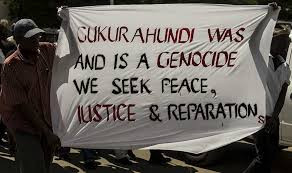

In 2018, President Emmerson Mnangagwa pronounced that it was now possible to talk about the Gukurahundi era.

Cautious hope stirred for many victims that finally they could overcome silence to discuss this terrifying time that remains unexplained and not fully acknowledged: they could also raise the long reach of this violence, whose consequences still impact today.

Perhaps there would finally be reparation and truth.

However, for other victims, skepticism remained. Some who suffered the murder of relatives and days of brutal torture and humiliation, have previously given personal testimony – to churches or civic groups, and to the various token state efforts over the years, without any resulting benefit, and without these testimonies being acknowledged and integrated into official national history.

The first half-hearted state effort was during the Government of National Unity, 2009-2013, when the Organ for National Healing, Reconciliation and Reintegration (ONHRI) was tasked with the matter of ‘healing’ victims in Zimbabwe.

However, one of the three ministers of ONHRI was subsequently arrested at a memorial service for Gukurahundi victims in Lupane: he never received an apology for this, nor support from his fellow ministers.

Underfunded and clearly not really intended to achieve anything, ONHRI fell apart after this, achieving little.

The adoption of a new constitution in 2013 included the creation of a National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC).

- Mr President, you missed the opportunity to be the veritable voice of conscience

- ED to commission new-look border post

- Zanu PF ready for congress

- EU slams Zim over delayed reforms

Keep Reading

However, the NPRC remained inactive for several years of its ten-year term, as the state dragged its heals in appointing commissioners, and then in passing legislation to empower the NPRC to undertake activities.

The NPRC Act was eventually signed in 2018. Together with civics and victim groups, the NPRC agreed that Gukurahundi was the most important issue to “resolve”, being considered the root of subsequent eras of violence and impunity in Zimbabwe.

However, once more lack of resources and the fact that it took years to set up offices in Bulawayo, hampered any meaningful roll-out of activities.

The two commissioners in Matabeleland nonetheless showed a willingness to work with victims, including on the issue of exhumations of those buried in school yards, antbear holes, shallow and mass graves all over Matabeleland.

However, once their terms of service ran out, a new cohort of Commissioners chose to limit their mandate to preventing future election violence.

There was no more activity from the NPRC with regard to Gukurahundi.

The reason given was that the Chiefs of Matabeleland were mandated to deal with Gukurahundi instead of the NPRC. In 2024, the NPRC ceased to exist, its ten-year mandate having expired.

So, the chiefs of Matabeleland, several coming from families victimiszed in this era, now bear the terrible burden of “resolving” Gukurahundi. We have worked closely with the chiefs over the last few years, choosing to use our decades of experience with victims to take part in the official state training of chiefs, rapporteurs and mental health first aiders, for these proposed village hearings.

This earned us vitriol from some, who viewed us as having aligned with one more futile and half-hearted process, but we felt a great responsibility to support the process in any way we could – for the sake of any victims who may come forward to testify, and for the sake of the chiefs, who were being asked to step outside their usual hierarchical role, to offer consolation and healing to this country’s most vulnerable.

In relation to any proposed programme working with victims, we feel a responsibility in trying to ensure victim-centredness, to protect victims from more harm.

The training process has now stretched to years, with long intervals, and no clear indication of when village hearings will begin. .

At this point, there has not been any official village hearing. In the meantime, some of those trained as rapporteurs or mental health first aiders, have died, or left the country.

It appears that the hearings are continuously pushed to the bottom of any state budget: as they are not mandated in any official way, this is easy to do.

Multiple reports in the media in 2024 stated that hearings were about to begin the following month, and the following month.

Again, in 2025, it was stated that the hearings would roll out in March, yet in May the chiefs themselves are no clearer on when the village hearings will begin.

Over the last two years, the chiefs have been repeatedly talking about and encouraging people to come forward to the village hearings when they start, but after two years of doing this, the Chiefs themselves are now being considered incredulously by villagers.

Where are these hearings? Every day victims die unheard. And in the meantime, the historical revisionism that is taking place across the country is appalling.

I have been told in Harare that the “Ndebeles triggered” what happened to them - that the Ndebeles were about to commit genocide against the Shonas in 1982 and had to be stopped!

Therefore, whatever happened was their fault. When one deals with the actual atrocities that unfolded on the ground, my heart breaks to think that such a distorted, false version of history is taking hold.

How did rural civilians in remote areas ‘trigger’ this terrible era of torture and its consequences?

Furthermore, since 2018, no fewer than four attempts to place memorials to the dead at Bhalagwe Camp, and in the Midlands, have been destroyed, including by the use of dynamite and bulldozers.

How is this in keeping with the pronouncement that Gukurahundi can now be talked about? If remembering and memorializing are met with such force, should victims feel safe to speak out?

Remembering can indeed be perceived as subversive: political control is rooted in particular versions of history and conquest, which must not be challenged by alternative narratives.

Orwell’s dictum that ‘who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past’, is threatened by alternative memories.

Zenzo Moyo has previously in this column spoken to the Zanu PF desire for a one-party state that predated even the first election in 1980.

Getting rid of Zapu and its supporters was a long-standing ambition of Zanu PF leadership, and the terms “Zapu-supporter”, “Ndebele” and “dissident” became deliberately conflated in the early 1980s.

This desire for a one-party state triggered the training of an army unit that was already agreed to by Robert Mugabe and the North Koreans in August 1980.

This was before any instability in post-independence Zimbabwe. The “Gukurahundi Brigade” was necessary for the one-party state.

It is in the interests of all Zimbabweans that the village hearings should take place as soon as possible, and also that the reality of Gukurahundi should become integrated into national history, along with a deeper understanding of how the colonial era, and the violence and internal disputes of the war of liberation, led the nation to where we are now.

The trauma of those years has already become intergenerational, and we need to heal the past in order to integrate Matabeleland into a truly national, Zimbabwean future.

For that, we need both truth, and reparation for victims.

*Dr. Shari Eppel, writing in her individual capacity.