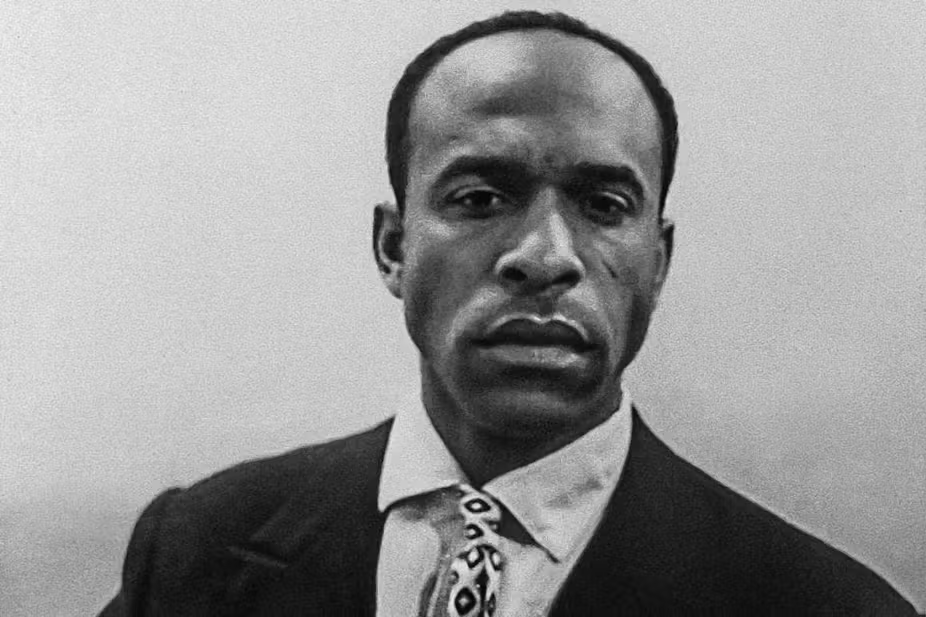

As the world commemorates 100 years since the birth of Frantz Fanon, we are compelled not only to revisit his blistering prose and revolutionary ideals, but to confront the internal terrain he so fiercely mapped the psychic scars of colonisation and the painful, beautiful process of becoming.

For artists across Africa, and particularly in Zimbabwe’s burgeoning creative sector, Fanon is more than a theorist of liberation he is a whisper in the studio, a scream on stage, and a compass for navigating the labyrinth of identity, memory, and imagination.

“The colonised is elevated above his jungle status in proportion to his adoption of the mother country's cultural standards.” Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

Fanon’s work dissects the colonized mind, revealing a fractured self one caught between imitation and erasure.

For the African artist, this tension is not just philosophical; it’s deeply visceral. It answer these rhetorics which in this article I articulate.

Firstly, how does one compose a song in a language that once silenced your ancestors?

This question doesn’t just interrogate linguistics it interrogates pain. It asks how the very medium once used to suppress identity can now be used to resurrect it.

The creative walks directly into this fire. In poetry, they often use English, the coloniser’s tongue not as surrender, but as strategy.

- Independence: Dream deferred or betrayed?

- Heroic sacrifices and the evolving generational mandates

- Edutainment mix: Unmasking the self: Frantz Fanon’s revolutionary psyche and the awakening of the African artist

Keep Reading

The creative takes the language and refashions it into a vessel of protest, rhythm, memory, and vision. English, French or Portuguese becomes a scalpel to cut open colonial wounds and a thread to stitch new meaning.

The creative responds not with brushes but with voice, sound, and breath. Music becomes layered with Shona, Ndebele, or other indigenous languages that reclaim the body and the spirit.

Where poetry in English questions and provokes, music in African languages heals and remembers.

Through rhythm and tone, the creative paints bodies not as sites of shame but as temples of resilience. Art becomes both mirror and shield, reflecting pain and guarding pride.

To speak from the soul when the soul has been coded foreign is to engage in a deliberate act of reclamation.

It requires the creative to first confront the reality that colonisation, cultural imperialism, and systemic oppression have labeled their inner world their voice, traditions, and truths as invalid, exotic, or inferior.

This coding of the soul as "foreign" is not just about language or expression; it's about identity, memory, and spiritual dislocation.

