HARARE — Austin Mushanguri shakes his head in dejection and walks away from the fridges in an affluent supermarket in the capital after reading a sign saying he can only buy one bottle of beer instead of the dozen he’d hoped for.

Similar scenes are playing out across the country where foreign-exchange shortages and austerity measures have left consumers facing long lines for everything from fuel to bread, sugar and cooking oil.

It’s the latest challenge to President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s newly-elected government that’s trying to rebuild an economy wrecked by the misrule of former president Robert Mugabe.

“How do they expect me to queue in the shops over 12 times to buy a single bottle of this beer?” Mushanguri, 41, asked. “This not what we voted for, this is not what we expected after elections.”

Zimbabweans were optimistic about an economic revival when the military ousted Mugabe in November last year after almost four decades in power.

That’s going to take time and will “entail pain and the need for sacrificing short-term gains for longer-term prosperity”, according to Finance minister Mthuli Ncube, who Mnangagwa appointed last month to attract foreign investment, reduce mass unemployment and narrow a gaping fiscal deficit.

Among measures Ncube introduced last week to stabilise the economy was a tax increase on money transfers. The announcement triggered a rise in basic-commodity prices, stoking fears of an inflationary spiral and leading to long queues forming at fuel stations.

Many shops, under pressure from the government, are restricting customers’ purchases to prevent hoarding and ensure everyone gets something.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Others have gone further: Yum! Brands Inc temporarily shut some of its KFC outlets this week, saying it couldn’t find enough dollars to pay suppliers.

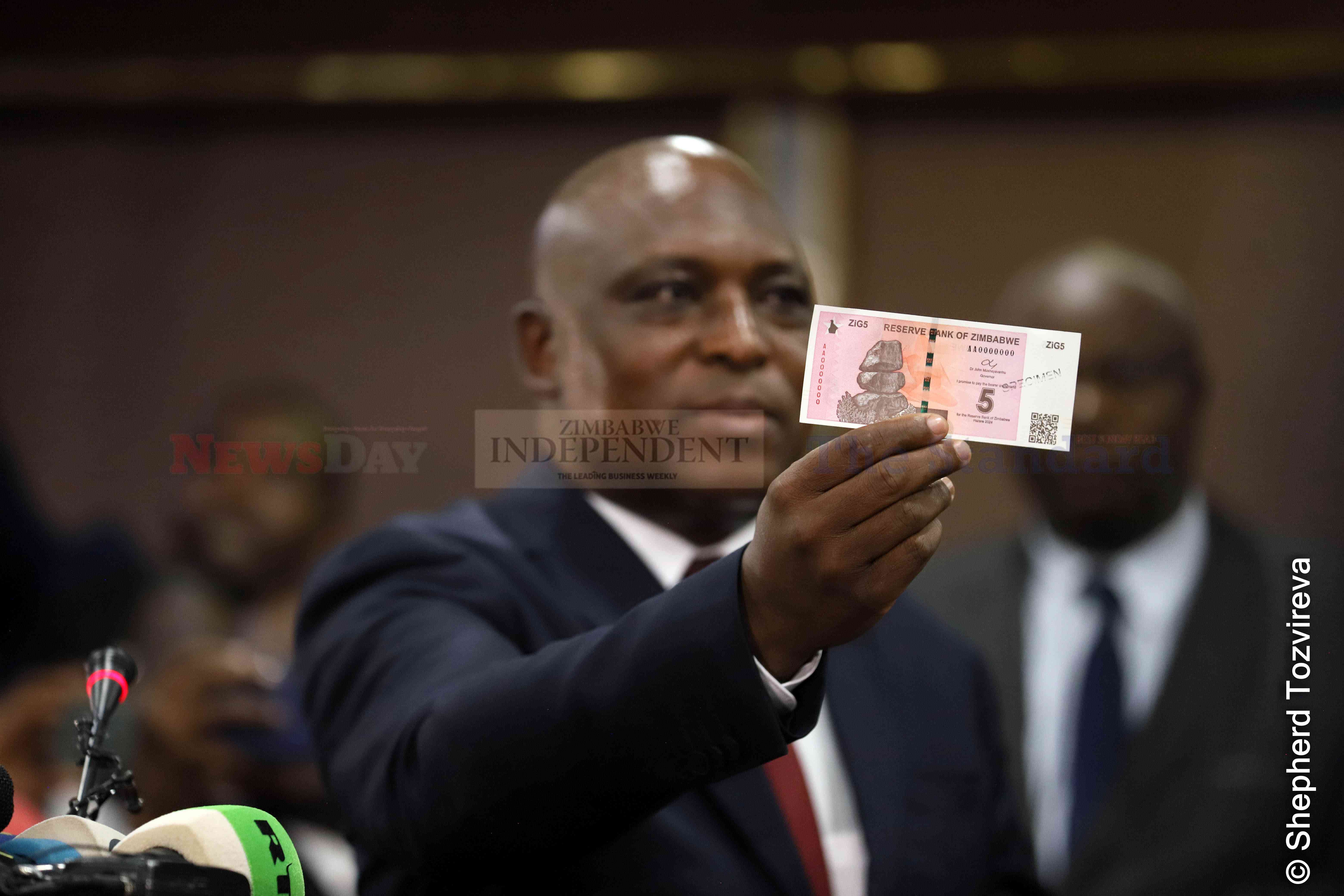

The country’s quasi-currency, known as bond notes, has plunged in value.

Bond notes were introduced two years ago and were meant to represent the value of one dollar.

Zimbabwe, having scrapped its own worthless dollar to end 500 billion-percent inflation in 2009, accepts them and the greenback, euro and rand, among others, as legal tender.

In Zimbabwe’s skewed markets, rising share prices are — like in Venezuela — a sign that stresses are building in the financial system.

Local traders pile into equities when bond notes depreciate and they think inflation will accelerate. It’s forced foreign investors including Franklin Templeton, JPMorgan Chase & Co and Allan Gray — who can’t repatriate their money because of strict capital controls — to write down the value of their assets.

“The spike in stocks is an inverse mirror of the local shortage of dollars,” Hasnain Malik, Dubai-based global head of equity research at Exotix Capital, said in a note to clients last week.

The dearth of foreign currency is making life tougher for Zimbabweans.

“We are now charging 20 real dollars for an X-ray, or 100 bond notes,” said Itai Chamunorwa, who works at a private surgery in Harare. “We’re just following what others are doing.”

Other businesses have stopped accepting bonds notes or electronic payments — which are even less valuable than the notes — altogether, and will only take hard cash.

Central bank governor John Mangudya said last week that Zimbabwe had enough foreign exchange to pay for imports of fuel, wheat and other items.

The crash in bond notes is caused by “opportunists” trying to sow “unnecessary panic and despondency”, he said.

Mnangagwa (76) has urged calm.

“We must all be realistic,” he wrote on Twitter. “There are no silver bullets or quick fixes. There is no need to panic. The government is guaranteeing the availability of all essential commodities.”

Zimbabweans are yet to be convinced, according to John Robertson, an economist in Harare.

“It’s all about the lack of confidence in the government’s ability to resolve problems,” he said. “People easily panic. It’s become a psychological problem rather than one of economic sense.”

For Mushanguri, the beer-drinker, it’s a far cry from what he thought would happen after the elections.

“All those high hopes we had are fading fast,” he said — Bloomberg