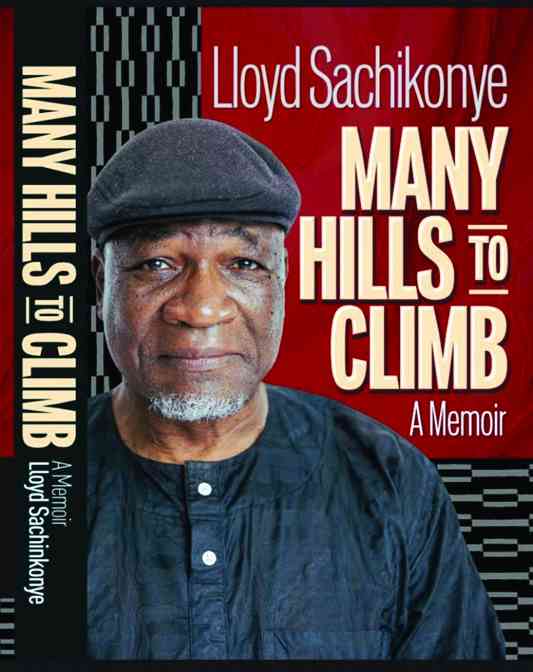

Lloyd Sachikonye’s recently published memoir, Many Hills to Climb, is far more than a recounting of one man’s life—it is a walk through the emotional, political and intellectual terrain of Zimbabwe and Africa over the last seven decades.

The title of the memoir itself signals the journey ahead: steep, layered, often difficult, yet profoundly shaping. In this deeply reflective narrative, history does not remain trapped in abstract textbooks; it lives, breathes, and walks in human shoes—his.

Lloyd Sachikonye is a Professor Emeritus of Governance and Development Studies. He was born in Zimbabwe where he received his early education before attending universities at Zaria in Nigeria and Leeds in the United Kingdom. Prof Sachikonye researched and taugh Governance and Development Studies at the University of Zimbabwe for 33 years.

In the book,from the outset, Sachikonye situates his life within a continuity of ancestry, culture, and place. On page 19, he quotes the proverb, “To forget one’s ancestors is to be a book without a source, a tree without a root,” setting the tone for a memoir grounded in memory and lineage.

By beginning with his forebears from the Mutasa clan of the Manyika people (as seen on pages 20–22), he reminds readers that African identity is not merely personal but communal, historical and territorial. This rooting in heritage provides a powerful counter-narrative to colonial attempts to sever Africans from their past.

Growing up in colonial Southern Rhodesia, Sachikonye’s childhood reflects a period defined by racial segregation, limited opportunities, and the everyday humiliations of minority rule. Yet, from these constraints emerged a determination to learn, to understand, and ultimately to resist.

His story mirrors the journey of many Zimbabweans whose early lives were shaped by colonial injustice but whose spirits were sharpened by the struggle for liberation.

One of the strongest and most moving dimensions of the memoir is his tribute to the fallen—friends and comrades like Paul, Simon “Masiwa,” and Kudzanai, remembered on page 4. Their absence haunts the narrative and embodies the real cost of Zimbabwe’s independence. Here, Sachikonye does not romanticise war; instead, he humanises it by recalling the young men who never came home. In doing so, he anchors national history in personal sacrifice, reinforcing the idea that freedom’s price is measured in lives, not slogans.

- When history walks in human shoes: A review of Sachikonye’s Many Hills to Climb

- Many Hills to Climb: Why Lloyd Sachikonye’s new memoir matters now

Keep Reading

As the memoir progresses, Sachikonye’s intellectual journey becomes a central theme. Education becomes both refuge and weapon—an escape from structural limitation and a tool for social transformation. His path from village schooling to global academia reflects a wider African experience: the pursuit of knowledge as a means of reclaiming dignity and agency. The author writes of knowledge as power, warning that while power can corrupt, knowledge provides the checks and balances that societies needs. In a Zimbabwe still grappling with governance and accountability, this message resonates sharply.

The memoir also documents the tumultuous period of structural adjustment, globalisation, and political upheaval. In the book, Sachikonye describes how globalisation reshaped economies and identities, often unevenly and unjustly. His generation—caught between the ‘colonial era’ and the ‘independence era’—lived through tectonic shifts in political and social order. For many Africans, this period represented both the promise of opportunity and the pain of dislocation. By situating his coming-of-age within these global forces, Sachikonye offers readers a textured understanding of how individual lives are shaped by systems beyond their control.

A recurring motif in the memoir is the tension between hope and disillusionment. Independence brought euphoria, opportunities and a sense of self-determination. But, as the years unfolded, new struggles emerged—political repression, economic meltdown, and widening inequality. Yet even in his critique, Sachikonye avoids bitterness. Instead, he advocates for justice, integrity and democratic principles grounded in evidence and historical awareness.

His fight—conducted not with weapons but through research and writing—echoes a broader African intellectual tradition that seeks to hold power accountable and defend the dignity of ordinary people.

Nature, place and landscape also play a symbolic role in the memoir. The vivid descriptions of the eastern highlands—Nyanga, Bonda, Mutasa—and the rivers and mountains of his childhood create a sense of continuity even as political eras change.

These landscapes stand as witnesses to history, outlasting the empires, ideologies and leaders that rise and fall. They remind the reader that while human beings may struggle through many hills, the land remains a constant, binding generations together.

Perhaps the greatest strength of Many Hills to Climb is its balance of the personal and the political. Sachikonye does not present himself as a hero, but as a participant-observer of history—one who has lived its impacts and sought to understand them. His reflections on identity, community, governance and justice transcend the boundaries of memoir and venture into philosophy and civic morality. The book is not merely about what happened in his life; it is about what his life reveals about Zimbabwe, Africa, and the human condition.

In walking through Sachikonye’s hills, readers are reminded that history is never abstract. It is lived in bodies, carried in memory, spoken in languages, shaped in villages and cities, and inscribed in the joys and traumas of ordinary people. For Zimbabwean readers, the memoir offers both recognition and reflection—an echo of their own histories and a challenge to consider the future with honesty. For African readers, it contributes to the broader narrative of a continent still negotiating the legacies of colonialism and the complexities of self-rule.

Ultimately, Many Hills to Climb is a generous, wise and necessary book. It teaches that while the hills of life may be many, they are climbable—if one carries with them the tools of memory, courage, knowledge and hope. In telling his story, Sachikonye invites us to walk alongside him, to feel the weight of history in human shoes, and to recognise that the journey of a nation often begins with the journey of one life.

The book is available at Innov8 bookshops across the country and interested readers can reach the author on +263772242850

Fungayi Antony Sox is literary champion, communications and publishing specialist with a decade of experience working with authors,creatives, brands and organisations across sectors. For feedback email him on [email protected] or contact him on +263 776 030 949.