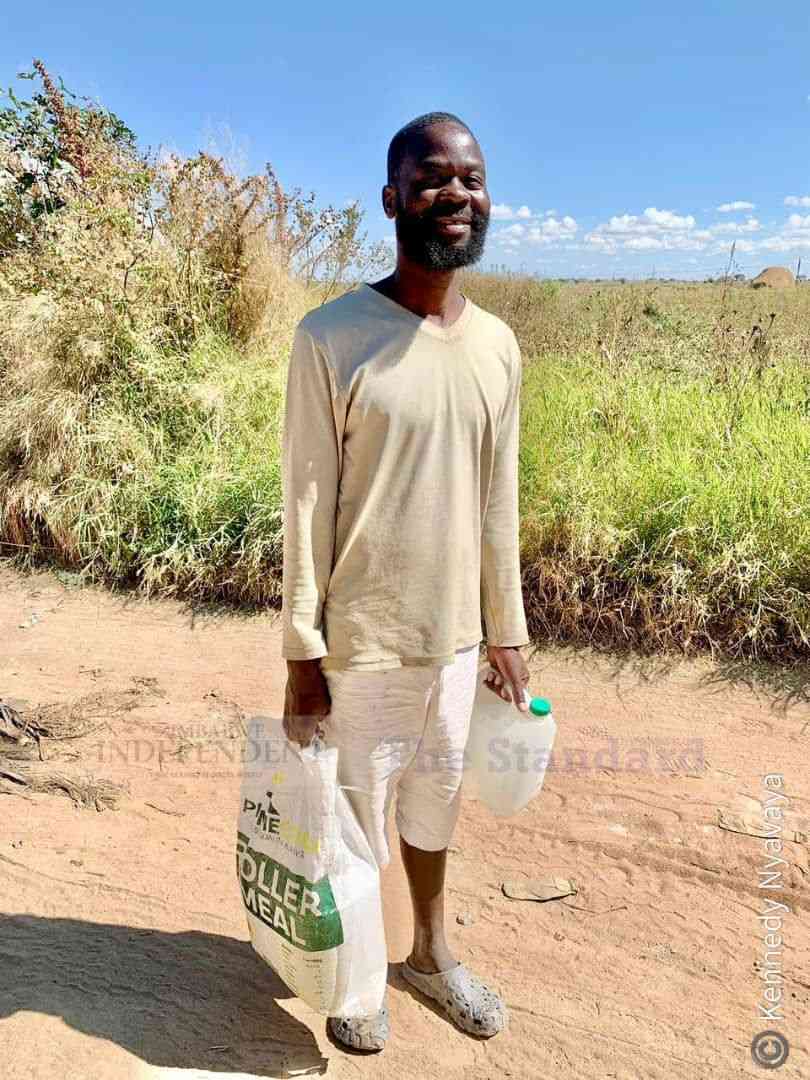

On two-day intervals, Madzibaba Simba (38) and his wife trek for over an hour into the Eastern part of the Cleveland wetland, which sits on the edge of Mabvuku in Harare, to access a basic human right enshrined in section 77 of Zimbabwe’s constitution.

“Every person has the right to— (a) safe, clean and potable water,” reads the document that provides a framework for the country’s governance, human rights, and rule of law.

However, in most parts of Mabvuku, merely getting the life-sustaining liquid is an arduous task while securing it clean and safe to drink can be nothing short of a miracle.

With tap water out of the question as most parts of the populous settlement have gone for over three decades without supply from council, while boreholes are either contaminated or drying up, the resourceful couple has been forced to explore alternative sources in the nearby wetland.

“We come here to fetch water to drink from springs, it is the only place we can find it clean and pure,” the father of four told this publication.

“We used to fetch water at the community borehole but the water there now tastes rusty and we can tell that it is not fit for consumption.”

