A lasting solution to the Gukurahundi debacle has remained elusive for four decades now, and President Emmerson Mnangagwa has turned to traditional leaders to bring finality to the matter.

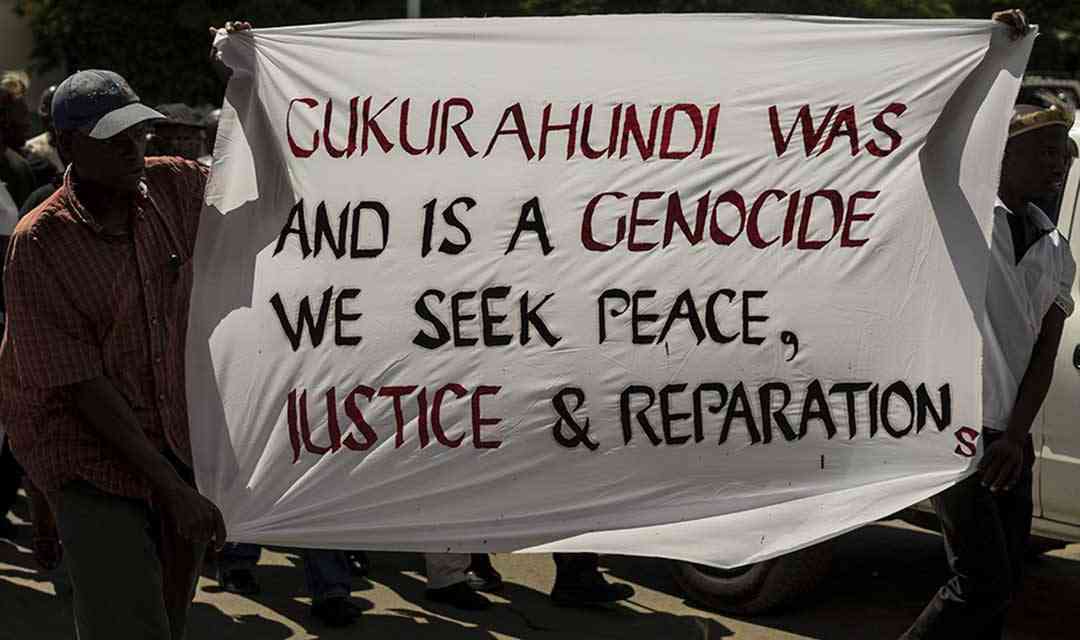

Questions are asked not only about the sincerity of the government but also about the appropriateness and the capacity of the chiefs to address a genocide.

Under normal circumstances, we should be commending the Second Republic’s bold steps in reopening discussions on Gukurahundi and its community engagement outreach, had it not been for its glaring but avoidable limitations.

Unfortunately, this could be yet another missed opportunity to address a dark chapter in the country’s history where we can collectively say never again.

The key question is ‘should we allow this never again moment to be aborted’?

Perhaps it is important to give a brief context to this matter.

All along, the ruling party had stuck to its self-serving denialism that the December 221987 Unity Accord between PF-Zapu and Zanu PF had sealed the matter.

If that be the case, why is Mnangagwa re-opening it? Of course, it is not out of magnanimity but a response to unabating calls for justice.

The voices crying for justice from mass graves, disused mine shafts, riverbeds, toilet pits, caves and burnt huts have refused to be silenced.

By committing to address Gukurahundi the president created the long-awaited opportunity to bring finality to the matter, so we thought.

As if to prove the sceptics right, the outlined chiefs’ process shattered any hope that the matter could ever be resolved under ZanuPF’s rule.

The bombshell that destroyed the last iota of hope was dropped by none other than the deputy president of the Chiefs’ Council, Chief Fortune Charumbira, when addressing the media, when he unconsciously, but revealingly, narrowed the chiefs’ outreach programme to a mop exercise of recording those who might be considered for compensation.

Charumbira harped on the compensation issue, creating a false impression that it is all about cash!

