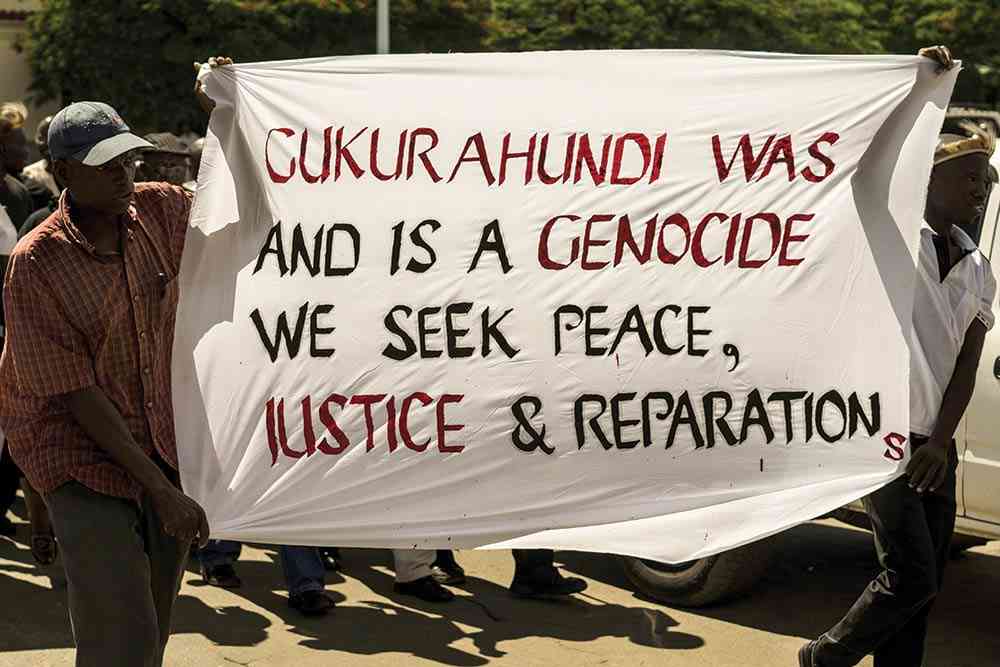

The Gukurahundi genocide, a Zimbabwean state-led paroxysm of systemic torture and killing of more than 20 000 ethnic minority citizens and political opponents in the greater Matabeleland region during the 1980s, ended formally in 1987.

While this brought some respite to the many Matabele people, who were facing an apocalypse at a time when they should have been celebrating independence like other regions, the wound is still festering after nearly four decadesof the Gukurahundi aftermath.

The perpetrator state, which has arrogated to itself the role of judge and jury, has been obstructing progress towards lasting truth, justice and reconciliation by either blocking independent initiatives or by embarking on half-heartedinitiatives that give a semblance of genuineness.

One aspect of the genocide that has been absent in discussions about Gukurahundi is reckoning with the effects of the genocide on health and wellbeing.

Sadly, the grim effectsof the genocide on health and well-being have been glossed over and peripheralized.

People havebeen rightfully focusing onissues of closure, such as lack of opportunities for reburial, commemoration, and the proper documentation of the dead, the missing, and their surviving families.

Compensation and the general uplift of the affected regionhave, justifiably,been headline issues among victims and civil society.

After a woeful lack of action during Robert Mugabe’s administration, the honeymoon overtures by his successor gave some hope.

- In Full: eighteenth post-cabinet press briefing June 28, 2022

- Unicef supports basic water supply services to 1, 2 million people – report

- Bubi human remains discovery sparks debate

- Bubi human remains discovery sparks debate

Keep Reading

Unfortunately, President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s current Gukurahundi Presidential Outreach Programme is making headlines for its shortfalls, not least being issues around terms set by a perpetrator state, lack of legal framework, the fronting of chiefs as convenors of engagement meetings, and the decision to hold these meetings in camera.

And why is the programme seemingly starting on a blank slate when there are two commissions of inquiry reports that have remained under state embargo since the 1980s?

Is this a mere placebo-effect programme, which is to say, it is a dummy treatment given during drug experimentation?

Unlike the real drug, a placebo does not contain any healing powers, except working through the illusion of the mind.

There are limitations to whatchiefs can achievein such a complexarea of historical human rights abuse.

Let’s take the health effects of Gukurahundi, for instance, how will chiefs grapple with thisvery specialised aspect of genocide violence?

