BY ALEX MAGAISA

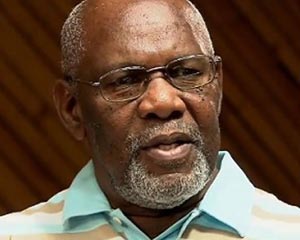

Following the death of Dumiso Dabengwa, Zimbabwe has lost a true hero. That he is a national hero requires no deliberation.

For none among the living have the legitimacy to make that pronouncement. It is a matter of fact.

He carried himself with quiet dignity and after a reluctant and ultimately fruitless dalliance with Zanu PF following the Unity Accord, Dabengwa let his conscience be his master and returned to the people, in whose hearts and minds heroes lie.

He walked with them until he drew his last breath, refusing the lure of the gravy train, a temptation that few men have the capacity and will to resist.

He could have chosen the comfort of the ruling party to curry favour with the establishment in his final years.

But ever the humble man, Dabengwa chose to remain with the people — an extraordinary man who chose the path of ordinariness because it was the right thing to do.

I got to know more about the life and tribulations of Dumiso Dabengwa when I was a law student at the University of Zimbabwe.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

In those days, students of constitutional law were required to read cases in which Dabengwa and his comrade, Lookout Masuku, a liberation war commander, were the accused.

Few men epitomise in their experiences the contradictions and ironies of the liberation struggle and its aftermath.

These days people are familiar with the routine use of instruments of the state and the law to harass and intimidate political opponents.

But in the early 1980s, when there was still great euphoria of independence, many in Matabeleland and Midlands provinces were traumatised and living in fear.

Dabengwa and Masuku were not the only victims of unlawful arrests and detention for political reasons.

But they were the most high profile. That period is now known universally as Gukurahundi.

Dabengwa and Masuku were among the great war heroes.

Both were members of the Zipra War Council, the supreme body of the Zapu military wing. The others were Akim Ndlovu, Alfred Mangena, and Samuel Munodawafa.

Masuku commanded Zipra, taking over from the late Alfred Nikita Mangena, while Dabengwa was the intelligence supremo.

He was known to many as “the Black Russian” — in reference to his Russian KGB training. While Zanu was close to China, Zapu was more proximate with Russia.

Zapu also worked very closely with the ANC, launching operations together with Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK) including the Wankie campaign.

Such landmark operations are under-reported in a liberation narrative which tends to disproportionately favour Zanla at the expense of Zipra.

When the liberation forces returned to the country, Dabengwa and Masuku were among the men chosen to guide and facilitate the smooth integration of the two liberation armies and the Rhodesian security forces.

They were both generals in the Joint Military Command, which led that effort.

The integration was a delicate and sensitive task which required strong and wise leadership.

There were great challenges including battles between the former liberation forces.

It was men like Dabengwa who helped calm things down, showing great leadership.

“They both regularly visited the camps and tried to reassure the lads that their interests were being looked after in difficult circumstances,” wrote Nkomo in his autobiography.

They had “played their full part in the building of a national army… when fighting broke between Zipra and Zanla they had bravely faced it, and been chiefly responsible for pacifying their own men.

“They were loyal citizens and able professional soldiers.”

A High Court judge, Justice Hilary Squires, who presided over a key treason trial, commended Nkomo, Dabengwa and Masuku for the leadership they had shown in the integration process, refuting accusations that they were inclined to overthrow the Mugabe government.

He said, according to the New York Times, their attitude and actions were “the antithesis of people scheming to overthrow the government’’.

Despite their sterling efforts in rebuilding and integrating the new military force during that sensitive transition from the war years, it did not take long before their former comrades turned against Dabengwa and his ex-Zipra cadres.

Both Dabengwa and Masuku were accused of plotting to overthrow the government.

Dabengwa faced the charge of treason on the basis of a letter he had allegedly written to the Soviet intelligence.

