The quest for reparations and compensation for victims of mass atrocities has become an increasingly important aspect of transitional justice and post-conflict reconstruction.

As countries confront the legacies of historical violence, they often draw on both international and regional experiences to shape reparative justice frameworks.

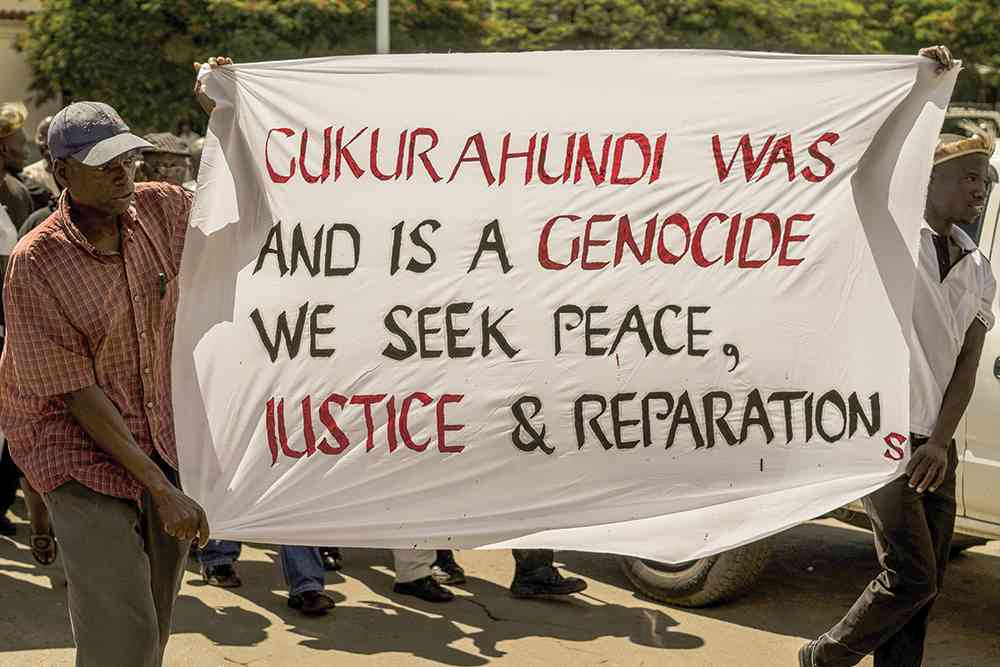

In the context of Zimbabwe, the drafting of a reparations bill for victims of the Gukurahundi atrocities (1983–1987) may present a profound opportunity to heal old wounds and build a just future.

The Gukurahundi period left deep scars across Matabeleland and parts of the Midlands, resulting in loss of life, displacement, and enduring trauma, among others. Addressing these harms requires a process that combines accountability, truth-telling, and tangible redress.

Across Africa, nations such as Rwanda, Namibia, and South Africa have developed distinct yet instructive approaches to reparations and reconciliation.

Rwanda’s post-genocide process emphasized community-based justice through Gacaca courts and symbolic reparations. Namibia’s engagement with Germany on the Herero and Nama genocides foregrounded intergenerational recognition and development-oriented restitution.

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) pioneered a hybrid model of individual and community reparations, balancing symbolic acknowledgment with material support.

By integrating these African experiences with global principles of justice, Zimbabwe can design a reparations framework that is context-sensitive, inclusive, and transformative—one that fosters both healing and national unity.

- Ziyambi’s Gukurahundi remarks revealing

- Giles Mutsekwa was a tough campaigner

- New law answers exhumations and reburials question in Zim

- Abducted tourists remembered

Keep Reading

Reparations for mass atrocities are not merely acts of goodwill; they are obligations grounded in international and regional law.

The United Nations’ Basic Principles on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation affirm victims’ rights to restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition.

Similarly, the African Union’s Transitional Justice Policy emphasises reparations as a cornerstone of post-conflict reconstruction and national healing.

Zimbabwe’s proposed Gukurahundi reparations framework should, therefore, be built upon these principles, ensuring that victims are not treated as passive recipients of state benevolence but as rights-holders entitled to justice and dignity.

