In the groove with Fred Zindi

Ido not describe myself as an ardent Bible reader, but on this day I remembered a verse from the Bible which I learned during my secondary school days. 1 Corinthians, Chapter 15:26, reads: “The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death.” I mused, “How can we destroy death and bring back Oliver ‘Tuku’ Mtukudzi?”

They buried the 66-year-old superstar, at his Madziwa rural homestead last Sunday, four days after his death.

Tuku had the most extraordinary funeral service ever held for a popular musician.

I drove to Madziwa with Sam Mataure (Tuku’s former manager and drummer), Watson Chidzomba (Tuku’s manager at Pakare Paye Arts Centre) and South African saxophonist and music producer Steve Dyer, who had come all the way from Johannesburg to attend Tuku’s burial.

When we arrived in Madziwa, the place was already packed as thousands of Tuku fans had been bussed to the venue the previous night. It was crowded.

We parked about 5km away from Tuku’s Madziwa village due to congestion and walked the rest of the way. On arrival at Tuku’s homestead, we were ushered to the VIP tent where I was made to sit next to Steve Makoni (Tuku’s very close friend and musician) and Member of Parliament for Uzumba, Simbaneuta Mudarikwa. We greeted each other. Mudarikwa then said to me, “Nematambudziko” (Condolences). Unable to think of anything more profound or perceptive to say, I responded with: “It is indeed a sad day.”

This funeral greeting continued for a while with all those nearby, some familiar and others not so familiar. We paid our respects by shaking hands. Many of those who greeted me claimed to have been friends with Tuku. “Sure, I knew him. If you look at my Facebook page, I even posted a photo I took with him,” most of them would say.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Under the eyes of cameras and reporters from local and international media the assembly of an estimated 6 000-strong congregation became noticeable although it was difficult to know who was who there. The photographers were anxious to focus on Daisy Mtukudzi, Tuku’s widow, and they swiftly surrounded her as she took her place. Some of Tuku’s children were also present including Sandra and Selmor (born to a different mother, Melody Murape).

Inside the courtyard and out in the street, the powerful sound of the public address system blasted out Tuku’s music and speeches from dignitaries , family and friends among them Oppah Muchinguri-Kashiri, Sandra Mtukudzi and Alick Macheso.

Tuku had been declared a national hero. It was therefore logical to involve government in the proceedings. Close to a hundred members of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces were involved in the cooking of meals which were provided to the 6 000 plus people gathered here. Tuku had declared before his death that he did not want to be buried at the National Heroes’ Acre. Chidzomba, his manager at Pakare Paye, can confirm that this was his daily gripe. His complaint was that the government did not care about musicians. This feeling is said to have been triggered by the way Comrade Chinx was treated after his death in June 2017. Tuku is said to have argued that Cde Chinx was one of them. He handled a gun, just like them. He dodged bullets from the enemy just like some of them and he also sang revolutionary songs throughout his life. Why then was he not buried at the National Heroes Acre? This is where the government’s attitude towards musicians was seen as negative.

Indeed, the thinking is that there is a different world out there as most politicians are not connected to ordinary people, let alone musicians. One commentator, after hearing President Emmerson Munangagwa’s announcement at Tuku’s residence in Nhowe that people should eat and drink as much as they liked because the government would pay, had this to say, “The government only wants to get credit for things they really don’t care about. They are all jumping on the bandwagon of Tuku’s popularity when they could have helped him in his lifetime. Why was he not flown to Singapore or nearby South Africa for treatment given the nature of our poor hospitals with no drugs? They are all ignorant about the power of the arts!”

This is evidenced by a comment made by one minister who attended Tuku’s church service at Pakare Paye on the Saturday before his burial. He remarked, “I didn’t know that Pakare Paye was such a big infrastructure, and to imagine that this was built by an ordinary musician?”

