It is well and good to love the Caine Prize but here I choose to take a road less travelled.

Bookworm

Now don’t get me wrong, I have nothing against the Caine Prize. I have met many of the winners, but I cannot help but think about the Caine Prize’s growing influence in shaping contemporary African literature.

Should it’s influence not be questioned?

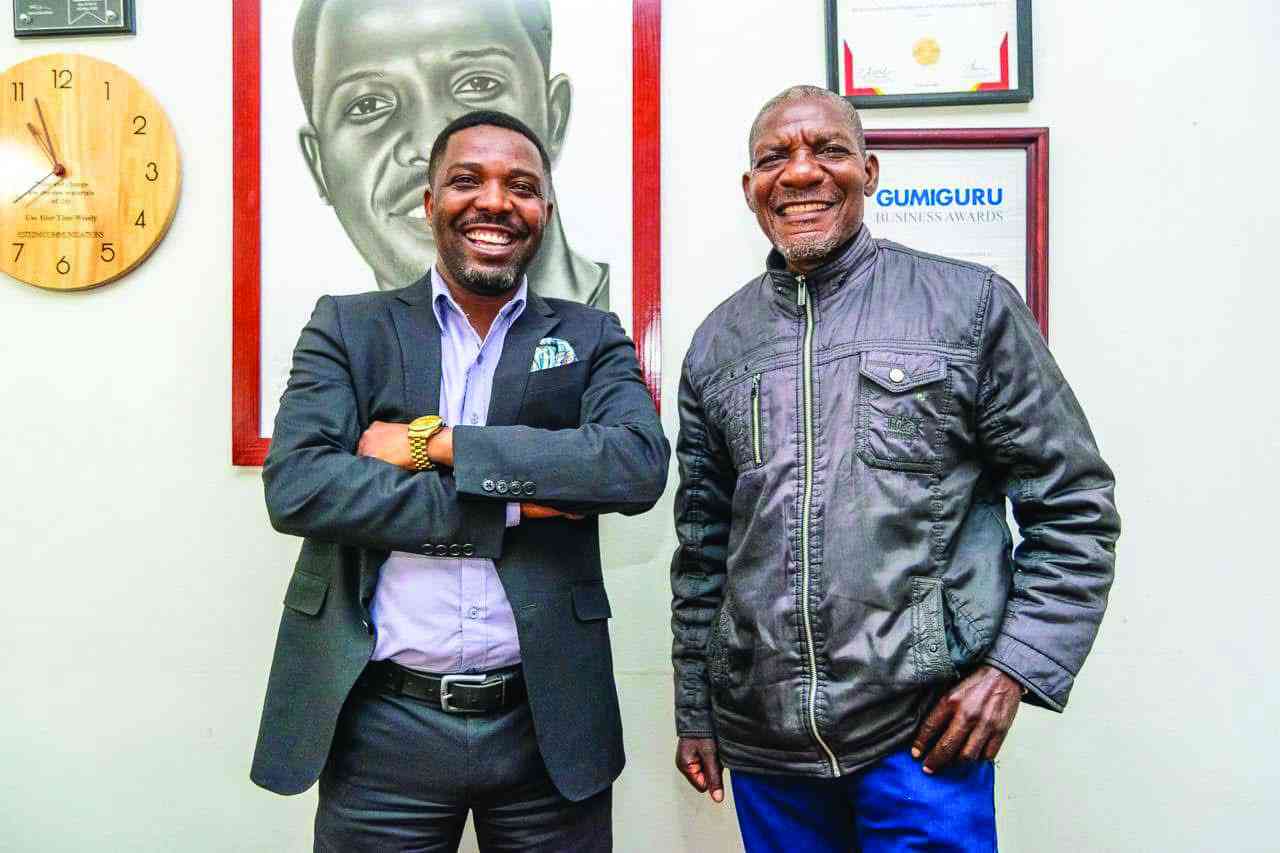

In 1979, Dambudzo Marechera’s reaction as joint winner of the Guardian Fiction Award ceremony has become legendary.

While fellow writers such as Angela Carter and Doris Lessing were praising Marechera as the new star of African literature, the prize-winner used the occasion to protest against the hypocrisy of the literary establishment.

At this specific occasion, Marechera complained that an African writer was expected to write only about Africa and advocated for the removal of such prefixes as “African” or “Irish” from the substantive term “writer”. He spoke of himself as collecting awards in London while his people were being killed in Zimbabwe. The irony of this comment is also the truth of it.

The House of Hunger was certainly the kind of book for the London crowd in attendance and expected from an African writer — it’s a gut-wrenching story, dripping with blood and poverty and violence — a book that confirms all the negative characteristics of the Africa of their imagination.

- Mthuli evades Parliament grilling

Keep Reading

Yet, The House of Hunger, for instance, reveals a history of universal decomposition, the sinister spiral of decay and deterioration reminiscent of TS Eliot’s The Waste Lands.

Marechera saw through this.

He could see how he was being patronised and used as the eccentric poster-boy of African literature. He knew he was being branded as merely a product for the “African Writers Series [AWS] public.” He played to the gallery when it profited him but most importantly, he knew when it was time to run.

In fact, Marechera’s relationship with the literary establishment in London questions and challenges our perceptions and definitions of African literature, especially the relationship between its authors and producers.

For instance, Heinemann meant well by starting the African Writers Series as they were certainly trying to encourage non-African readers to experience rich stories of Africa.

The problem lies in the fact that African literature as we know it continues to be produced “more as a commodity than as a value,” as Tinashe Mushakavanhu puts it. The primary market for the AWS or the Caine Prize is not Africa itself, but “the rest of the world — Europe and North America mainly.”

‘Judges bring preconceived ideas on African stories to the table’

The Caine Prize divides opinion. Is the Caine Prize a carrot being dangled for naïve and unsuspecting African writers? And that it is called a Caine Prize “for African Writing” is in itself interesting.

I am yet to see an international prize “for European writing” or “for American writing.” The label — African writer — largely reflects on the consumers of “African” or “post-colonial” literatures.

In most cases, the producers and the market of “African literature” have already placed a value judgement on the work even before they have read the stories.

Such questionable categorisations are to be expected in a world where the production (editorial, publishing) and consumption (marketing) of “canonised” African literature is largely in the hands of “outside” experts.

What is known globally as African literature lies outside the hands of its creators and subjects, but is in the tight grip of institutions that obviously possess fixed ideas about what African literature should and should not be, and what authentic African characters can or cannot do.

There is a lot of issue fatigue in African Literature and the Caine Prize is doing nothing but to old age stereotype Africa as being a message continent.

Historically, African writers are known for the message in their fiction or poetry.

This is a colonial mentality that is embedded in how we — Africa — produce our literature.

African literature has always been reactionary and African writers have always been writing against. It’s time our literature confronts the tired horrors we endure every day in new and refreshing ways.

It is also high time African Literature embrace high concepts such as sci-fi, magic realism, etc — concepts that make the African story engaging and captive.

Many young African writers have been running to win the Caine Prize because it comes with a lot of celebrity clout. I have met young writers whose only ambition is to win the Caine Prize.

Nothing else matters to them. I think it is because the Caine Prize has sold itself as such — the torch bearer of contemporary African writing.

If the Caine Prize is a sincere Pan-African project then it needs to relocate its headquarters to Africa, wherever that is.

This white fetishising of African writers and African literature just has to stop.

While the award’s ethos may be predicated on good intentions, there is more than what meets the eye. Let’s not be lured by writing workshops at tourist resort places. Young African writers must learn from the lesson of Marechera. Take advantage of those whose mission is to take advantage of you and when it’s time to run, don’t hesitate.