Thriving swathes of lush vegetation, overlook an underlying vein of pure water at a picture-perfect vlei surrounded by Gabheni and Inqama villages in Matobo, Matabeleland South province

On a windy June morning, a visiting group of legislators and environmentalists on a fact-finding tour in the build up to COP15 on wetlands is bedazzled by the scenery in the remote region and is constantly bombarding a local researcher and tour guide named Tafadzwa Tichagwa with questions.

“The water coming out here flows into the next wetland where it meets more water then flows into the Mtshabezi river and eventually Mtshabezi Dam, which is one of Bulawayo’s major water sources,” explains Tichagwa while pointing at a pool steadily forming from the edges of a granite rock.

Seemingly oozing from a divine vessel — a rock — the life-saving liquid is an instant appeal to the eye and whispers “purity”.

“But, I would advise against drinking it because we have had recent cases of cattle sinking and dying on this channel as they seek water during dry seasons, also it could be contaminated by chemicals from local farming activities,” says Tichagwa as the delegation proceeds its mission.

Although his advice gets endorsement from the province’s representative for the Environmental Management Agency (EMA), something unimaginable happens. An academic crouches, scoops two palmfuls of water and sips away.

“What we have to value about nature is that it is interpretive, (so) one should be able to understand how to make use of the environment on the basis of observing it,” environmental researcher and conservation expert Solomon Mungure told this publication.

His actions, perhaps viewed as too basic for an academic, made a case for age-old African science and its potency as a tool for understanding ecology and the interconnectedness of natural life.

