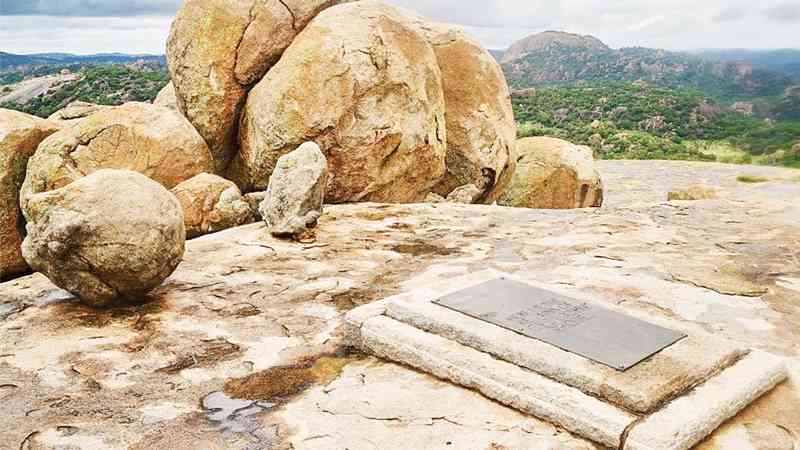

THE grave of Cecil John Rhodes is controversial in Zimbabwe.

Some want the grave removed from its site in Matobo National Park, Matabeleland South province.

Others believe that history and economy trump current politics.

It’s a sacred hill where for centuries Zimbabweans would go to consult their ancestors.

It’s also where the notorious British coloniser Rhodes chose to be his final resting place.

The white supremacist died more than 120 years ago in South Africa aged 48 after carving out swathes of territory for the British empire.

Part of the land grab, later named Rhodesia in his honour, included modern Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Nestled in the Matobo National Park, his grave is simple, with “Here lie the remains of Cecil John Rhodes” engraved on it.

- NBA Playoffs: Curry gets the Warriors to semis

- Climate action project builds new narratives

- DJ Ladyg2 fights stereotype in showbiz

- Hebrew scriptures: Can we still believe in a soul?

Keep Reading

Part of the younger generation wants his remains removed to rid the country of the last vestiges of colonialism.

But the grave attracts tourists who bring much-needed income for surrounding villages — and many local people oppose any exhumation.

Located atop a steep hill immersed in lush vegetation, a short climb is necessary to reach the grave, which is surrounded by imposing rocks rounded by erosion.

The stones are covered in light green aniseed and orange lichens that brighten at the slightest touch of the sun.

From the hilltop, visitors gaze at the vast expanse of trees around, where antelopes and warthogs roam.

Clouds roll across the tranquil horizon while birds chirp in the silence.

The younger generation wants it removed to rid the country of the last vestiges of colonialism.

In South Africa, students at the University of Cape Town launched a “Rhodes-Must-Fall” protest in 2015, initially to pull down Rhodes’ statue at the campus.

It later morphed into a global campaign, which saw Oxford University resisting calls to remove a statue of the politician — placing an explanatory panel next to it instead.

Often described as a philanthropist but also an arch-racist, Rhodes dreamt of a British Africa from Cape Town to Cairo, with the blessings of Queen Victoria.

Cynthia Marangwanda (37), from Harare, is enraged by the presence of Rhodes’ grave.

She believes he chose that site because he knew its spiritual significance to the local people.

It was his “final display of power, a deliberate and calculated act ... of domination”, said the activist.

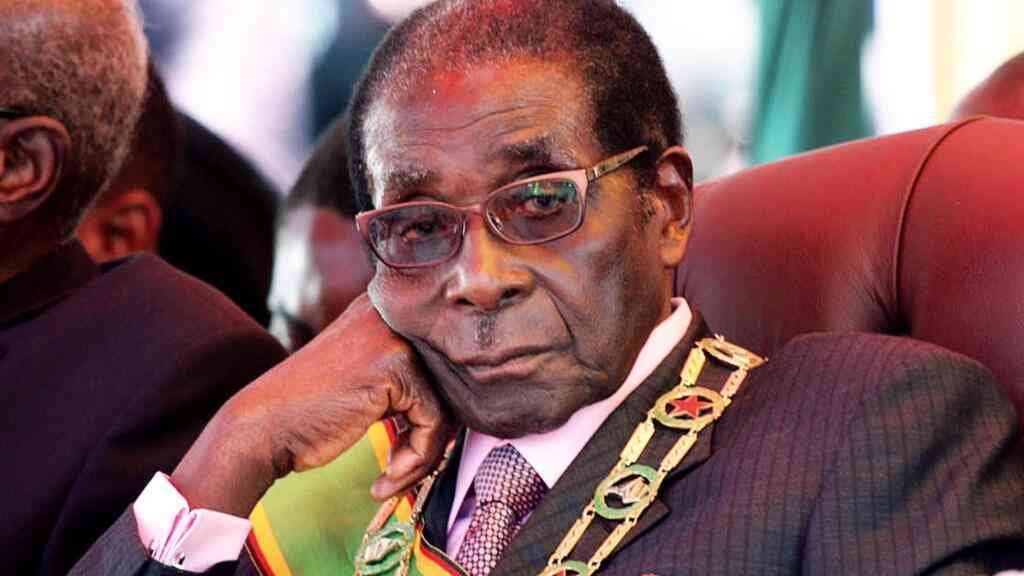

Zimbabwe’s ex-strongman Robert Mugabe, who took the reins from independence from Britain in 1980, saw no reason to remove Rhodes’ remains.

But Marangwanda has been energised by the current President, Emmerson Mnangagwa, who “understands the significance, the heritage aspect of the debate”.

Even so, more than five years after Mnangagwa came to power, there is no indication of movement on the issue — or consensus on where the remains would go.

The economic benefits accruing from the tourism, do not hold water for Marangwanda.

“Matobo is such a beautiful landscape, it doesn’t need this colonial grave” to attract foreign visitors, she stressed.

The presence of the grave in Zimbabwe is an “insult to our very existence as a people”, said historian and co-founder of RhodesMustFall campaign Tafadzwa Gwini (33).

Exhuming the remains “is a form of reclaiming our identity as a people”, insists Gwini.

Yet some visitors simply don’t understand the outrage around the grave.

“I brought my kids. I also came here as a kid,” said a 45-year-old white Zimbabwean, Nicky Johnson.

Johnson added: “History shouldn’t be tampered with. He wanted to be buried here, that’s how it should be.”

Akhil Maugi (28), who lives from nearby city of Bulawayo, shares similar sentiments.

“You can’t erase what happened. No one would come here if this grave was gone,” he said.

Pathisa Nyathi, a 71-year-old local historian, points out that it was “the grandeur of the rocks” that made it a “holy site” that once attracted pilgrims from neighbouring countries.

The “pre-eminent shrine” in the region “was sacred to Africans”, but not to Rhodes, said Nyathi.

Opposition MP and ex-Education minister David Coltart, who regularly cycles in Matobo Park, brings some humour to the debate saying: “I must say Rhodes had an incredible eye for real estate.”

Exiting the park, is a roadside market selling T-shirts, woven baskets and carved animals to tourists.

A little further is a village with a few houses.

Micah Sibanda (82) stands barefoot, leaning on a walking stick, overlooking a few cows.

Rhodes’ grave is “important” to the villagers because it attracts visitors who in turn buy crafts “and we get some money to send our kids to school ... get food and clothing”, said Sibanda.

If the grave is removed, it “will be very painful for us”.

After all, Sibanda said, the white visitors are also coming “to pay respects to their own ancestor”.