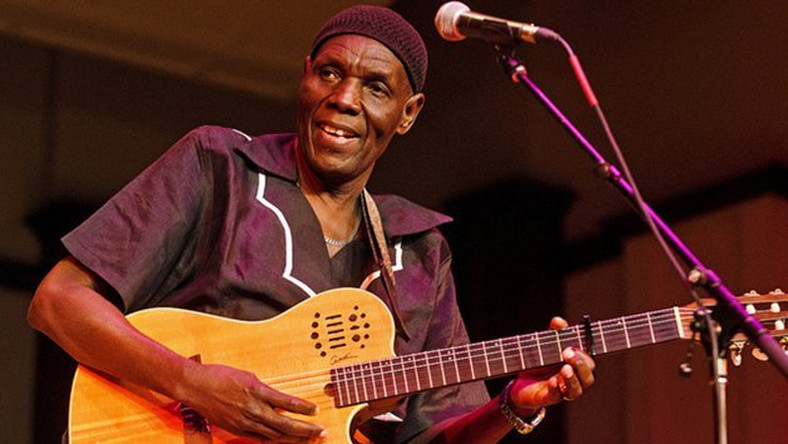

Well, Tuku was no ordinary musician. Many people saw him as extraordinary and as a friend of the oppressed. This message came out of the songs he composed over the years which made up the 66 albums he is credited with.

Another minister mentioned only after his death that Tuku built classroom blocks at his village in Dande. Why was this not commissioned and publicised during his lifetime? It is a question of attitude again. Surely, if his achievements were made known to people during his lifetime, Tuku would have died a better person.

However, if Tuku had chosen to be buried at the National Heroes’ Acre, there would have been chaos as evidenced by the congestion created by the 65 000 people who turned up at the National Sports Stadium for his send-off concert on the Saturday before his burial. The authorities would have had to close off Bulawayo Road.

At the send-off concert, Tuku’s death made it possible for the public to attend a concert, which one would normally pay $20, for free. All the artistes were dying to perform in honour of Tuku’s legacy. Baba Mechanic Manyeruke, Baba Charamba, Baba Harare, Seh Calaz, Soul Jah Love, Enzo Ishall,, Leonard Zhakata, Jah Prayzah, Jah Signal, Alick Macheso, Picky Kasamba and The Black Spirits Band, Guspy Warrior, Pah Chihera, Kinnah, Mathias Mhere and many more, gave their services for free. Others such as Hosiah Chipanga were disappointed that they did not get a chance to perform. Edith We Utonga complained on behalf of the women that there was gender bias in the selection of performers as hardly any woman was given the opportunity to perform. Tuku, in his lifetime, did not discriminate on the basis of gender. He did many collaborations with female artistes such as Fungisai Zvakavapano-Mashavave, Tariro neGitare, Joss Stone, Bonnie Deuchle, Berita, Judith Sephuma and many more.

Winky D, the Kasong ke Jecha hitmaker, was prevented from entering the stadium so could not perform. Security personnel said that they had been given instructions to stop him.

The hearse carrying Tuku’s body entered the National Sports Stadium around 2pm. There were whistles and ululations. Almost everyone was in tears. Often, national heroes are carried by Doves Funeral Services, but hero Tuku’s body was processed by Nyaradzo Funeral Services with company owner, Phillip Mataranyika, driving the hearse.

Both Doves and Nyaradzo were also at Tuku’s village in Madziwa. Apart from five state-of-the-art hearses, Nyaradzo also supplied seven 60- seater buses, four courtesy cars and nine delivery trucks to service the funeral.

Tuku is credited with popularising Zimbabwean music around the world and he served as a symbol of Zimbabwean culture and identity. During my stint in the United Kingdom, every Zimbabwean I visited had at least two Tuku albums, thus showing not only his popularity, but also as a way of expressing their Zimbabwean cultural identity.

Tuku was an experience which left an indelible imprint with each encounter. Such a man cannot be erased from anybody’s mind. He had a song for everyone. I am sure there are still many albums that are going to come out after his death as I am reliably informed that his computer is full of new songs which need to be assembled. (Mono Mukundu and Munya Matarutse, where are you?)

Death has robbed Zimbabwe of its most renowned and internationally recognised cultural icon. He will remain part of the collective consciousness of Zimbabwe for many years to come.

Rest in peace, Tuku.

Feedback: [email protected]