Frantz Fanon, in Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth, described this condition as one where the colonised internalize the values of the oppressor, creating a psychological fracture.

The result is a creative silence a soul muted by imposed shame, misrepresentation, and erasure.

But speaking from this soul is possible and necessary.

It begins with unlearning colonial conditioning and reaffirming indigenous knowledge systems. The African creative achieves this by grounding themselves in ancestral memory, community narratives, and lived realities.

Even when using languages and forms introduced by colonialism, the content the soul is undeniably rooted in African worldviews.

For example, a poet may write in English, but the rhythm, symbolism, and imagery are distinctly shaped by oral traditions, praise poetry, or spiritual idioms.

A dancer may perform on a modern stage but channel ritual movement and communal purpose. A designer may use global fabrics but drape them in ways that honour indigenous aesthetics.

Thus, to speak from the soul under these conditions is not to reject the global it is to re-Africanise expression, to assert that the soul was never foreign, only reframed. It is an act of survival, defiance, and cultural sovereignty.

Fanon helps the creative understand that their soul is not broken it is buried beneath centuries of imposed falseness. Their work, then, is the excavation and revoicing of that soul, not for validation by external systems, but for the healing and awakening of the self and community.

Fanon was a psychiatrist by training and a revolutionary by calling. His understanding of colonization wasn’t just about land it was about the mind.

In The Wretched of the Earth (1961), he wrote of art as a therapeutic act, where the colonized can retrieve a fragmented identity through creativity.

“The colonised subject is always presumed guilty. The native is declared insensible to ethics; he represents not only the absence of values but also the negation of values.”

The Wretched of the Earth

This is precisely where Zimbabwean artists scarred by colonial history, economic crises, and cultural dislocation — find resonance. Art becomes a recovery of memory, a return to rhythm, a reimagining of the self. In Fanonian terms, this is not nostalgia; it is resistance.

Fanon’s vision was revolutionary, not just in politics, but in aesthetics. He challenges the artist to move beyond mimicry, to reject the flattering of foreign tastes, and to dive into the psychic soil of their own people.

His work calls on creatives to abandon the role of cultural intermediaries and become architects of new, self-defined realities.

This philosophy is embodied today across various artistic disciplines. In poetry and spoken word, artists excavate silenced histories, confront social injustice, and reframe identity using both ancestral and contemporary tongues.

In music, traditional instruments like the mbira, ngoma, or hosho are fused with modern sounds such as Afro-punk, electronic, and jazz, creating sonic landscapes that are both futuristic and deeply rooted.

Theatre and performance revive ritual through movement and narrative that resist colonial dramaturgy and instead centre communal memory and healing. In fashion, textiles, body art, and indigenous motifs are reimagined not as exotic backdrops, but as living archives of resistance and beauty.

Visual artists move beyond colonial realism toward abstract and symbolic forms that engage with African cosmologies and lived realities. Meanwhile, film and digital storytelling portray the post-colonial condition not merely as trauma, but as unresolved prophecy and generational reckoning.

These are the modern griots and Fanonian creators—voices that refuse to be interpreters for a Western gaze and instead speak from within. Their practice is not just art. It is insurgency. It is healing. It is a reclaiming of self and society.

As we reflect on a century since Fanon's birth, let us resist the urge to reduce him to a symbol or slogan. Fanon was urgent, radical, and deeply necessary.

His writings were not passive reflections but active instruments of liberation blueprints for inner and collective revolution.

For the African creative today, his voice still calls: to disrupt, to heal, to reclaim.

Across Zimbabwe and the continent, artists are not merely makers of culture they are memory keepers and spiritual surgeons, confronting the weight of history with every lyric, movement, image, and material.

In their refusal to forget or conform, they embody Fanon’s enduring challenge. His heartbeat echoes in the art that dares to disturb the colonial wound and declare:

“We are not what you made us. We are what we reclaim.”

nRaymond Millagre Langa is a Zimbabwean poet, independent researcher, musician, and activist whose work fuses ancestral memory with contemporary social commentary. He is also the founder of Indebo Edutainment Trust, an arts-based organisation that uses creative expression to challenge colonial legacies, promote cultural identity, and empower communities through education and performance.