Masuku was now a Lieutenant General and a deputy commander of the Zimbabwe National Army.

Dabengwa had left to set up a business and, according to Nkomo, was “doing very well” — an indication perhaps that for Dabengwa politics was never the natural or preferred career.

He had performed his role and was ready to pursue a career in business.

However, these plans were put in jeopardy when in 1982, Dabengwa and Masuku were arrested along with other senior former Zipra officials and charged with treason and associated offences.

The Mugabe government claimed arms caches that had been “discovered” at farms owned by Zapu (Ascot and Hampton Ranch) were planted by the accused and their accomplices.

In short, Dabengwa, Masuku and others were being accused of plotting to topple the government.

Nkomo and senior Zipra colleagues in the government were sacked.

Younger readers will find this familiar and realise that these charges against political opponents have always been part of the authoritarian script.

Even as we commemorate Dabengwa’s life, recounting his trials and tribulations, five young Zimbabweans are in detention, charged with attempting to topple the government.

Like Dabengwa and Masuku, they are also at Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison, being treated like common criminals even before trial.

Many more before them have faced similar charges. If anything, they are walking a path upon which illustrious sons and daughters have walked before.

If there is any consolation, it is that their suffering will not be in vain. Ian Smith had used similar strategies during the colonial era to no avail.

After independence, the Mugabe government kept emergency laws which had been used against the nationalists by the Smith regime.

A key tool under that regime was “preventive detention” which allowed the state to detain an individual indefinitely without trial for purposes of preventing conduct that would breach public order and safety.

It’s a blunt instrument, which is easily abused by authoritarian regimes against perceived opponents. And the use of similar laws by the current government does it no favour at all in the eyes of the world.

Arresting people in order to investigate is both cowardly and immoral.

After the arrests, Dabengwa, Masuku and others were kept in detention and oft-times in solitary confinement.

They were put on trial at the High Court in early 1983 after which they were acquitted.

However, in a clear abuse of the law, they were re-arrested and detained just outside the courtroom, as supporters celebrated their acquittal. This is how the New York Times described the moment in 1983:

“They did not know that moments before two plainclothes officers had crossed an open yard adjacent to the courtroom and handed a typed order through the bars on the room in which the six acquitted men were still being held, informing them that they were being detained again.”

They were detained on virtually the same grounds and under the same emergency laws. It was as if the trial and acquittal had never happened.

While the court had found that the arrest and detention of Dabengwa and Masuku were without foundation and, therefore, unlawful, the conduct of the state had actually raised the risk of conflict by generating more insecurity and resentment among the ex-Zipra cadres.

Already feeling excluded and marginalised following Zanu’s election victory in 1980 and political domination, some ex-Zipra forces saw the detention of their commanders as the last straw.

The presence of their commander in the upper echelons of the military had given them some confidence. Now he was detained.

More than 3 000 ex-Zipra cadres were reported to have deserted the military in the wake of the arrest, an even greater show of support than had been shown after the dismissal of Nkomo from the government in 1982.

That’s a measure of how Dabengwa and Masuku were regarded by the brave men who fought under them during the war.

It is arguable that by generating such resentment among groups of disgruntled men bearing arms of war, the unlawful detention of Dabengwa and Masuku contributed to the conflicts, which the government later claimed to put down, but with extraordinarily brutal force.

The result is what is now known as Gukurahundi. The government had partly created the problem that it was now claiming to solve by using brutal force.

A similar view is that the arrests and re-arrests of Dabengwa and Masuku soon after their acquittal were part of the government’s efforts to build a case against Nkomo and Zapu as enemies of the state and to justify the clampdown and brutality by the notorious 5th Brigade, which fronted the Gukurahundi campaign.

The sustained and bloody campaign needed a narrative suggesting that there was an insurrection which was being directed by subversive elements at the top. Dabengwa and Masuku were easy targets.