A wetland is a land area that is saturated with water, either permanently or seasonally, such that it takes on the characteristics of a distinct ecosystem. Among many functions, wetlands play a pivotal role in the water cycle as they recharge underground water by allowing it to sink into the soil, they act as natural purifiers, and reduce high runoff which is a major cause of flooding.

- Entrepreneurship and industrialisation in Zimbabwe (Part 3)

- Entrepreneurship and industrialisation in Zimbabwe (Part 3)

- Mr & Miss Truth22 crowned

- Feature: Aged people haunted by abuse in Zim

Keep Reading

These benefits are in jeopardy at Cleveland owing to continued destructive human activity like sand mining causing the massive disturbance of the wetland.

Heaps of mined sand, scattered ponds with slimy green water and unfilled trenches, all features that echo a story of wanton pillaging and neglect, can be seen as one walks into the wetland.

Ironically, the ecologically sensitive space is a Ramsar site, which means it is a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention — an international treaty signed in 1971 that Zimbabwe is also a party to.

It is also considered “the largest protected natural area in Harare” yet reality on the ground points to the opposite.

“Mabvuku is one of the driest suburbs in Harare because there are some sections that have gone for more than three decades without tap water from council so the dilapidation of important water sources like the Cleveland catchment area have exacerbated the massive water shortages”

“Our main challenge is that of the sand mining which is happening in the Eastern part of this wetland. It has been ongoing and we have been making interventions by engaging the relevant authorities,” Cleveland Action Alliance Trust founding trustee Jimmy Mahachi told a delegation of legislators visiting to see the current state of the wetlands recently.

Part of the Trust’s efforts, says Mahachi, has been “writing to them (authorities)” with the latest being a petition submitted to parliament in May, which has seemingly fallen on deaf ears as no response or acknowledgement has been communicated to date.

Local environmentalists argue that while the country possesses somewhat good laws and policies for the protection of the environment, enforcement on the ground is faltering.

In July, the country hosted a historic COP15 summit on wetlands –an international event towards the protection of ecologically sensitive spaces– and now holds the presidency for the next three years but this is yet to translate to a positive shift in the national environmental conservancy.

“If you have been following up on reports that were made by different stakeholders that included residents associations and civic society of late there have been fresh cases of destruction of wetlands even after COP15…so it is still business as usual,” says Hardlife Mudzingwa.

“There were resolutions that were passed and commitments that were made, but on the ground, the situation is still the same.”

Across the country, the gap between environmental laws and implementation has since been exploited by individuals and corporations who continue to encroach into wetlands for different reasons.

Currently, Environmental Management Agency officials have reported that they are finalising a new wetland mapping exercise but a similar process conducted in 2021 showed that only 17.63% of the country’s remaining wetlands were in pristine conditions, 55.65% moderately degraded while 26.72 % had been severely degraded. Over the years, the ecological damage has gotten worse hindering ordinary citizens from accessing environmental rights engraved in section 73 of the supreme law.

But, the country can take advantage of the current COP15 “momentum on wetlands protection” to make sterner environmental laws and ensure strict adherence according to human rights and environmental lawyer Fiona Illiff.

“I think having a strong push for legislative and policy reforms that really prohibit any development on wetlands would provide more protection.

“We need to move quickly and establish conservancies and nature reserves on wetlands so that they are not seen as empty land waiting for development,” Iliff said, adding that government’s actions ought to be in sync with its rhetoric.

“There are quite a lot of competing interests within government as there is also a strong push for mining and housing developments particularly in Harare which is causing a lot of destruction of wetlands.”

While campaigners continue to lobby for an end to wetland destruction, Simba hopes that reprieve comes soon to save the springs within the Cleveland wetland before they either get contaminated or vanish.

“A lot is happening and if you walk through the wetland, you will find some damaged pipes dug up by sand poachers and we are not sure whether they are for potable water or sewage, for all we know effluent could end up mixing with this spring water that we consider pure and commit to walk the long distance to fetch,” says Simba as the couple takes off with 25 liters of their family’s lifeline for the next 48 hours.