ZIMBABWE’S struggle with poverty and hunger is inseparable from its struggle with energy access.

From rural homesteads to smallholder farms and informal markets, energy shapes how food is produced, processed, stored, and prepared. Yet energy remains one of the most unevenly distributed resources in the country.

For millions of rural households particularly women, energy poverty is not an abstract concept but a daily burden that deepens food insecurity, reinforces gender inequality, and limits economic opportunity.

If Zimbabwe is serious about ending hunger and lifting people out of poverty, sustainable energy must be placed at the centre of its development agenda.

Women sit at the heart of Zimbabwe’s food systems. Globally, women make up over 37% of the rural agricultural workforce, rising to 48% in low-income countries.

They account for nearly half of the world’s small-scale livestock managers and a similar share of labour in small-scale fisheries, according to FAO’s Policy on Gender Equality (2020–2030).

Zimbabwe reflects these global patterns. Women dominate smallholder agriculture, informal food markets, and household food preparation.

Paradoxically, they are also more likely than men to experience food insecurity in every region of the world.

- Village Rhapsody: In Zimbabwe poverty is biting the poor the most

- Zim maize output to drops by 43%

- Village Rhapsody: In Zimbabwe poverty is biting the poor the most

- Zim maize output to drops by 43%

Keep Reading

This contradiction exposes a structural failure, those who produce and prepare food are often the least empowered to access the resources especially energy that could transform their productivity and livelihoods.

Energy poverty, defined as the lack of access to modern, reliable, and affordable energy services, disproportionately affects rural women.

The 2018 FAO report Costs and Benefits of Clean Energy Technologies in the Milk, Vegetable and Rice Value Chains highlights how traditional gender roles and women’s limited asset base intensify this burden.

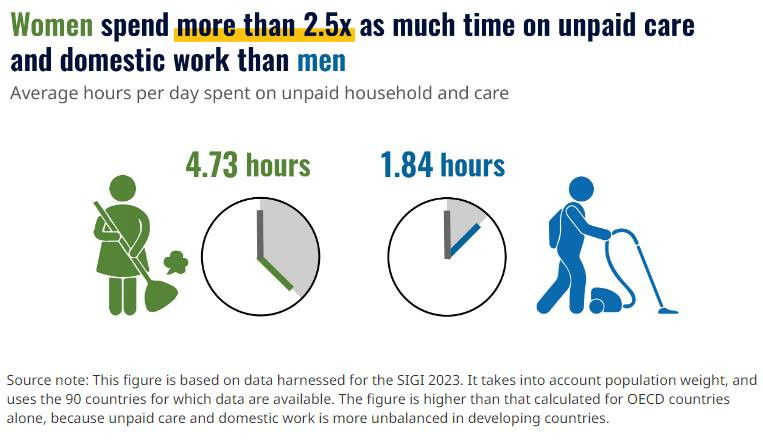

Women work longer hours per day than men and spend more time on unpaid, labour-intensive, and repetitive tasks.

In Zimbabwe’s rural areas, women and girls are primarily responsible for collecting firewood, fetching water, and gathering fodder.

These tasks consume hours each day time that could otherwise be spent on education, income-generating activities, or rest.

Sustainable energy has the power to disrupt this cycle.

Access to clean cooking technologies can reduce the time spent collecting firewood and lower exposure to indoor air pollution, which is a major cause of respiratory illness among women and children.

Solar-powered water pumps can replace manual water collection, freeing women’s labour while improving irrigation and crop yields.

Renewable energy for milling, refrigeration, and agro-processing can reduce post-harvest losses, increase value addition, and stabilise incomes for smallholder farmers.

These are not marginal gains; they are transformative changes that directly link energy access to food security and poverty reduction.

However, technology alone is not enough. Many promising energy interventions fail because women the primary users are excluded from decision-making.

When women are shut out of planning, financing, and governance processes, energy solutions often do not reflect their real needs or constraints.

FAO’s work to amplify women’s voices at societal and structural levels is therefore critical.

Women understand better than most the energy needs of their homes, families, and farms.

When their perspectives shape design and implementation, energy services are more likely to be adopted, maintained, and sustained across agricultural value chains.

The link between women’s empowerment, energy, and nutrition is especially important in Zimbabwe, where childhood malnutrition remains a persistent challenge.

When women increase the income they earn and control at home, in institutions, and within their communities they tend to invest more in their families’ well-being than men.

This includes spending on diverse diets, healthcare, and education.

Sustainable energy can accelerate this virtuous cycle by enabling women-led enterprises, improving productivity, and reducing unpaid labour. In doing so, it strengthens household food security and improves nutritional outcomes for children.

Sustainable energy is also essential for climate resilience. Zimbabwe is already experiencing more frequent droughts, erratic rainfall, and extreme weather events.

Renewable energy solutions such as solar irrigation, biogas, and off-grid power systems support climate-smart agriculture while reducing dependence on expensive and unreliable fossil fuels.

For smallholder farmers, particularly women with limited access to credit, decentralised renewable energy offers a practical pathway to adapt to climate shocks without deepening debt or environmental degradation.

Yet significant barriers remain. Upfront costs for clean energy technologies are often prohibitive for rural households.

Women’s limited access to land ownership, finance, and collateral further restricts their ability to invest in energy solutions.

Addressing these constraints requires deliberate policy choices: gender-responsive financing, targeted subsidies, inclusive extension services, and community-based ownership models that recognize women as both users and leaders.

Energy planning must move beyond national grids and urban centres to prioritize off-grid and mini-grid solutions tailored to rural realities.

Ultimately, sustainable energy is not just about kilowatts and infrastructure; it is about power in the social sense, who has it, who controls it, and who benefits from it.

In Zimbabwe, expanding access to sustainable energy can help dismantle the structural inequalities that keep women poor and hungry despite their central role in food systems.

By investing in women-centred energy solutions, the country can unlock gains in food security, nutrition, education, and economic resilience that ripple across generations.

Lifting people out of poverty and hunger in Zimbabwe will require integrated solutions that recognise the interconnectedness of energy, gender, and food systems.

Sustainable energy, designed and governed with women at the centre, offers one of the most powerful levers for change.

Ignoring this link would mean perpetuating a cycle of deprivation.

Embracing it could help build a more equitable, nourished, and resilient Zimbabwe.

*Gary Gerald Mtombeni is a Harare based journalist. He writes here in his personal capacity. For feedback Email [email protected]/ call — +263778861608