In the groove with Fred Zindi

In 1989, after the CSA Records’ overseas release of The Essential John Chibadura, Mike Ralph, the executive director of Records and Tape Promotions (RTP Records), gave me two gallons of petrol and asked me if I could go to Chitungwiza and persuade Chibadura to leave recording with Zimbabwe Music Corporation (ZMC) and join RTP at a higher percentage rate than what he was getting at ZMC.

The next day, I arrived at 29 Chisvo Road early in the morning in order to catch Chibadura and give him the “good” news.

I told him that Ralph was offering him 25% in royalties as opposed to the 15% he was getting from ZMC. I thought he would, without question accept this higher percentage. Chibadura’s response was: “Tell Mike Ralph and his RTP team to go to hell.” On asking him why, he said that he had received a figure of $19 000 from ZMC and Oliver Mtukudzi had only got $10 000. He was the highest earner at ZMC. I told him that this was because he had been selling more records than Mtukudzi during that period. “Imagine if you were on 25% instead of the 15%, you would have got even more,” I said. He either did not understand this or he was just being naive. From my analysis, he obviously thought that he was getting a salary from ZMC and that his salary was higher than that of Mtukudzi. I tried to explain to him that this trend of him getting higher than Mtukudzi would not go on forever, but he failed to digest this.

In the end, I told Chibadura that he probably needed a manager to deal with his financial affairs, while he concentrated on the music. Here was his response: “Mr Zindi, are you telling me that if I hire a manager, he will have to share with us the money we make as a band? No ways! When we do live shows, sometimes we make $6 000 in one night and there are six of us. So, each one goes home with $1 000. Now imagine if there was a seventh person who calls himself a manager, we would all end up with less than a $1 000 each. So, what is the point of having a manager if he is just coming to take what we have earned?” I tried to explain to him the advantages of having a manager, but he wouldn’t buy it.

Managers have specific roles to play in order to achieve the success of their artistes. I explained to him some of those roles:

The manager would handle the business side of an artiste’s career such as bookings, gigs, live shows, and negotiating royalty settlements with record companies and publishers.

He or she would also look after the administration side of things as well as looking after the band and liaise with lawyers, deal with accounts and give press statements to journalists. He/she will guide the artistes’ career in the right direction.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

The idea behind appointment of any manager is to employ someone who will further advance the artiste’s career. I told Chibadura that if the band was making $6 000 a night, the manager would see to it that the amount was boosted to $10 000 through extra effort which Chibadura did not have time for.

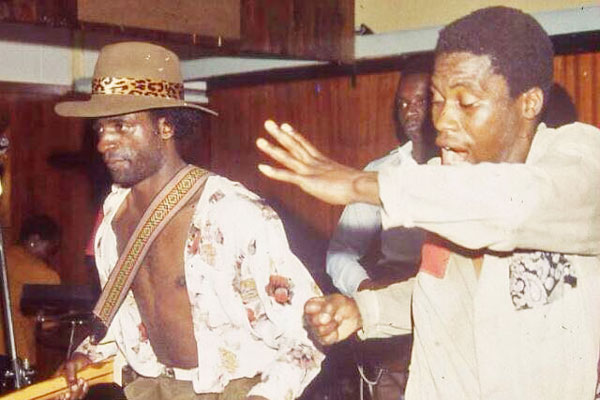

He wanted complete control over his six-piece band, The Tembo Brothers, which at the time was made up of Charles on bass, Bata Sintirawo on rhythm guitar, Innocent Makoni (backing vocals), Douglas Katsvairo, a dancer and backing vocalist, Roderick Chemudhara on keyboards and Chibadura himself on lead guitar and vocals.

One other reason he wanted control of the band’s finances was due to the fact that Chibadura and Tymon Mabaleka of ZMC were said to have hatched a plan where out of the royalties received, the two of them would take a portion first and share between them before the rest was distributed to the band. For instance, if the band earned $10 000 in royalties which were paid out every quarter, Mabaleka and Chibadura would subtract $4 000 and get $2 000 each before declaring to the rest of the band that they had received $6 000, which would in turn be shared by the six members. Chibadura would then end up with $3 000, but gave the impression that his share was equal to everybody’s. Now if he had hired a manager to deal with his finances, this would have been exposed. However, the story became known by everybody because Letty, who was the ZMC secretary and typist at the time, told everyone what was going on. Mabaleka would ask her to type out a ZMC royalty form receipt of $6 000 instead of $10 000, which would be photocopied to everyone, making the transaction look transparent and official. She told everyone about this scam because she was disgruntled over not getting anything out of the deal.