Nkomo had already fled Zimbabwe claiming refuge first in Botswana and later in Britain, the former colonial power. His two top commanders were now in jail. Their acquittal had changed and disrupted the narrative. They had to be arrested again, even if shamefully on the same charges.

As the New York Times reported on April 28, 1983, “The rearrest of Mr Dabengwa and his five associates appears to reflect the government’s determination to go on branding Mr Nkomo’s party, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union, as subversive.”

Painting Zapu as subversive gave the world a contrived and exaggerated impression that the Zimbabwean regime was facing an internal security threat. It allowed the regime to perpetrate Gukurahundi without anyone in the international community telling them to stop.

As Zimbabweans now know too well, the narrative of subversion is one that is much favoured by the Zanu PF government, whether under Mugabe or Mnangagwa. It provides justification for the deployment of coercive instruments of the state against the opposition and civil society.

It is hardly surprising that many opposition and civil society activists have at one point or another found themselves facing charges of attempting to subvert a constitutional government.

The unsung heroes of these trials and tribulations were the wives of Dabengwa and Masuku.

It was they who brought cases on behalf of their incarcerated husbands.

One was a legal challenge against government’s refusal to grant their husbands access to their lawyers.

They were successful, but their audacity and success came at a heavy price: the wives were prohibited from visiting Dabengwa and Masuku whilst they were in detention.

Needless to say, Dabengwa and Masuku suffered grievously at the hands of their former comrades.

They were kept in detention for an awfully long time without receiving trial or review.

Their lawyers, including Adrian de Bourbon SC and Bryant Elliott, were brilliant in their representation. Sadly, Dabengwa had to witness the demise of his old comrade Masuku, who succumbed to ill-health in 1986 while in detention.

May your soul be at peace as you now share company with other comrades who departed before your time. Rex, Mafela, Nikita, JZ, Tongogara, Umdala Wethu and many more.

Although they had eventually moved him to hospital, Masuku effectively died at the hands of the State.

Nkomo recounted that the authorities had denied Masuku’s dying wish to see his comrade, Dabengwa who was detained at Chikurubi.

In her brilliant memoir, Through the Darkness, Judith Todd gives a fine account of those truly dark days and the trials and tribulations faced by Dabengwa and Masuku and other ex-Zipra cadres.

Nkomo thought the detention of Dabengwa and Masuku had an impact on the integration of the armies and efforts to keep things calm.

For him, as he recounts in his own memoir, problems arose as “the people best able to keep the remaining dissatisfied elements of Zipra under control were removed from the scene” those people were Dabengwa and Masuku, the commanders who had earned the respect of the fighters.

Without them, there was no more calming influence and disaster followed as conflicts escalated.

It is easy to put all of this upon the shoulders of Mugabe. He was, after all, the leader.

But the fact of the matter is that Mugabe did not act alone. He was head of a system and that system bears responsibility too.

If Mugabe was the conductor, he had an orchestra that he led.

Senior members of the current government have much to atone for with regards to what happened to Dabengwa, Masuku and others.

Mnangagwa was the minister in charge of state security. Nkomo has no kind words in his memoir.

But these men will probably eulogise over Dabengwa’s corpse and pretend nothing ever happened.

They will probably say “let bygones be bygones” as they have said a few times before.

They never publicly apologised to him while he lived. They are unlikely to do so in death. And even if they do, to what end when the man is no more?

We learn from both Nkomo and Dabengwa that all this might have been avoided and history might have taken a different turn had one man they had grown to respect and admire lived: Josiah Tongogara, the iconic commander of Zanla, the military wing of Zanu.

In an interview with CITE, Dabengwa speaks well of Tongogara and casts doubt on the so-called “accident” that claimed Tongogara’s life on the eve of independence.

Apparently, Tongogara had shown himself to be a unifier between the fighting armies and parties and had preferred Nkomo to lead the Patriotic Front.

Dabengwa thought Tongogara’s mistake was to show his hand so openly during the Lancaster House talks in London for in doing so, he had generated enmity in his own camp.