Countries that have implemented reparations programs have adopted varied eligibility criteria to determine who qualifies for compensation.

Germany’s post-Holocaust compensation, for instance, required proof of persecution based on race, religion, or politics. In Africa, lessons from Rwanda, Namibia, and South Africa demonstrate that inclusivity and cultural context are key.

Rwanda recognised both direct and indirect victims—women who suffered gender-based violence, children orphaned by genocide, and those deprived of livelihoods.

Namibia’s approach acknowledged descendants of victims as legitimate beneficiaries, recognising the long-term effects of colonial atrocities.

South Africa’s TRC extended eligibility to anyone who suffered politically motivated harm, whether physical, psychological, or economic.

For Zimbabwe, eligibility should encompass those killed or tortured, displaced families, survivors of sexual violence, orphaned children, and communities deprived of land or livelihoods.

Given the destruction of records and the culture of silence induced by fear and trauma, verification processes must be flexible and culturally grounded.

Community testimony and local validation—like Rwanda’s use of traditional mechanisms—can ensure fairness while respecting oral histories and collective memory.

Reparations must explicitly address the gendered and intergenerational impacts of Gukurahundi. Women bore the brunt of sexual violence, forced displacement, and widowhood, yet their voices often remain marginalised.

Youth born in the aftermath of the conflict continue to face social exclusion and economic hardship linked to their parents’ victimisation.

A gender-sensitive approach should provide targeted psychosocial support for survivors of sexual violence, educational scholarships for orphaned children, and economic empowerment initiatives for women-headed households.

Including young people in the reparations dialogue is vital to ensuring intergenerational truth-telling and preventing historical amnesia.

Effective reparations go beyond financial compensation to include symbolic, restorative, and developmental measures.

Germany offered both lump-sum payments and pensions; Austria provided fixed amounts for marginalised victims.

African experiences further highlight that reparations must rebuild communities as well as individuals.

In Rwanda, reparations emphasized community reconstruction, education for orphans, and psychosocial rehabilitation. Namibia’s negotiations with Germany sought collective projects such as land restitution and community development funds.

South Africa’s TRC recommended a blend of individual monetary payments and collective reparations, including scholarships and public memorials.

For Gukurahundi survivors, Zimbabwe could adopt a hybrid model combining financial assistance with social and symbolic measures—healthcare access, trauma counseling, educational support, livelihood restoration, and community infrastructure.

Symbolic gestures such as a national apology, official memorials, memorial site and an annual day of remembrance would complement material compensation, affirming the victims’ dignity and recognition within the nation’s history.

Administrative frameworks

The success of any reparations program depends on credible and transparent administration.

Some countries have created independent agencies to oversee reparations, ensuring accountability and efficiency. African experiences underscore the importance of community involvement and decentralization.

Rwanda’s National Unity and Reconciliation Commission effectively coordinated reconciliation initiatives, while South Africa’s TRC Reparations Committee managed compensation disbursement and policy development.

Namibia’s Ombudsman’s Office and traditional leadership structures also played roles in victim registration and advocacy.

For Zimbabwe, a National Gukurahundi Reparations Commission (NGRC) could serve as the central coordinating body.

It should include representatives from government, civil society, traditional leaders, religious organizations, and victims’ associations.

Local-level committees could mirror Rwanda’s decentralised reconciliation units, ensuring accessibility and trust. A grievance redress system and appeal mechanism would safeguard fairness and transparency.

Funding mechanisms

Financing reparations is a common challenge worldwide.

Germany established a dedicated compensation fund; Rwanda relied on national and international contributions, including community solidarity initiatives such as Umuganda.

Namibia pursued bilateral financial agreements with Germany, while South Africa primarily used domestic fiscal resources to maintain sovereignty over its process.

*This article was written by Sibusisiwe Dube, a public administration student at the African School of Governance in Rwanda, specialising in transitional justice and development policy. Her research focuses on governance reform, post-conflict reconstruction, and participatory policymaking in southern Africa.