With that attitude, the chiefs’ programme was doomed just days before it even began.

If chiefs go out to the people with this denialist attitude that trivialises the genocide, then their programme shall be deemed flawed on the very basis of insensitivity to pain and trauma by victims.

Charumbira confidently portrayed the national president as benevolent and ready to pay for compensation, further entrenching the official narrative that civilians were mere collateral damage whose losses could be monetized at the discretion of the president.

However, counternarratives allege that this was in fact a genocide and ethnic cleansing exercise targeting Ndebele-speaking people, despite being camouflaged as a counterinsurgency operation.

It would have been wise for the chiefs to approach the matter with open minds and steer clear of the entrenched and unreconcilable positions on whether Gukurahundi was a genocide or not until after gathering public views.

I have argued before that one is unlikely to solve a problem that one cannot define and demonstrate understanding of.

Due to its denialist posture, the chiefs’ process narrows and individualises victimhood to the exclusion of community or collective suffering and trauma.

By denying witnesses to speak out in a community gathering (but in camera), then only individual suffering becomes the target, yet the torture, sexual orgies, rape and mass murders were a public spectacle.

Apart from Charumbira scoring an own goal to the chiefs’ process, there were already other inherent issues that undermined the legitimacy of the outcome.

One being the exclusion of a hard-hit province like the Midlands.

Excluding the Midlands province has been perceived as a deliberate and revisionist strategy to narrow the geographic spread of the Gukurahundi destruction.

It is in the Midlands with both Ndebele-speaking and Shona-speaking communities that gives proof of ethnic targeting and hence evidence of genocide as homesteads of Ndebele-speaking people were torched while those of Shona-speaking members were spared.

Equally excluded are urban areas since they are outside traditional leaders’ areas of jurisdiction.

Yet many survivors who escaped from mass murder fled to Bulawayo for refuge.

Those in Bulawayo saw and experienced much brutality during the curfew and door-to-door searches.

Some were arrested, especially former ZPRA combatants or Zapu leadership, while others were never to be seen again.

All these gruesome things happened in Bulawayo as well as in other urban centres, such as Kwekwe, Hwange, Gwanda and Beitbridge.

In 1983, as a form three schoolboy attending Luveve Secondary School, I saw the fifth brigade soldiers in Bulawayo and witnessed some of their brutality.

They deployed along the railway line, and we could not cross to the nearest school gate but were forced to walk a long distance along the railway track to use the only gate allowed to us.

One late afternoon, we witnessed the soldiers forcing an elderly couple to fight with sticks.

When the woman could not hit her husband forcefully, one soldier took the stick and demonstrated to the woman the type of beating they expected.

She fell down just after with whipping.

As children, we could not help but sob at what we were witnessing.

The old man decided that rather than beat his wife in return, he would shoulder all the cruelty and pain.

It was a sordid sight for us as children whose memory continues to frighten to date.

It is common cause that many traditional leaders themselves were victims of the genocide. How will they feign neutrality to their own pain?

In my home area of Nswazi in the Umzingwane district, the late Chief Howard Mabhena, who was my maternal uncle, was tortured too.

His headman, who once acted as Chief Bhaka, was murdered allegedly by bandits in December 1985.

It would be ironic if not insulting for the reigning Chief Sinqobile Mabhena and Headman Mqwayi Bhaka to ask the Nswazi community to tell of their trauma and pain when they themselves are the most affected.

It is such realities that do not inspire hope in the chiefs’ programme.

The nation wants truth-telling, which can only be achieved if the two sides of the story – that of the victim and the perpetrator – are known.

We do not hear of chiefs summoning perpetrators who remain amnestied. Without the perpetrator feeling any sense of wrong-doing and remorse, then as a country we cannot reach the NEVER AGAIN MOMENT.

*Dr Samukele Hadebe is an academic, author and political activist writing in his personal capacity and can be contacted by email [email protected]