These views are echoed by Nkomo in his autobiography, The Story of My Life: “Josiah Tongogara “… had been the great revelation of the Lancaster House Conference.

“Even the British officials who might have been most prejudiced against a man of his militant background came to admire and like him.

“He was a true patriot, dedicated to the unity of Zimbabwe and impatient of unnecessary divisions… I was confident that, within Zanu, Tongogara would be a powerful voice for unity …”

Ian Smith, a bigger nemesis also shared similar positive impressions of Tongogara in the future of the country.

I qualify this, of course, with contrary thoughts of ZANLA cadres who had different views on Tongogara’s reign as commander.

In this regard Fay Chung’s autobiography is a useful source.

It’s a reminder that history is a series of multiple stories, never a single narrative. But the story of Tongogara is for another day. Today is Dabengwa’s time.

In a twist of history, the man who had allegedly tried to overthrow the government and had been unlawfully detained for it, Dabengwa became a comrade once more after the Unity Accord signed between Zapu and Zanu in 1987.

It was in reality a big political compromise in which Zapu effectively succumbed to the brute force exerted by Zanu.

The onslaught was relentless and the world did nothing to stop the Mugabe regime.

They were the flavour of the times, seen as progressive despite the atrocities.

When Dabengwa was released from the unlawful incarceration he had endured, he found that his party had capitulated to Zanu PF.

Detained, he and fellow detainees had been tools at the hands of Zanu PF, their dire situation forcing Nkomo and ZAPU to give in.

It was a hard for Dabengwa and others who had suffered to walk in and work together with the men who had committed atrocities.

But Nkomo was their commander and as lieutenants they respected and followed his lead.

The reluctant convert became a senior minister in the Zanu PF at one point holding reins at the powerful Ministry of Home Affairs.

This was an ironic turn of events given that it was a Home Affairs minister who had tormented him and his fellow comrades just a few years earlier.

Now he had to play the role of enforcer of draconian laws of the state.

It wasn’t pretty, especially when people rioted over price rises in 1998.

The reaction of the police was excessive. His fellow war veterans had demanded and received huge payouts and before then the war veterans fund had been looted by political elites.

The government that he served paid huge amounts of money to war veterans, which were outside the budget, leading to an unsustainable deficit and impacting the national currency in a hugely negative way.

It was ugly. It must have been deeply uncomfortable for him, using such excessive force against fellow citizens.

He was now part of the same regime that had persecuted and accused him of attempting to overthrow it.

The same regime was accusing another liberation icon, Ndabaningi Sithole, of the same offence that he had faced. He must have wrestled with his conscience. But he was deep inside a hideous system.

It is a chapter of his life which, with the benefit of hindsight while he lived, he would probably have wanted to forget.

But few men have perfect resumes of their lives. At some point in their lives, men and women make mistakes. They falter.

The difference is some keep making them, while others try to make amends. Those who try might succeed but even if they fail, the attempt to make corrections is itself an honourable thing.

Dabengwa spent the sunset years of his life reconnecting with the people and trying to do the right thing.

Critics might argue that his political career suffered a mortal wound in 2000 when the steam-rolling MDC took Bulawayo in the general elections.

Dabengwa was one of the major casualties of that electoral tsunami and he never recovered.

Would he have left voluntarily had he prevailed and remained a key member of the Zanu PF establishment? That will remain moot.

Some of the MDC faithful might not be very forgiving after he backed Simba Makoni, a candidate who some believe helped split the presidential vote or at least gave Mugabe and his allies room to manipulate the result. Still would it have mattered?

There is a view that Tsvangirai won anyway and what stopped his march to power was not Makoni but the military might which simply refused to allow a Mugabe defeat.

In any event, while Dabengwa did not seem to rate Tsvangirai in 2008, over the years, as he took on the role of elder statesman he seemed sufficiently persuaded by the MDC.

