit Crew had recorded three albums, namely, Sounds Playing, The Message and Money. The albums were well-received nationally and internationally and helped to establish Transit Crew as a formidable reggae outfit. It is on the strength of these albums that visiting Jamaican artistes such as Luciano, Yasus Afari, King Sounds and Sizzla Kalonje came to Zimbabwe without their backing bands and used Transit Crew as backing musicians for their performances. It is also on the strength of these three albums that Transit Crew were invited to do a six-month stint in Japan although Samaita did not go due to difficulties in obtaining a passport in time. His passport had long expired while he was still in the UK. Instead, Themba Jacobs, a guitarist, reggae enthusiast and a South African refugee who was living in Zimbabwe at the time and later became a reporter on South Africa’s SABC, replaced him.

After a short break from the band in 2006, Samaita went on to study for a degree in Jazz at the Zimbabwe College of Music where he learned to read and write music.

In 2009, back with Transit Crew, they recorded the album titled Unity at Clive “Mono” Mkundu’s Monolio Studios. Up to this day, this album is still in demand. Even in Jamaica, those who have listened to it, people like Tony Rebel, Sizzla, Capleton and others, think that it was done by Jamaican musicians.

Samaita was a humble, kind, caring and positive person. In his spare time he organised music festivals under the banner of the Zimbabwe Union of Musicians (ZUM) to which he was a member of the executive together with Michael Sekerani and Robson Nyanzira. He was also on the board of the Zimbabwe Music Rights Association (ZIMURA) between 2005 and 2007. With assistance from Webster Shamu, who was ZUM’s patron, he managed to get 100 housing stands for musicians at Hopley, where several musicians such as Noel Zembe, Forward Mazuruse, Weeds Mbale and others benefited and built their homes.

Samaita was also instrumental in coaching several Transit Crew vocalists such as Culture T, Emmanuel Frank, Mike Inity, Mannex Motsi, Rootsman Spice, JehFari, Cello Culture, Rungano Chaza and Destiny.

True to Marley’s words, Samaita followed his instructions till death. He never departed from the reggae genre even when in later years, Zimdancehall became the trending genre in Zimbabwe, he stuck to conscious roots rock reggae.

Samaita followed the Rastafariam philosophy to a large extent. From 1983, way after Marley’s death, he started growing dreadlocks and in no time at all they had grown to his waist. He stopped shaving his beard. He explained that this was in keeping with the covenant with Jah.

He started preaching about Jah Rastafari, the Most High. He talked about love, peace and harmony and addressed every black woman he met as Empress in keeping with his Rastafarian philosophy. In his preachings he often spoke about resisting Satan’s temptations through embracing Rastafarian spirituality. And, of course, to become more creative he recommended the use of herbs from the Most High, which he called sensimillia. He would often sing A Black Man Redemption and Chant Down Babylon.

Tragically, Samaita’s career was cut short when he died from complications caused by prostate cancer. Over a thousand mourners attended his funeral and he became the second entertainer to be buried at the new cemetery in Chitungwiza, Zororo Memorial Park, after Lawrence “Bhonzo” Simbarashe.

Condolence messages came from as far afield as Australia, the United Kingdom, Norway, the US, Jamaica and South Africa.

Samaita was committed to family life as evidenced by the way he often spoke about how he wanted to provide for his wife, Annamore Chimedza-Zindi and his three children Mukai (25), Chiedza (22) and Tongai (18).

He was a true brother; cool, calm and collected. Reggae music’s loss is immeasurable. The immortal voice and the ideals he cherished will remain with us forever. Words are a scant tribute when death strikes. We will forever miss Samaita Zindi.

Feedback: [email protected]