John Enock Nyamukokoko “Chibadura” was born in 1957 in Guruve, Mashonaland Central province. His father and mother were itinerant farm labourers from Mozambique. In 1962, at the tender age of five, Chibadura lost his mother and his father got re-married to a woman who was tough on him. Because he had a hard time with his stepmother, Chibadura was eventually forced to go to Centenary to live on a farm with his grandfather who was a talented mbira player. Unfortunately, his grandfather died three years later. From then on, Chibadura continued to live a nomadic life where he was passed from one relative to another.

In 1968, while in Centenary on a farm, Chibadura started to learn playing the banjo. The following year, there was a serious drought in Zimbabwe, and Chibadura, in search of further education and survival, walked from Centenary to Darwendale where he settled at a farm called Wagon Wheels. He worked at the farm as a tractor driver and lorry driver while attending school. He quit school after Form 3. It took Chibadura another 10 years before he made the move that was designed to realise the dream of becoming the cherished musician he became.

Chibadura launched his musical career in Harare together with Shepherd Chinyani, who became part of a band known as The Holy Brothers. The band was, however, shortlived and some of the band members were reported to have abandoned their musical careers. Chibadura and Chinyani teamed up with Tineyi Chikupo, who was the front man for a band called Mother Band, which he had formed in the early 1980s. Chikupo, however, left his band and Chibadura together with Chinyani teamed with Ronnie Gatakata and Sintirawo and they started performing at a hotel in Mutoko after which they relocated to Domboshawa. In Domboshawa, they signed a contract which enabled them to perform at Mverechena Hotel and the band was subsequently named The Mverechena Band. After being offered a contract to perform at Mushandirapamwe Hotel in Highfield, the Mverechena Band left Domboshawa for Harare and they assumed a new name, The Sungura Boys, whose members included Simon and Naison Chimbetu. The band released albums such as Sara Ugarike and Rugare Tangenhamo which all sold more than 100 000 copies.

Chibadura then moved to Chitungwiza where he was soon to become popularly known as “Mr Chitungwiza”, after the name of the town. Through his music, Chibadura soon became a household name. However, soon after the independence of Zimbabwe in 1980, Chibadura formed his own group known as The Tembo Brothers. With this group, he churned out some memorable albums such as Vengai Zvenyu, Hupenyu Hwandinetsa, Sango Rinopa Waneta, Pitikoti Government, Ndirimuhondo, Mune Majerasi, Mutumwa, Madiro, Kugarika Tange Nhamo, 5000 Dollars Kuroora, Kurera, Zuva Guru, Mudzimu Wangu, Munhu Haana Chakanaka, Mudiwa Wangu Jeneti, Dzidzisai Vana and many more over the years.

Chibadura, with help from JJ Promotions, toured the United Kingdom and the Netherlands in the early 1990s and later Northern Ireland. He also toured Mozambique where he was so popular that he only played in stadiums where his audiences, at some point, exceeded 40 000. In Mozambique, he was often met by the then president, Joaquim Alberto Chissano. Though most of his life was spent in Zimbabwe, Mozambique regarded him as a long-lost son and when in the country, he would be ferried to concerts in the presidential helicopter.

Sometime in 1997, Chibadura was beginning to show signs of failing health. He stopped giving performances, but spent the whole year seeking medical treatment. Out of desperation, he decided to sell his musical equipment and eventually his house in order to meet the costs of medication.

On August 4, 1999, Chibadura succumbed to illness and died. He was aged 42. Although his career blossomed, he never wanted anyone to manage his affairs and had no control on how he spent his finances. Unfortunately, he died a pauper as a result. He left behind his wife and six children who all moved to Domboshawa.

Feedback: [email protected]