In 2018 he openly backed Nelson Chamisa for the presidency. Many respected him for that bold endorsement.

There are few people who in their illustrious lives earned and commanded respect across parties, regions and ethnic lines.

Dabengwa was one of them. He was highly regarded even by people who disagreed with him.

As already pointed out, there are parts of his political career where some may have misgivings but they do not despise Dabengwa for it. They disagree but do so respectfully.

His quiet, soft-spoken and calm character was charming and disarming.

I had first hand encounter with him as a young lawyer in Harare when he was Home Affairs minister.

A certain company had fallen into debt. He was the guarantor to a facility taken by the company.

When I saw his name on the documents, I hesitated and went to speak with my boss.

I did not want to embarrass the firm. I could be accused of being overzealous!

The boss very correctly threw it back into my court and said it was my case, therefore it was my decision on how to proceed. I decided to write the minister a letter of demand.

A few days later my secretary rang to advise me that Dabengwa was on the line for me. I hadn’t expected it so soon.

“Good afternoon, minister,” I said. He must have sensed my hesitation.

“Good afternoon, Mr Magaisa,” he replied. “I’m sorry for the trouble. But can I please make an appointment to come and see you over this matter?”

Now that was awkward. The minister wants to come and see me?

“No problem, Minister. We can make a mutually-convenient arrangement,” I said.

“No, Mr Magaisa, let me come there myself” as soft-spoken as ever.

I wasn’t sure what to expect. Was he trying to intimidate me? He was, after all, a big man and I was just a young lawyer trying to find and define my path.

I waited. Sure enough he came to Beverley Court where our law offices were located. He sat at reception like all other visitors and waited his turn.

When he came to the office he was warm and respectful. We spoke a little, exchanging pleasantries. I offered tea but he politely declined.

Then he took out his chequebook and wrote the amount and signed, apologising profusely for the trouble that his associated business had caused.

“It will never happen again,” he promised as we shook hands and he left. It was a humbling experience.

Here was a man of power, submitting politely to the rule of law. I admired that quality.

The visit had created a bit of a buzz around the office so I had quite a tale to tell to many people.

I remembered a favourite scripture: Give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what is God’s. The man of power had given his dues to Caesar. That is as it ought to be.

That encounter left me with a great impression of the man. I had tried to go out of my way to exercise forbearance, to treat him like a big man.

But he just wanted to be treated like an ordinary businessman who had obligations to fulfil.

He was not asking for favours. He knew he had faltered and there was a duty that needed to be met and he did just that.

This is the type of leader that Zimbabwe has been yearning for.

In many ways, I do sincerely believe that Dabengwa could have made a great president.

He understood the pain and suffering of authoritarian rule — he had opposed it more than once and had suffered under two successive authoritarian regimes.

But he had also served one of the authoritarian regimes and later had sufficient time out in the cold, reflecting upon his life and career.

He had listened to his conscience and complied with its demands.

Even if it was now too late for him to be president, Dabengwa would have been a great guide and adviser.

Perhaps the words of the judge who acquitted him in his treason trial sum up the character of the man.

Quoted by the New York Times, Judge Hilary Squires, who had served as a cabinet minister during the Smith regime said Dabengwa had been “the most impressive witness any of us has seen in court in a long time.’’

For us, he has, indeed, been a most impressive witness and servant of our struggles.

A dignified and courageous man, words alone do not do justice. It was an honour, comrade.

May your soul be at peace as you now share company with other comrades who departed before your time. Rex, Mafela, Nikita, JZ, Tongogara, Umdala Wethu and many more.

The struggle here, for human dignity, fairness, common sense and economic well-being will continue with a new generation.

The torch has been received and it shines brightly, despite the enormous challenges.

The young suckers that must grow in place of the old banana tree that has retired are here, as indeed, the great Chinua Achebe would approve quoting the wisdom of his Igbo forbearers.