ZIMBABWE’S recent droughts have been a brutal reminder that climate change is not a future risk but a present reality.

The 2023–24 season delivered an “intense and widespread drought” that slashed cereal output to roughly 1.3 million tonnes almost 40% below the five-year average and saw maize production collapse to about 635,000 tonnes, over 60% below normal.

Those numbers are not just statistics; they are livelihoods evaporating, hunger creeping back into households that once fed themselves.

Yet, amid the headlines of failed rains and rising food aid requests, a quieter story of resilience is unfolding: agroecology the re-centering of local knowledge, diversified cropping, soil health, water conservation and community seed systems is helping Zimbabwean smallholders weather droughts in ways that purely input-driven models cannot.

This is not romanticism. It is a practical adaptation grounded in evidence and lived experience.

Agroecology reduces vulnerability by changing what farmers rely on. Traditional reliance on monoculture maize, often dependent on purchased seed and fertiliser, exposes households to market shocks and to seasonal rainfall failure.

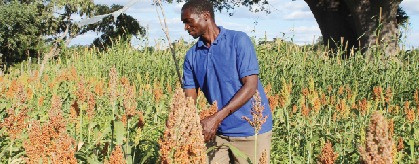

Agroecological practices crop diversification (sorghum, millet, rapoko), intercropping, conservation agriculture, mulching, zai pits, small-scale water harvesting and integrated crop-livestock systems spread risk across species, seasons and micro-environments.

When maize fails, millets and sorghum often persist; when rains are late, mulched soils retain moisture longer.

- Irrigation panacea to droughts: Haritatos

- 60% of Zim has never known electricity

- Hunger stalks Chiredzi villagers

- Hunger stalks Chiredzi villagers

Keep Reading

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has repeatedly highlighted Zimbabwe’s exposure to recurrent droughts and the need to rebalance production systems toward resilience.

Community-driven interventions like Pfumvudza (a conservation agriculture approach promoted by the government and partners) illustrate how modest changes multiply.

Peer-reviewed research on Pfumvudza and similar smallholder packages found improved yields and greater resistance to drought stress in participating communities, because the approach concentrates inputs on small, well-managed plots, combines soil and water conservation techniques, and mobilizes collective learning.

That translates into higher chances of a family having some grain at the end of the season rather than none.

Agroecology is low-cost and scalable for resource-poor farmers.

Technical solutions deployed by FAO and partners in Zimbabwe emphasize local seed systems, which reduce dependence on costly hybrid seed and preserve drought-tolerant landraces.

FAO programming in the country has supported communities to adopt agroecological practices as part of resilience-building efforts, combining short-term humanitarian response with longer-term adaptation.

This dual focus is crucial: it helps households survive the lean months while progressively strengthening their systems for future shocks.

One of the clearest benefits of agroecology is speed and agency. While large irrigation schemes and expensive mechanization projects take time and capital, farmers can implement techniques like zai pits, mulching and crop rotations immediately, using local labour and materials.

When the 2023/24 El Niño-driven drought battered broader cereal production, areas where smallholders had adopted conservation techniques or diversified cropping regimes generally fared better than pure maize monoculture plots.

The media and reporting around Zimbabwe’s agricultural rebound in later seasons also attribute part of the recovery to up-scaled smallholder schemes and to the promotion of drought-tolerant crops.

We must, however, be honest about limits and trade-offs.

Agroecology is not a silver bullet that will instantly reverse macroeconomic constraints, market failures, or years of under-investment in rural infrastructure. It does not, on its own, create storage, processing capacity, or fair markets.

Nor does it absolve governments and donors of the duty to invest in irrigation, research into improved drought-tolerant varieties, and social protection for the most vulnerable.

Instead, agroecology should be framed as a foundational strategy: one that builds soil, knowledge and social capital so communities are not starting from zero when the next shock hits.

Policymakers must therefore stop treating agroecology as a fringe alternative and start integrating it into mainstream agricultural planning.

That means aligning extension services to teach low-cost water-saving practices, funding community seed banks, supporting farmer-to-farmer knowledge exchange, and protecting communal grazing and wetland areas that act as climate buffers.

It also means reorienting subsidies and public procurement to reward resilience buying sorghum and millet for school feeding programmes, for example, would create demand for drought-tolerant staples and stabilise prices for smallholders.

Donors and international institutions also have a role: they should pair immediate humanitarian support with investments that seed longer-term agroecological transitions.

FAO’s country briefs and resilience programming have already pointed this way, emphasizing the need to combine emergency measures with interventions that restore soil moisture, diversify production and rebuild livestock assets. Those are precisely the levers that agroecology operates on.

Zimbabwe’s farmers are active agents, not passive victims.

When supported with training, seed, and market linkages, they innovate — reviving traditional grains, experimenting with contour ridges, and rethinking cropping calendars.

These adaptations, if scaled thoughtfully and accompanied by public investment, can blunt the worst effects of future drought spells and reduce the bleak reliance on food aid that plagued the 2024 season.

Agro-ecology is not a nostalgic throwback to a romantic past it is a pragmatic, evidence-backed pathway to resilience.

For Zimbabwe, where droughts are becoming more frequent and severe, supporting agroecological transitions is both a humanitarian imperative and a strategic investment in food sovereignty.

The choice facing policy-makers is clear: double down on single-crop vulnerability, or invest in diversified, locally grounded systems that shield families when the skies fail.

The lives and futures of millions depend on choosing the latter.