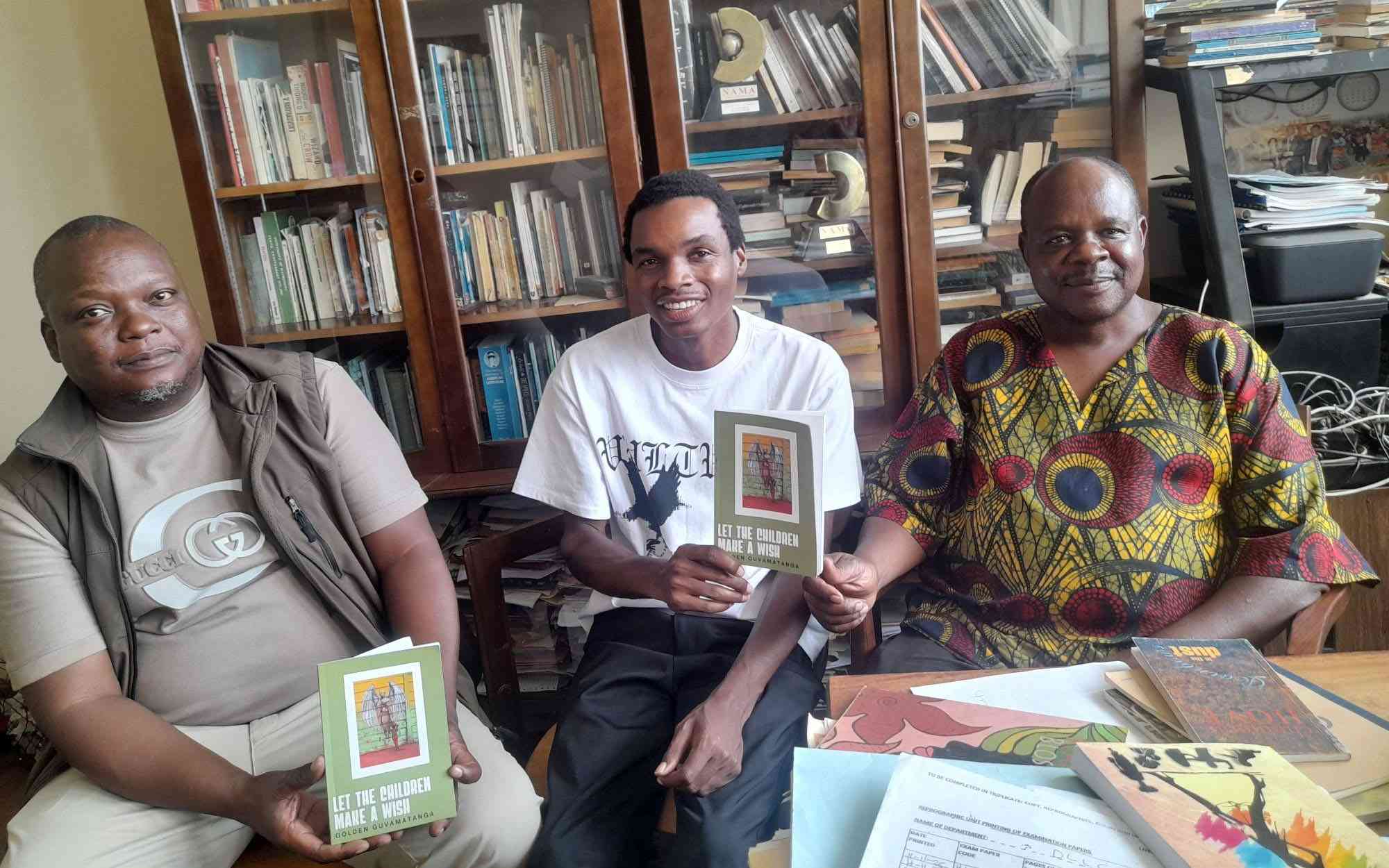

- Byo author eyes SA award

- WB revises downwards Zim growth

- Letters: Zanu PF to blame for anything wrong in Zim

- Shortages show the poverty of ideas in govt

Keep Reading

Mungure insists that a mixture of healthy looking vegetation and buzzing aqua life are to a high degree evidence of the water source’s purity because had it not been the case, the living organisms would be dead.

“The Zimbabwean challenge is that if one is said to be a professor of ecology, they start by doing a lab test, that is the higher end of knowledge but that is not where we live.

“In the past, our communities used to apply local wisdom on the environment effectively because they understood it,” he says.

At Chinhoyi University of Technology research on observing micro invertebrates and diatoms —organisms found in water — to establish water quality is ongoing. The study is key in “incorporating local science” and ensuring a multi-sectoral approach to local wetland preservation, says CUT senior lecturer Tongayi Mwedzi.

“We are looking at organisms from diatoms, what is commonly known as mazerere in the Shona language.

“We are trying to establish what kind of information mazerere that we see in the water can give us about its quality as well as the state of our wetlands,” Mwedzi said in a recent public presentation.

However, despite apparent accuracy in displaying the health of nature, African science has been largely relegated to the peripheries of the country’s wetland management strategies and dire consequences have emerged.

In December last year, four rhinos died at a Lake Chivero Recreational Park owing to water contamination caused by cyanobacteria, a toxic bacteria found in polluted water.

The contamination, which also claimed thousands of fish, three zebras, four wildebeests, fish eagles, and livestock from nearby farms, confirmed massive pollution at one of the country’s major wetlands — a Ramsar-protected site. Prior to the wildlife disaster, an ignored foul sewer stench and dark green shade of water had long communicated impending danger.

“Funds must be channeled towards research and revival of indigenous knowledge systems. I feel home grown knowledge bodies can be more sustainable than alien ones (because) borrowed philosophies can hardly suit our communities,” says Chipinge-based environmental and culture researcher Phillip Kusasa.

Historical findings reveal that ancient environmental beliefs hinged on mysterious myths and taboos have for long worked as effective homegrown conservation mechanisms.

Indigenous knowledge systems, Kusasa says, provide robust insights into the sustainable management of wetlands, often encompassing traditional practices, beliefs, and resource management techniques passed down through generations.

He adds that local wisdom provides an intersectional approach to wetland conservation, integrating ecological knowledge with social and cultural dimensions.

“I think the way that traditions preserve these sites is very powerful because it is more about faith and belief than modern science.We believe in the existence of spirits in our nature so we regulate our conduct and that ensures sustainability on our natural sites,” Kusasa said.

As Zimbabwe host over 172 countries at the ongoing Ramsar Convention on Wetlands COP15, in Victoria Falls, there have been growing calls to revisit and revive indigenous wisdom to ensure sustainable management of wetlands.

In 2021, a national mapping survey —the latest, found only 17,63% of recorded wetlands in pristine condition, with over half moderately degraded and 26,72% severely damaged.

In Matobo, similar to many places across the country, as stakeholders question veracity of wisdom that has not gone through laboratories, African science is fading and consequently human encroachment threatens to destabilize biodiversity. For Mungure, a renaissance of local knowledge hybridized with lab science is urgent in the country's ecological conservation framework.

“Society is going back because it did not add value on local knowledge…we adulterated our own systems,” says Mungure, who through an unpredictable act had conducted a masterclass on how respect and application of ancient environmental knowledge could save millions of dollars used by local authorities towards water purification.