The health effects of Gukurahundi were multifaceted and complex. Holistically dealing with just this one aspect of the genocide would require multidisciplinary health teams — including physicians, epidemiologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and infectious diseases specialists (HIV and Aids), among others, as the examples below suggest

First, there were the obvious physical effects of the wanton military violence: the breaking of limb and bone, the maiming, the bludgeoning — all of which had very real physical harms.

In 1997, the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP), working in collaboration with the Legal Resources Foundation (LRF) produced the Breaking the SilenceReport, the first and last authoritative compilation of the Gukurahundi atrocities by an independent body in pursuit of truth and justice.

Contained in this report are gory details of military ethnic cleansing, which wasmasked as a legitimate counter-insurgency measure against what has been established to have been a minuscule or even a phantom dissident threat.

In one of the hundreds of cases featured in their Report, the CCJP and LRF documented how villagers in the Nyamandlovu/Tsholotsho areas “… had to watch those close to them dying slowly from untreated wounds.”

They had been warned not to seek medical help and could be shot as curfew breakers if they tried. Many others have permanent disabilities and cannot work well in their fields or carry loads anymore” (abridged version, p. 15).

This was a common experience acrossthe greater Matabeleland and Midlands provinces.

In addition to the difficulties experienced in accessing urgent treatment, health service providers in the region were not spared the wrath of the Fifth Brigade.

For example, according to the CCJP/LRF Report, several clinic staff were murdered in Nkayi district in 1987, the very same year of the formal end to the genocide.

Therefore, as far as the physical harms of Gukurahundi are concerned, the evidence is overwhelming, and the bodies of many surviving victims continue to act as the ‘living archives’ of the harmsof the genocide.

Secondly, there is the psychological trauma which has remained untreated.

This occurred on many levels, including witnessing the macabre murders, rape, physical torture, destruction of property and forced relocation.

Victims continue to be traumatised by inconsiderate acts such as the free play and remixing of songs that accompanied the torture, such as Mai VaDhikondo, a Gukurahundi song that should have been banned by now.

Many victims have been suffering in silence, nursingnumerous traumas that can be easily traced back to the Gukurahundi.

But this is not just ordinary silence. It is a ‘noisy silence’ to borrow from Oxford scholar, Jocelyn Alexander. People are speaking, but no one in government is listening.

Over the past few years, some surviving victims have been speaking through various modes such as Zenzele Ndebele’s foresighted video documentary programme, Asakhe Online, with the film I Want My Virginity Back: A Story of Survival & Healing from Rape During Gukurahundi Genocide being one such mode. This speaking is only the beginning, and not the end, of PTSD healing.

Thirdly, when other parts of the country started turning their swords into ploughsharesat the end of the liberation war that ushered independence in 1980, the genocide added to Matabeleland another decade of more intensive disruptionof communal harmony,which is vital for community well-being.

This was worsened by the food embargo introduced in the early months of 1984. The enormous implications of this forced malnutrition in this generally drought-prone region have remained obscure.

In Matabeleland South, where I grew up, at one moment my family survived on wild okra and other wild herbs due to the food embargo.

As part of the embargo, shops were closed, food aid distribution was blocked, and available food provisions were confiscated or destroyed.

Finally, we should consider the wanton rape, which happenedin the context of the emerging HIV and Aids pandemic.

Presently,the Matabeleland regions consistently carry the largest HIV and Aids statistics in Zimbabwe compared to other regions.

A knee-jerk view would blame regional migration and historical proximity to South Africa, considered to be the global epicentre of the pandemic.

However, it is well-known that rape was widely used by the Fifth Brigade troops as a genocidal tool.

Many Gukurahundi children were born during that era. It is therefore common cause that STIs, including HIV and Aids, were spreadquite easily in that cauldron of sexual violence.

In a nutshell, the Gukurahundi genocide was both a health hazard and a risk multiplier. Not only did the affected region miss out on the development dividend of the 1980s, but it also faced what we can call the Gukurahundi Pathocene — an apocalyptic encounter with violence and ill-health!

Against this backdrop, it is easy to see the serious inadequacy of President Mnangagwa’s outreach programme,and people’s well-founded misgivings about it.

Of course, chiefs can,with appropriate training, facilitate aspects of the process. However, given the multifaceted impact of the genocide, the chiefs’ process can only form one workstream, not the whole process.

Health requires its own multidisciplinary workstream. Therefore, instead of wasting time on placebos, we should be focusing onforging a comprehensive programme.

- Dr Ncube grew up in Matabeleland South in the 1980s. He can be contacted at [email protected]